Cracking a skill-specific interview, like one for Commitment to Braille Excellence and Advancement, requires understanding the nuances of the role. In this blog, we present the questions you’re most likely to encounter, along with insights into how to answer them effectively. Let’s ensure you’re ready to make a strong impression.

Questions Asked in Commitment to Braille Excellence and Advancement Interview

Q 1. Explain the difference between Grade 1 and Grade 2 Braille.

Grade 1 Braille and Grade 2 Braille are the two main systems for representing English text in Braille. The core difference lies in how they represent words.

Grade 1 Braille is a literal, letter-by-letter transcription. Each letter of the alphabet has its own corresponding Braille cell. Think of it like a one-to-one mapping: ‘A’ is always represented by the same Braille cell, ‘B’ by another, and so on. This makes it very straightforward to learn, but it can be lengthy and inefficient for common words.

Grade 2 Braille uses contractions and short forms. Common words, prefixes, and suffixes are represented by single Braille characters or combinations, speeding up reading and writing. For example, the word ‘and’ might be represented by a single Braille character instead of the six individual Braille letters representing ‘a’, ‘n’, ‘d’. While more efficient, Grade 2 requires learning and memorizing these contractions.

Imagine writing a sentence in shorthand versus writing it out phonetically, letter by letter. Grade 2 Braille is like shorthand – faster and more compact, but requiring more up-front learning.

Q 2. Describe your experience with Braille transcription software.

I have extensive experience with various Braille transcription software packages, including Duxbury Braille and Braille Ready. My proficiency extends beyond basic transcription; I’m comfortable utilizing advanced features like formatting, creating tables, and incorporating mathematical and scientific notations. I’m adept at troubleshooting common software issues and integrating Braille transcription into diverse workflows. For instance, I recently used Duxbury to create a complex Braille textbook incorporating diagrams and mathematical equations, ensuring faithful translation of the original print format. This involved meticulous attention to detail and careful consideration of the software’s capabilities to maintain readability and accessibility.

Q 3. How do you ensure accuracy and consistency in Braille transcription?

Accuracy and consistency are paramount in Braille transcription. My approach involves a multi-layered strategy.

Careful Transcription: I meticulously follow the Braille code, ensuring every character and punctuation mark is accurately represented. I regularly consult authoritative Braille style guides.

Software Validation: I leverage software features to identify potential errors, such as misspellings or incorrect contractions. Duxbury, for instance, offers spell-checking functionalities specific to Braille.

Proofreading and Editing: A rigorous proofreading process is crucial. This typically involves independent review by another qualified transcriber to catch errors missed during the initial transcription phase. I actively use a combination of software-based checking and manual review.

Adherence to Standards: I strictly adhere to the latest Braille standards and style guides, ensuring consistency in formatting, punctuation, and the use of contractions. This ensures the transcribed material meets international standards for accessibility.

This multifaceted approach minimizes errors and ensures the final Braille product is accurate and easily readable.

Q 4. What are the common challenges faced in Braille transcription, and how do you overcome them?

Braille transcription presents several challenges.

Complex Formatting: Handling complex formatting, such as tables, equations, and diagrams, requires specialized software and skill to maintain the structural integrity of the document.

Inconsistent Source Material: Poorly formatted or inconsistently styled source material can introduce ambiguities and make accurate transcription challenging. Clear communication with the source material provider is essential.

Technical Symbols: Representing technical symbols and notations requires knowledge beyond basic Braille. For example, transcribing mathematical symbols or musical notation necessitates specialized Braille codes.

I overcome these challenges by:

Utilizing Appropriate Software: Selecting and utilizing appropriate software with advanced features for complex formats is key.

Clear Communication: Establishing clear communication with clients to resolve ambiguities and ensure a clear understanding of the source material.

Continuous Learning: Staying current with advancements in Braille technology and Braille codes for specialized areas.

Q 5. Explain your understanding of Braille code and its variations.

Braille is a tactile writing system using raised dots to represent letters, numbers, punctuation, and other symbols. The basic unit is the Braille cell, which consists of six dots arranged in a rectangular pattern. Different combinations of raised dots represent different characters.

English Braille is based on a six-dot code, but there are variations and regional differences.

Grade 1 and Grade 2: As mentioned earlier, Grade 1 uses a literal, letter-by-letter representation, while Grade 2 employs contractions and short forms for efficiency.

Nemeth Braille: This code is specifically designed for mathematical and scientific notations.

Computer Braille: This code provides representations for computer commands and symbols.

Foreign Language Braille: Different languages utilize adapted Braille codes to accommodate their unique alphabets and linguistic structures.

Understanding these variations is critical for accurate and appropriate transcription, ensuring that the Braille document is accessible and understandable to the intended reader, regardless of their background or language.

Q 6. Describe your experience with proofreading and editing Braille documents.

My experience in proofreading and editing Braille documents involves a detailed, systematic approach. I’m not just looking for spelling or grammatical errors; I’m checking the overall structural integrity, ensuring the document flows logically and maintains the integrity of the original content in tactile format.

Software Assisted Checks: I utilize software’s built-in features for spell-checking and identifying formatting inconsistencies.

Manual Review: I conduct a thorough manual review, reading the Braille document with my fingers, paying close attention to the flow, punctuation, and spacing.

Comparison with Source Material: A critical step involves careful comparison with the source document to ensure the Braille version accurately reflects the original content and formatting.

Through this meticulous process, I ensure the Braille document is not only free of errors but also easily readable and understandable.

Q 7. How do you ensure the accessibility of Braille materials for different users?

Ensuring the accessibility of Braille materials for different users involves understanding their diverse needs and tailoring the transcription accordingly.

Grade of Braille: Considering the user’s Braille reading proficiency: beginners might require Grade 1, while more advanced readers may benefit from the efficiency of Grade 2.

Font Size and Spacing: Adjusting the font size and spacing between lines to optimize readability for users with visual impairments or dexterity limitations. Larger print size and wider spacing improve readability.

Formatting: Employing clear and consistent formatting to improve navigation and understanding, particularly for complex documents such as textbooks or legal documents.

Supplementary Materials: Providing supplementary materials, such as audio descriptions or large-print versions, to complement the Braille document and enhance comprehension for users who might benefit from a multimodal approach.

By understanding and accommodating diverse needs, I strive to create Braille materials that are truly accessible to everyone.

Q 8. What are some common errors in Braille transcription and how to avoid them?

Common errors in Braille transcription stem from a misunderstanding of Braille rules, inconsistencies in formatting, and a lack of attention to detail. These can range from simple spacing errors to misinterpretations of complex mathematical or scientific notations.

Incorrect Contractions and Abbreviations: Using incorrect or inappropriate contractions can significantly alter the meaning of a text. For example, using the wrong contraction for ‘ough’ could change the entire word.

Improper Punctuation and Spacing: Braille punctuation and spacing are crucial for readability. Incorrect spacing between words or sentences, or misplaced punctuation marks, can create confusion for the reader. Imagine the difference between “Hello, world!” and “Hello world!” in Braille – the comma changes everything.

Errors in Mathematical or Scientific Notation: Transcribing complex mathematical equations, chemical formulas, or musical notation requires a deep understanding of the specific Braille codes involved. A small error in a formula could render it completely unintelligible.

Inconsistencies in Formatting: Maintaining consistent formatting throughout a document—including headings, tables, and lists—is crucial. Inconsistent use of capitalization or formatting codes leads to a disjointed and difficult-to-read text.

Avoiding these errors involves:

Thorough training: A strong foundation in Braille code and transcription rules is essential.

Proofreading: Multiple proofreads, preferably by different transcribers, are critical. This process mirrors the traditional typesetting methods of multiple checks.

Use of Braille transcription software: Utilizing specialized software can help catch many common errors. But, it’s still crucial to proofread thoroughly, software is not perfect.

Reference materials: Always keep authoritative Braille code and formatting guides close at hand. Familiarizing yourself with common pitfalls aids accuracy.

Q 9. What are your strategies for maintaining quality control in Braille production?

Maintaining quality control in Braille production is paramount. It ensures accuracy, consistency, and accessibility for visually impaired readers. My strategies involve a multi-layered approach:

Multiple Proofreaders: Employing at least two independent proofreaders ensures that errors are caught. Each proofreader should follow a standard checklist to ensure comprehensive review.

Use of Quality Control Checklists: Detailed checklists ensure all aspects of the transcription are verified—from proper formatting to accurate Braille codes and punctuation.

Regular Training and Updates: Keeping the transcription team updated on the latest Braille standards, guidelines, and technology is crucial. This ensures consistency and adherence to best practices.

Software-Assisted Quality Checks: Utilizing software designed for Braille transcription can help identify potential errors, although manual proofreading remains essential.

Blind Peer Review: A final check by a blind individual adds an extra layer of quality assurance, ensuring the document is truly accessible and easy to read for the intended user.

Document Comparison: Where feasible, compare the Braille document with its print counterpart to verify accuracy.

These steps create a robust system which is constantly evaluated and improved, ensuring consistent production of high-quality Braille.

Q 10. How do you handle complex formatting requirements in Braille documents?

Handling complex formatting in Braille documents requires a thorough understanding of Braille codes and conventions for tables, lists, mathematical equations, and other specialized elements. It’s like translating a language – you have to understand both the source and the target.

Tables: Braille uses specific codes to represent tables, including cell boundaries and column/row alignment. Understanding these codes is essential to correctly representing tabular data.

Lists: Bulleted and numbered lists are indicated using specific Braille indicators to provide clear structure. Incorrect use can render the list confusing.

Mathematical and Scientific Notation: Specialized codes exist for mathematical symbols, equations, and scientific notations. Accuracy is paramount; a misplaced symbol can alter an entire equation.

Headings and Subheadings: Different levels of headings are marked in Braille using appropriate indicators to enhance the document’s structure.

Footnotes and Endnotes: Braille conventions exist for handling footnotes and endnotes, ensuring that these supplementary elements are linked appropriately.

To address these formatting complexities, I rely on a combination of expertise in Braille codes, specialized software, and meticulous attention to detail. It’s a process that requires thorough planning and understanding of the nuances of Braille formatting to ensure the final document is not only accurate but also accessible and easy to navigate.

Q 11. Describe your experience with different Braille embossers and printers.

My experience encompasses a range of Braille embossers and printers, both manual and electronic. I’m familiar with various models from different manufacturers, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

Manual Embossers: These provide a hands-on approach, offering excellent control over the embossing process. However, they are time-consuming for large volumes of work.

Electronic Embossers: These devices offer significant speed advantages, producing high-quality Braille much faster than manual embossers. They can also often handle complex formatting with ease. Examples include the Freedom Scientific Focus series and the Thiel embossers.

Braille Printers: While not strictly embossers, printers capable of producing Braille output allow for faster throughput in high-volume scenarios. These require careful paper selection and can be more prone to jamming than dedicated embossers.

My experience spans troubleshooting various machine malfunctions, optimizing printer settings for different paper types, and maintaining consistent quality across different devices. Understanding the nuances of each device allows for efficient and effective Braille production.

Q 12. What are the ethical considerations related to Braille transcription?

Ethical considerations in Braille transcription center around accuracy, accessibility, and the rights of the visually impaired reader. The final product must be of the highest quality, without compromise.

Accuracy: Errors can have significant consequences, leading to misinterpretations or a lack of comprehension. Maintaining accuracy is not just a professional obligation but an ethical one.

Timeliness: Delays in producing Braille materials can deprive visually impaired individuals of access to information. Meeting deadlines is an important ethical aspect of this profession.

Confidentiality: Handling sensitive information requires adherence to strict confidentiality guidelines, protecting the privacy of the reader.

Accessibility: Ensuring that the Braille material is fully accessible, including proper formatting and adherence to standards, is crucial. Failing to do so limits accessibility and violates the ethical principles of inclusion.

Copyright: Respecting copyright laws and obtaining necessary permissions when transcribing copyrighted material is non-negotiable.

Ethical practice in Braille transcription demands not only proficiency but also a deep commitment to serving the needs of the visually impaired community with integrity and responsibility.

Q 13. How familiar are you with the latest Braille standards and guidelines?

I am very familiar with the latest Braille standards and guidelines, including those published by organizations such as the Braille Authority of North America (BANA) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). These standards dictate crucial aspects of Braille transcription, ensuring consistency and accessibility across different regions and applications.

My knowledge extends to:

Grade 1 and Grade 2 Braille: I understand the differences between these two systems and can accurately apply the appropriate system based on the specific requirements of the document. Grade 1 utilizes a letter-by-letter system while Grade 2 uses contractions.

Nemeth Code for Mathematics and Science: I have proficiency in this specialized Braille code, ensuring accurate transcription of mathematical and scientific notations.

Unified English Braille (UEB): I’m up to date on the latest developments and nuances of UEB, understanding its implications for consistency and accessibility. UEB is the most widely used standardized Braille system.

Literary Braille: I can apply the standards for literary Braille, paying attention to formatting conventions and textual elements.

Staying current with these standards is an ongoing process, requiring continuous learning and engagement with the Braille community.

Q 14. How do you stay updated on advancements in Braille technology and methods?

Staying updated on advancements in Braille technology and methods is essential for maintaining proficiency in this field. My approach is multifaceted:

Professional Organizations: I actively participate in and follow the publications of organizations like BANA, and other national and international Braille organizations. This gives me exposure to cutting-edge developments and best practices.

Conferences and Workshops: Attending conferences and workshops dedicated to Braille and assistive technologies allows for direct engagement with experts and access to the latest innovations.

Professional Journals and Publications: I regularly read relevant professional journals and publications to stay abreast of new research, methodologies, and technological advancements.

Online Resources and Communities: Engaging with online forums and communities dedicated to Braille and accessibility helps me learn from the experiences of others and keep my finger on the pulse of the field.

Software Updates: I diligently update my Braille transcription software to benefit from bug fixes, new features, and improvements to the software’s capacity to deal with increasingly complex requirements.

This ongoing commitment to professional development ensures that my skills and knowledge remain relevant and up-to-date, allowing me to provide the highest quality Braille services.

Q 15. Explain your understanding of Universal Design and its application to Braille materials.

Universal Design is the practice of creating products and environments that are usable by people of all abilities, including those with visual impairments. Applied to Braille materials, it means designing Braille documents and resources that are accessible not just to proficient Braille readers, but also to those with varying levels of Braille literacy, and even those who might use Braille alongside other assistive technologies. This includes thoughtful consideration of layout, font size (in the case of combined print-Braille), the use of clear and concise language, and the inclusion of supplementary audio or other alternative formats.

For instance, a universally designed Braille textbook might incorporate illustrations and tactile graphics alongside the Braille text, providing multiple access points to the information. It could also include an audio version, accessible via a QR code, enabling readers with differing preferences to engage with the material. The layout itself would be carefully structured for easy navigation and comprehension. Large print alongside Braille could cater to individuals with low vision.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Describe your experience working with individuals who are blind or visually impaired.

I’ve had extensive experience working with individuals who are blind or visually impaired across various settings, including educational institutions, libraries, and publishing houses. This has ranged from assisting students in navigating their academic work to collaborating with authors on the adaptation of their published works into accessible Braille formats. I’ve also worked closely with Braille transcribers, editors, and proofreaders, and regularly attend conferences and workshops focusing on accessible content creation.

One particularly memorable experience involved a high school student struggling with complex scientific diagrams. We collaborated to create tactile graphics that represented the 3D structures accurately, allowing her to understand and interact with the material. Seeing her comprehension grow through the use of these adapted resources was incredibly rewarding.

Q 17. How do you adapt your communication style to meet the needs of individuals with different levels of Braille literacy?

Adapting my communication style to different levels of Braille literacy is crucial. With beginners, I use simple language, focus on core concepts, and incorporate visual aids (if appropriate) alongside Braille. I might offer supplementary audio descriptions or explanations. For proficient Braille readers, I can discuss more complex topics and use technical terminology without simplification. I always gauge their comprehension and adjust accordingly. I find that active listening and respectful questioning are key to ensuring successful communication.

Imagine explaining a complex mathematical equation. For a beginner, I’d focus on explaining each step individually, using simplified language. For someone proficient in Braille and mathematics, I would discuss the underlying principles and potential applications without such simplification. This includes paying close attention to tactile feedback and response to any queries.

Q 18. How would you approach a project involving the transcription of a complex mathematical text into Braille?

Transcribing a complex mathematical text into Braille requires specialized knowledge and tools. My approach would involve a multi-step process:

- Assessment: First, I would carefully review the mathematical text to identify the level of complexity and the symbols used. This includes understanding any specialized notations.

- Selection of Braille Code: The appropriate Braille code (e.g., Nemeth Code for mathematics) would be chosen based on the content’s needs.

- Transcription: I would meticulously transcribe the text using specialized Braille software and ensuring adherence to the relevant Braille code’s conventions. Mathematical symbols would be accurately represented using the appropriate Braille codes and tactile graphic representations.

- Review and Quality Assurance: Rigorous proofreading would follow the transcription, including checks for accuracy, consistency, and adherence to Braille standards. Ideally, this would involve a second professional to verify the transcription.

- Format and Production: The transcribed document would be formatted appropriately for Braille production, ensuring the layout is legible and accessible. This might involve the use of a Braille embosser or digital Braille display.

Throughout the process, close communication with the end-user would be maintained to ensure the final product meets their needs.

Q 19. What is your experience with creating Braille tactile graphics?

Creating Braille tactile graphics requires a deep understanding of both Braille and graphic design principles. It’s not just about translating a visual image into tactile dots; it’s about conveying the meaning and information effectively through touch. I have experience using various methods and tools, including specialized software and tactile drawing techniques to create representations for maps, diagrams, and charts. This involves careful consideration of line weight, texture, and the use of raised lines to create depth and dimension.

For example, creating a tactile map involves deciding on the level of detail, the appropriate scale, and the most effective way to represent landmarks and features using raised lines and textures, so that a blind individual can trace the route or understand the overall layout of an area.

Q 20. Explain your experience with adapting existing materials into Braille formats.

Adapting existing materials into Braille formats necessitates a thorough understanding of both the original material and Braille standards. My approach begins with a careful review of the content, identifying any challenges for Braille translation. I would then determine the appropriate Braille code and create a structured translation that accurately conveys the meaning without compromising readability or accessibility. This includes considerations for text size, layout, and the appropriate use of additional features such as tactile graphics or audio descriptions.

Recently, I adapted a children’s storybook. The original had vibrant illustrations. We translated the story into Braille and created corresponding tactile graphics to represent key scenes and characters. The result was a fully accessible version that maintained the original’s charm and storytelling.

Q 21. Describe a situation where you had to troubleshoot a problem related to Braille production or technology.

During a project involving the transcription of a complex scientific paper, we encountered an issue with a specific mathematical symbol not readily available in our Braille software. This symbol was crucial for conveying the paper’s central concept. To solve this, I researched the Nemeth Braille Code extensively, finding alternative ways to represent the symbol using a combination of existing characters, ensuring accuracy and adherence to the code’s standards. We then meticulously tested this solution in the software and ensured the output met our accessibility goals.

This experience underscored the importance of thorough knowledge of the Braille code and the ability to adapt creatively when facing technical challenges. It also highlighted the value of collaboration and careful testing of solutions before final production.

Q 22. How familiar are you with the different types of Braille displays and their functionalities?

Braille displays are essential assistive technologies for visually impaired individuals, allowing them to read and write Braille. They come in various forms, each with its unique functionalities. The most common types include refreshable Braille displays and static Braille displays.

Refreshable Braille displays: These displays use pins that raise and lower to form Braille characters. They are dynamic, meaning the content displayed can change quickly, mirroring the text on a computer screen. Features vary widely, including cell size, number of cells (characters displayed simultaneously), and connectivity options (USB, Bluetooth). For example, a Focus 40 Braille display offers 40 cells, whereas a smaller, more portable device might only offer 20. The added cells allow for a wider reading experience.

Static Braille displays: These displays usually consist of a fixed number of Braille cells and are often simpler and more affordable than refreshable displays. They are primarily used for specific purposes, such as displaying simple menus or labels. A common example is a Braille label maker that uses a static display to confirm the text being embossed.

Braille notetakers: These devices combine a refreshable Braille display with powerful note-taking and organizational features. They allow users to create, edit, and organize documents, much like a laptop, but with the added benefit of a tactile reading experience. They often incorporate features such as text-to-speech and speech-to-text capabilities.

Understanding the nuances of these different types is crucial for selecting the right display for a user’s specific needs and abilities. Factors to consider include the user’s reading speed, the type of tasks they perform, and their budget.

Q 23. How would you approach teaching Braille to a new student?

Teaching Braille effectively requires patience, a structured approach, and a deep understanding of the tactile learning process. I would begin by introducing the Braille alphabet, emphasizing the six-dot cell as the fundamental building block. I would start with the most common letters, focusing on their tactile shapes and their corresponding printed letters. I would use a combination of methods:

Tactile exploration: Students will actively trace the dots of each Braille character using their fingertips. It’s crucial they feel the dots’ placement and the spacing between them. This kinesthetic approach is key to memorization.

Repetition and practice: Regular practice is essential. We would start with simple words and progress to more complex sentences. I’d use flashcards, tactile games, and even Braille writing practice to consolidate learning.

Positive reinforcement: Celebrating small victories and encouraging the student boosts confidence. The learning curve can be challenging; a supportive environment fosters persistence.

Technology integration: As the student progresses, I would introduce Braille writing tools and refreshable Braille displays, making the learning process more engaging and efficient.

Regular assessments and adjustments to the teaching strategy based on student progress are vital to ensure effective learning.

Q 24. How do you use assistive technologies to improve the efficiency of Braille production?

Assistive technologies significantly enhance Braille production efficiency. I’ve extensively used software like Duxbury Braille Translator and Thunder, which convert digital text into Braille. These programs allow for formatting, including the incorporation of literary elements like italics and bold text. Beyond the translation itself, assistive technologies streamline the process in several ways:

Text-to-Braille conversion: Software automatically translates digital text into Braille, saving significant time and effort compared to manual transcription.

Braille embossers: These machines, often connected to computers, translate the digital Braille code into physical Braille output, allowing for the production of high-quality Braille materials.

Braille editors: Specialized software allows for editing Braille documents directly, providing a more intuitive workflow compared to working solely with sighted-accessible text.

OCR (Optical Character Recognition): For converting existing printed documents into digital text before translation to Braille, OCR software plays a crucial role in digitizing documents and making them accessible.

By effectively integrating these technologies, I can produce high-quality Braille materials efficiently, meeting the needs of visually impaired individuals promptly.

Q 25. What is your experience with different Braille code tables and their applications?

Different Braille code tables exist to represent various languages and symbols. The most commonly used is Grade 2 English Braille, which uses contractions and abbreviations to shorten common letter combinations, making reading faster. Grade 1 Braille uses a one-to-one correspondence between printed characters and Braille characters. I have experience with these, as well as other specialized code tables like those used for music notation or mathematical symbols. Understanding these differences is critical for ensuring accurate and consistent Braille production. For example, the Braille code for ‘ch’ in English Grade 2 Braille is a single character, whereas in Grade 1 it would be two individual characters, ‘c’ and ‘h’. This knowledge directly impacts efficiency and accuracy in Braille translation.

Q 26. How would you handle a situation where a deadline for a Braille project is compromised?

Compromised deadlines necessitate immediate action and effective communication. My approach would be systematic:

Assessment: I’d first pinpoint the cause of the delay—is it a technical issue, a resource constraint, or an unforeseen complexity in the material?

Prioritization: If the entire project can’t be completed on time, I’d prioritize the most crucial sections, ensuring the most essential information is available to the user by the deadline.

Resource allocation: If possible, I’d explore options for additional resources, such as collaborating with other Braille transcribers or using more efficient technologies.

Communication: Open and transparent communication with stakeholders is vital. I’d explain the situation, outlining the revised timeline and the measures taken to mitigate further delays.

Post-mortem: Once the project is complete, I’d conduct a post-mortem analysis to identify the root causes of the delay and implement preventative measures for future projects.

Proactive planning and risk assessment can significantly minimize the likelihood of such situations in the first place.

Q 27. What are your strategies for collaborating effectively with other professionals in creating accessible Braille materials?

Collaboration is crucial in creating accessible Braille materials. Effective collaboration involves clear communication, shared understanding, and mutual respect. My strategy involves:

Defining roles and responsibilities: Clearly outlining each team member’s role prevents duplication of effort and ensures everyone is accountable.

Regular communication: Frequent check-ins, both in person and virtually, using tools like email and project management software, keep everyone informed and allows for prompt resolution of any issues.

Shared document access: Using cloud-based platforms for document sharing allows all team members to access and work on the same files simultaneously.

Quality control: Implementing a rigorous quality control process ensures accuracy and consistency throughout the Braille production process.

Working collaboratively, we ensure the final product meets the highest standards of accessibility and quality.

Q 28. Describe your experience with creating and maintaining a Braille library or collection.

While I haven’t directly managed a Braille library, my experience involves working with extensive Braille collections and organizing Braille materials for educational and personal use. This includes cataloging, classifying, and maintaining the integrity of Braille books and documents. A well-organized Braille collection requires a systematic approach:

Cataloging: Assigning unique identifiers to each Braille item, along with metadata (author, title, publication date) for easy retrieval.

Classification: Organizing the collection using a logical system based on subject matter or Dewey Decimal Classification for easy browsing and retrieval.

Storage: Employing appropriate storage solutions that protect the Braille materials from damage (e.g., acid-free folders, proper shelving).

Maintenance: Regular inspection of the collection to identify and address any damage, ensuring the long-term preservation of the materials.

Creating and maintaining such a collection necessitates careful planning, attention to detail, and a deep understanding of Braille materials’ unique handling requirements. It’s akin to managing any library, but with an added emphasis on the fragility and specific care needed for Braille.

Key Topics to Learn for Commitment to Braille Excellence and Advancement Interview

- The History and Evolution of Braille: Understanding the historical context and ongoing advancements in Braille technology and literacy.

- Braille Transcription Methods and Standards: Mastering the techniques and rules for accurate and efficient Braille transcription, including literary and mathematical Braille.

- Assistive Technology for Braille Users: Familiarity with various assistive technologies, such as Braille displays, refreshable Braille displays, and Braille notetakers, and their applications.

- Inclusive Design Principles for Braille Materials: Understanding how to create accessible and user-friendly Braille materials that meet the needs of diverse learners.

- Teaching and Training Methods for Braille Literacy: Exploring effective pedagogical approaches for teaching Braille to individuals of all ages and abilities.

- Advocacy and Outreach for Braille Literacy: Understanding the importance of promoting Braille literacy and advocating for the rights of blind and visually impaired individuals.

- Quality Assurance and Error Detection in Braille: Developing skills in proofreading and identifying errors in Braille documents to ensure accuracy and readability.

- Current Trends and Future Directions in Braille Technology: Staying abreast of the latest advancements and innovations in Braille technology and its applications.

- Ethical Considerations in Braille Production and Accessibility: Understanding the ethical implications of Braille production and the importance of ensuring equitable access to information for all.

- Problem-Solving and Troubleshooting in Braille Production: Developing practical problem-solving skills related to challenges encountered during Braille transcription and production.

Next Steps

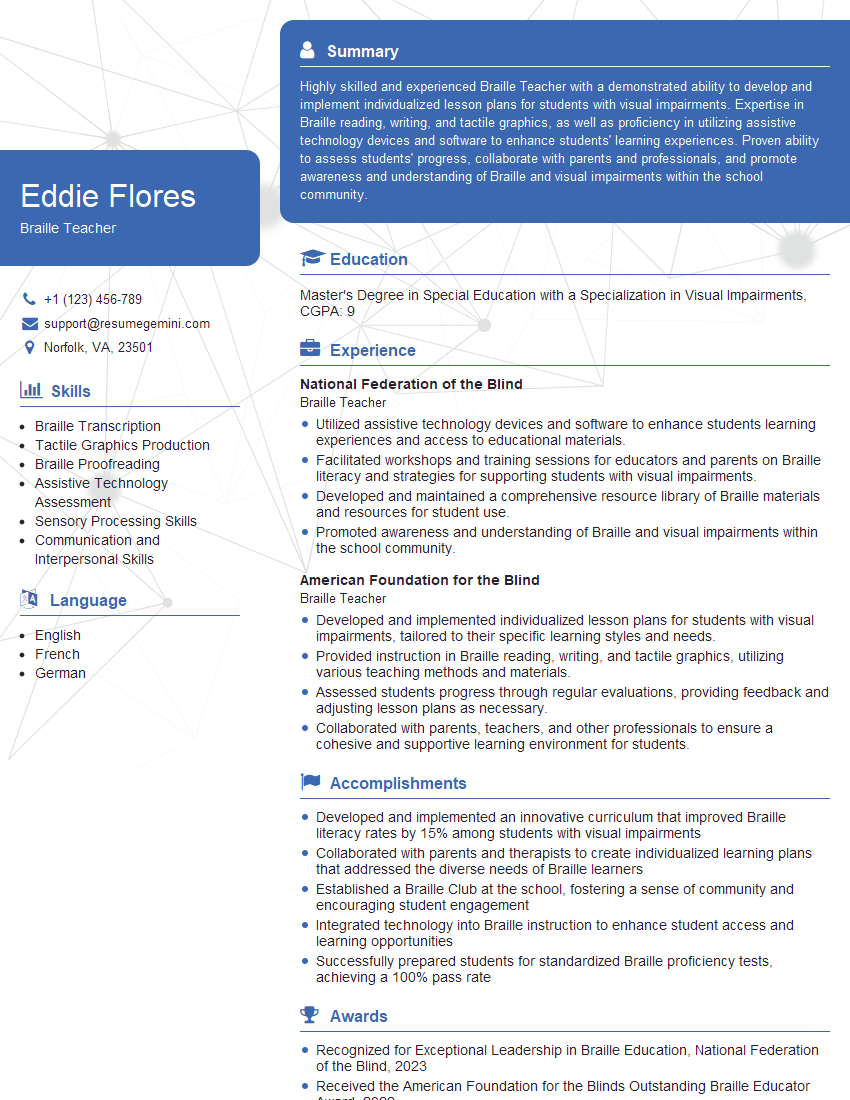

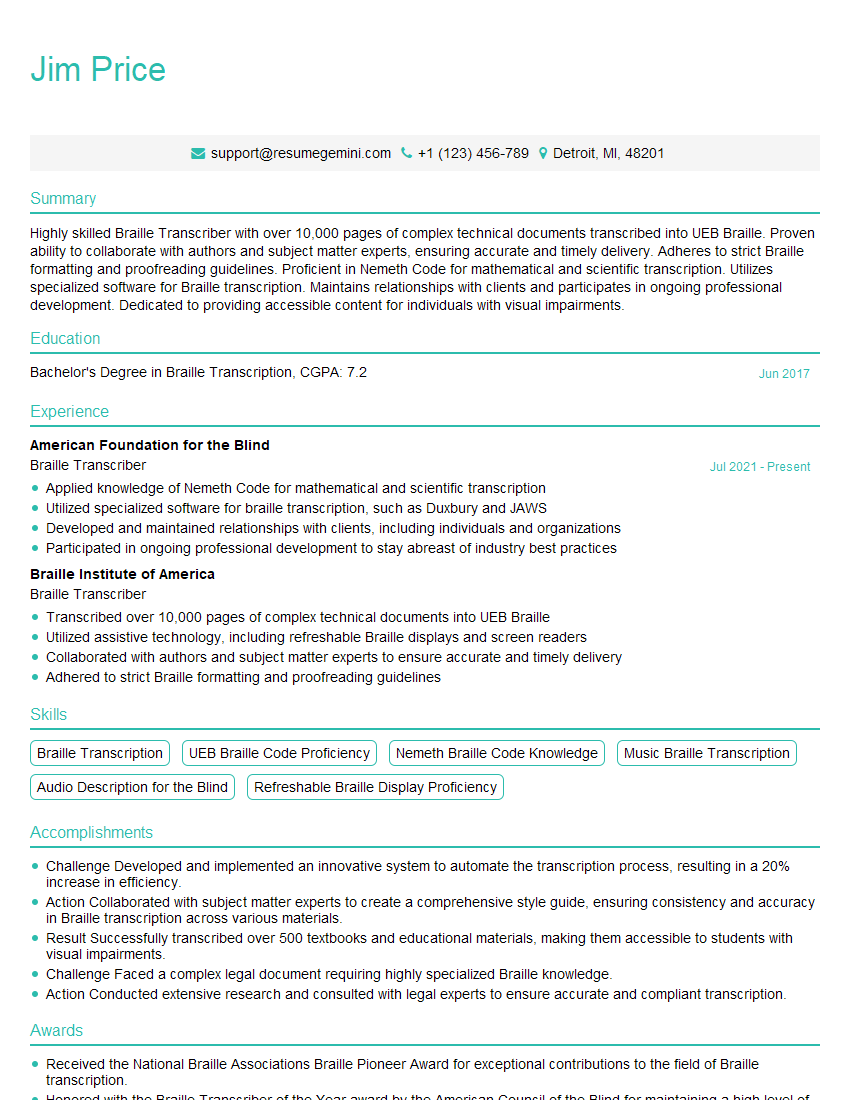

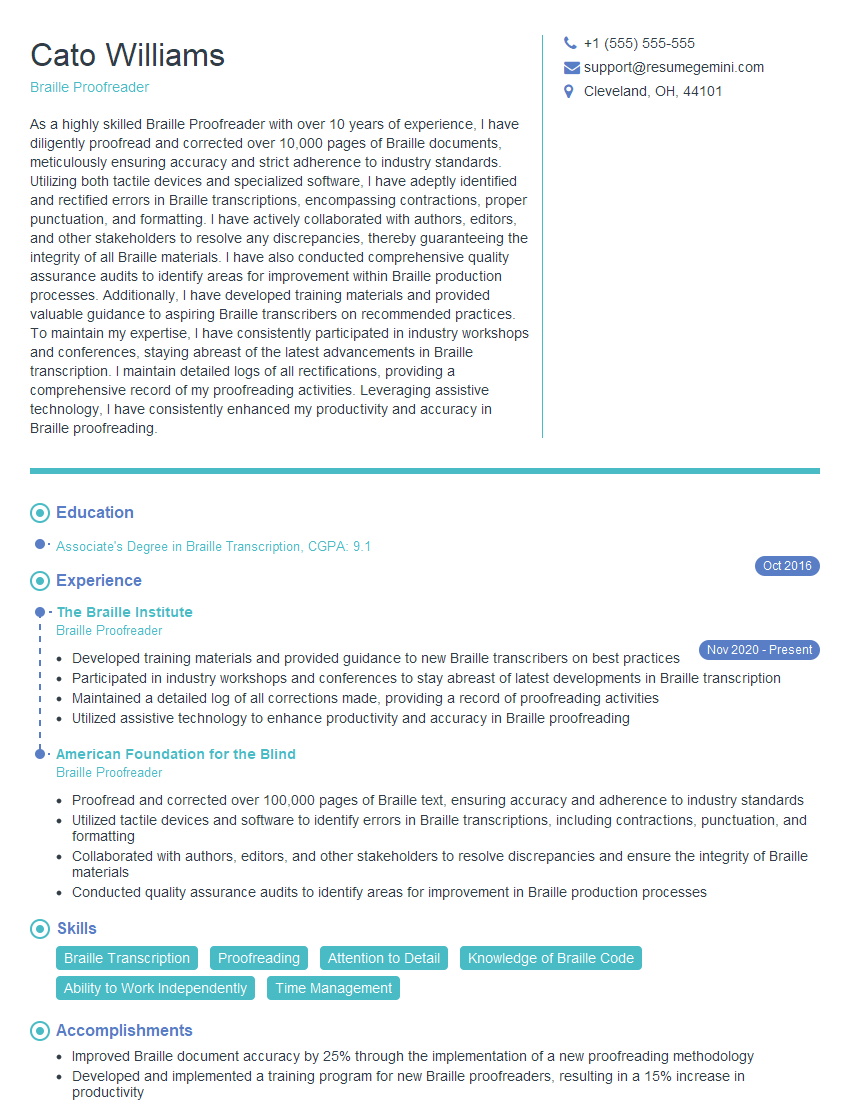

Mastering the concepts related to Commitment to Braille Excellence and Advancement is crucial for career advancement in this rewarding field. A strong understanding of these areas will significantly enhance your interview performance and demonstrate your dedication to promoting Braille literacy. To increase your job prospects, focus on crafting an ATS-friendly resume that highlights your relevant skills and experience. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource that can help you build a professional and impactful resume. Examples of resumes tailored to Commitment to Braille Excellence and Advancement are available to help guide your creation process.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO