Are you ready to stand out in your next interview? Understanding and preparing for Temporal Analysis interview questions is a game-changer. In this blog, we’ve compiled key questions and expert advice to help you showcase your skills with confidence and precision. Let’s get started on your journey to acing the interview.

Questions Asked in Temporal Analysis Interview

Q 1. Explain the difference between stationary and non-stationary time series.

A stationary time series has statistical properties—like mean, variance, and autocorrelation—that remain constant over time. Imagine a perfectly balanced spinning top; its wobble might be consistent, but its overall behavior doesn’t change fundamentally. In contrast, a non-stationary time series exhibits changes in these properties over time. Think of a rocket launch; its velocity drastically changes throughout the process. Many real-world time series, such as stock prices or temperature readings, are non-stationary, exhibiting trends and seasonality that make their statistical properties fluctuate.

Key Differences:

- Stationarity: Constant mean, variance, and autocorrelation.

- Non-Stationarity: Fluctuating mean, variance, and/or autocorrelation. This often manifests as trends (a consistent upward or downward movement) or seasonality (repeating patterns within a fixed period).

Example: Daily sales of an ice cream shop would likely be non-stationary due to seasonal variations (higher sales in summer) and potential trends (growth or decline in overall business).

Q 2. Describe various methods for handling missing data in time series.

Handling missing data in time series requires careful consideration to avoid introducing bias. Several methods exist, each with its strengths and weaknesses:

- Deletion: Simply removing rows with missing values. This is only suitable if the amount of missing data is negligible and randomly distributed; otherwise, it can lead to significant information loss and bias.

- Mean/Median Imputation: Replacing missing values with the mean or median of the entire series or a subset (e.g., the mean of values from the same day of the week). Simple but can smooth out important variations.

- Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF): Imputing missing values with the last observed value. Suitable only if data changes slowly.

- Linear Interpolation: Estimating missing values by linearly interpolating between adjacent non-missing values. This works well for smoothly changing data but can be inaccurate with abrupt changes.

- Spline Interpolation: A more sophisticated interpolation method that uses piecewise polynomials to fit the data. More flexible than linear interpolation but requires more computational effort.

- Model-Based Imputation: Using a predictive model (e.g., ARIMA, Prophet) to forecast missing values based on the observed data. This is generally the most accurate method, but it requires careful model selection and validation.

Choosing a Method: The best method depends on the nature of the data, the amount of missing data, and the goals of the analysis. Always justify your choice and acknowledge potential limitations.

Q 3. What are the assumptions of ARIMA modeling?

ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) models make several key assumptions:

- Stationarity: The time series (after differencing, if necessary) should be stationary. This means its statistical properties (mean, variance, autocorrelation) should be constant over time. We often need to transform non-stationary series using differencing.

- No autocorrelation in the residuals: After fitting the ARIMA model, the residuals (the differences between the actual and predicted values) should not exhibit significant autocorrelation. This indicates that the model has captured the main patterns in the data.

- Normality of residuals: The residuals should be approximately normally distributed. This assumption ensures the validity of statistical tests and confidence intervals used to assess the model’s accuracy.

- Constant variance of residuals (homoscedasticity): The variance of the residuals should be constant over time. This means the model’s predictive accuracy should be consistent across the entire time series.

- Linearity: The relationship between the current value and past values should be linear. Although some non-linear transformations might help (e.g., Box-Cox), strongly non-linear relationships are problematic for ARIMA.

Violations of these assumptions can lead to inaccurate forecasts and unreliable inferences. Diagnostic checks, such as autocorrelation plots and normality tests, are crucial to assess the model’s adequacy.

Q 4. How do you identify seasonality in a time series?

Identifying seasonality involves detecting repeating patterns within a fixed period in your time series data. Several methods can be used:

- Visual Inspection: Plotting the time series is the first and often most effective step. Look for clear repeating cycles, e.g., yearly peaks in ice cream sales or monthly fluctuations in electricity usage.

- Autocorrelation Function (ACF) and Partial Autocorrelation Function (PACF): These plots reveal correlations between data points separated by various lags. Significant spikes at lags corresponding to the seasonal period (e.g., 12 for monthly data) indicate seasonality.

- Seasonal Decomposition: Methods like classical decomposition or STL decomposition break down the time series into its trend, seasonal, and residual components, explicitly revealing seasonal patterns.

- Spectral Analysis: This technique uses Fourier transforms to identify dominant frequencies in the data. Frequencies corresponding to seasonal periods indicate seasonality.

Example: If you observe peaks in sales data every December, this suggests a yearly seasonality.

Q 5. Explain the concept of autocorrelation and its significance in time series analysis.

Autocorrelation measures the correlation between a time series and its lagged version. In simpler terms, it tells us how much a value at one time point is related to its past values. High autocorrelation suggests dependence between consecutive or nearby observations. For example, yesterday’s stock price might influence today’s price.

Significance in Time Series Analysis:

- Identifying Stationarity: A stationary time series will have autocorrelation that decays quickly as the lag increases.

- Model Building: Autocorrelation helps determine the order of AR and MA components in ARIMA models. The ACF and PACF plots guide this process.

- Model Diagnostics: The autocorrelation of the residuals after model fitting indicates whether the model captures the underlying dependencies in the data adequately. High residual autocorrelation implies a poorly fitting model.

Understanding autocorrelation is critical for building appropriate time series models and assessing their accuracy.

Q 6. Compare and contrast AR, MA, and ARIMA models.

AR, MA, and ARIMA are all types of time series models that capture different aspects of temporal dependence:

- AR (Autoregressive): Models the current value as a linear combination of its past values. An AR(p) model uses the previous ‘p’ values. Think of it as predicting today’s temperature based on the temperatures of the previous ‘p’ days.

- MA (Moving Average): Models the current value as a linear combination of past forecast errors (residuals). An MA(q) model uses the previous ‘q’ errors. Imagine adjusting your temperature prediction based on how much your previous predictions were off.

- ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average): Combines AR and MA components and includes differencing (the ‘I’ part) to handle non-stationarity. An ARIMA(p,d,q) model uses ‘p’ autoregressive terms, ‘d’ levels of differencing, and ‘q’ moving average terms. It’s a flexible model that can capture many complex time series patterns.

Comparison: AR models focus on past values, MA models on past errors, and ARIMA combines both while handling non-stationarity. The choice depends on the characteristics of the time series.

Q 7. How do you evaluate the accuracy of a time series forecasting model?

Evaluating the accuracy of a time series forecasting model requires assessing how well its predictions match the actual values. Several metrics are commonly used:

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): The average absolute difference between the predicted and actual values. Easy to interpret, but doesn’t penalize large errors disproportionately.

- Mean Squared Error (MSE): The average squared difference between the predicted and actual values. Penalizes larger errors more heavily than MAE.

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): The square root of MSE. Has the same units as the time series, making it easier to interpret than MSE.

- Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): The average absolute percentage difference between predicted and actual values. Useful for comparing models across different datasets with varying scales. Can be undefined if an actual value is zero.

- Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (sMAPE): An alternative to MAPE that avoids the problem of undefined values when an actual value is zero.

In addition to these metrics, visual inspection of forecast plots helps assess model fit and identify potential issues. Backtesting—evaluating the model’s performance on historical data—is crucial to assess its robustness and generalization ability. Finally, consider the practical implications of forecast errors. A small RMSE might be acceptable in some cases but unacceptable in others (e.g., forecasting energy consumption vs. predicting stock prices).

Q 8. What are some common metrics used to evaluate time series forecasting models?

Evaluating the performance of a time series forecasting model requires a range of metrics, each offering a different perspective on accuracy and reliability. We don’t just look at one number; a holistic approach is crucial.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): This measures the average absolute difference between predicted and actual values. It’s easy to understand and interpret, representing the average magnitude of errors. A lower MAE indicates better accuracy.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): Similar to MAE, but it squares the errors before averaging and then takes the square root. This gives more weight to larger errors, penalizing significant deviations more heavily. It’s particularly useful when large errors are more costly.

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): This expresses errors as a percentage of the actual values. This is beneficial for comparing models across datasets with different scales. However, it’s undefined when actual values are zero.

Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE): An improvement over MAPE, SMAPE addresses the issue of undefined values when actual values are zero by including the predicted value in the denominator. It provides a more robust percentage error metric.

R-squared (R²): This measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (actual values) that’s predictable from the independent variables (model’s predictions). A higher R² indicates a better fit, but it’s important to remember that a high R² doesn’t automatically mean a good model, especially with complex time series.

Imagine predicting daily stock prices. A small MAE might be acceptable for a long-term investment strategy but unacceptable for high-frequency trading. The choice of metric depends heavily on the context and the cost associated with different types of errors.

Q 9. Describe the process of building an ARIMA model.

Building an ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) model involves a systematic process, often iterative and requiring careful consideration of the data’s characteristics. It’s like assembling a complex machine; each part plays a crucial role.

Data Preprocessing: This is the foundational step. It involves checking for missing values, outliers (which we’ll address later), and ensuring the data is stationary (constant mean and variance over time).

Differencing: If the data isn’t stationary, differencing is applied to make it so. This involves subtracting consecutive data points to remove trends. We might need to difference multiple times (e.g., second-order differencing) to achieve stationarity.

Order Identification (p, d, q): This is arguably the most critical step. We determine the orders (p, d, q) of the ARIMA model:

p (Autoregressive order): The number of lagged values of the dependent variable used as predictors. It represents the dependence on past values.

d (Differencing order): The number of times the data was differenced to achieve stationarity.

q (Moving Average order): The number of lagged forecast errors used as predictors. It accounts for the influence of past forecast errors.

Techniques like ACF (Autocorrelation Function) and PACF (Partial Autocorrelation Function) plots help identify suitable values for p and q.

Model Estimation: Once the order (p, d, q) is determined, the model parameters are estimated using statistical methods, often maximum likelihood estimation.

Model Diagnostics: We assess the model’s fit by examining residual plots (checking for randomness and constant variance), performing hypothesis tests (like the Ljung-Box test for autocorrelation in residuals), and evaluating the chosen metrics (MAE, RMSE, etc.). If the diagnostics are unsatisfactory, we may need to adjust the order or try other transformations.

Forecasting: Finally, the estimated model is used to generate forecasts for future time periods.

Imagine forecasting electricity demand. We’d preprocess the data, likely difference it to remove seasonal trends (daily or yearly), identify the ARIMA order based on ACF/PACF plots, estimate the model parameters, diagnose the model’s performance, and then predict future electricity demand.

Q 10. What are the limitations of ARIMA models?

While ARIMA models are powerful tools, they have limitations that need to be acknowledged:

Assumption of Stationarity: ARIMA models assume the data is stationary. Non-stationary data requires differencing, which can sometimes complicate the model and lead to less accurate forecasts.

Linearity Assumption: ARIMA models assume a linear relationship between the time series and its past values. Nonlinear relationships might not be captured accurately.

Difficulty in Handling Seasonality: While SARIMA (Seasonal ARIMA) addresses seasonality, it can become complex to tune and interpret, especially with multiple seasonal components.

Sensitivity to Outliers: Outliers can significantly influence model estimation and forecast accuracy.

Limited Ability to Handle External Regressors: Standard ARIMA models don’t directly incorporate external factors that might influence the time series (e.g., economic indicators influencing sales data).

For instance, forecasting stock prices with ARIMA might be problematic because of the inherent nonlinearity in the market and the impact of external news and events. More advanced techniques are often needed for greater accuracy and robustness in these scenarios.

Q 11. Explain the concept of differencing in time series analysis.

Differencing in time series analysis is a crucial technique used to transform non-stationary data into stationary data. Stationarity, meaning constant statistical properties over time (like constant mean and variance), is a fundamental assumption for many time series models, including ARIMA. Think of it as stabilizing the data.

The process involves subtracting consecutive data points. First-order differencing is simply:

yt - yt-1where yt is the value at time t. Higher-order differencing (e.g., second-order) involves differencing the differenced series. The order of differencing (d in ARIMA) indicates how many times this operation is performed.

Imagine a time series showing yearly sales that consistently increase each year. This is non-stationary because the mean is not constant. First-order differencing would subtract last year’s sales from this year’s, resulting in a series of year-over-year changes. This differenced series might be closer to stationarity.

Q 12. How do you handle outliers in time series data?

Outliers in time series data are extreme values that deviate significantly from the overall pattern. They can severely impact the accuracy of forecasting models. Handling outliers requires careful consideration.

Identification: Visual inspection of the time series plot is a good starting point. Boxplots or other statistical methods can help identify potential outliers.

Winzorization or Clipping: These methods replace outliers with less extreme values. Winzorization replaces outliers with the highest or lowest non-outlier value, while clipping replaces outliers with a predetermined threshold.

Robust Methods: Employing robust statistical methods like robust regression or using models less sensitive to outliers (e.g., certain types of robust ARIMA models) can minimize the outlier’s influence.

Removal (with caution): Removing outliers should be a last resort and only done if there’s a clear reason to believe they’re errors or anomalies unrelated to the underlying process. Always document and justify any data removal.

Consider a sensor measuring temperature. A sudden spike could be a faulty sensor reading (an outlier). Winzorization might replace this spike with a more plausible value, while removing it would risk losing valuable information if the spike was a genuine, albeit unusual, event.

Q 13. What is the purpose of Box-Cox transformation in time series analysis?

The Box-Cox transformation is a powerful technique used to stabilize the variance of a time series and make it more normally distributed. Many time series models (including ARIMA) perform better with data that’s closer to a normal distribution and has constant variance (homoscedasticity).

The transformation is defined as:

yλ = (yλ - 1) / λ if λ ≠ 0ln(y) if λ = 0where y is the original data and λ is the transformation parameter. The optimal value of λ is often determined using maximum likelihood estimation, aiming to make the transformed data as close to normally distributed as possible.

Imagine a time series with increasing variance over time. The Box-Cox transformation might reduce this variance, making the data more suitable for an ARIMA model. This can significantly improve forecast accuracy.

Q 14. What are some advanced time series models beyond ARIMA?

ARIMA models are valuable, but many more sophisticated techniques are available for time series analysis, each better suited to specific data characteristics and modeling challenges.

Exponential Smoothing Methods (Holt-Winters, etc.): These are powerful and flexible methods, particularly useful for capturing trends and seasonality in a relatively simple way. They are less reliant on the assumption of stationarity.

Vector Autoregression (VAR): This model analyzes the relationships between multiple time series simultaneously. It’s useful for situations where several interacting time series influence each other (e.g., forecasting sales of related products).

State Space Models (Kalman Filter): These are powerful models that represent the time series using a hidden state that evolves over time. They are excellent for handling noisy data and incorporating external information.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks (Recurrent Neural Networks): These are deep learning models capable of capturing complex nonlinear patterns in time series data. They are powerful but require significantly more data and computational resources than traditional methods.

Prophet (from Meta): Specifically designed for business time series data with strong seasonality and trend components, Prophet combines statistical modeling with machine learning elements for robustness.

For example, predicting electricity consumption on a smart grid might benefit from state space models to account for noisy sensor readings and external factors like weather patterns. Forecasting customer churn, however, might be better suited to LSTM networks to capture complex customer behavior.

Q 15. (e.g., Prophet, LSTM, GARCH) Explain one in detail.

Let’s delve into Prophet, a time series forecasting model developed by Facebook. It’s particularly well-suited for business time series data that exhibits strong seasonality and trend. Unlike many traditional statistical models, Prophet is robust to missing data and outliers, making it a practical choice for real-world applications where data isn’t always perfect.

At its core, Prophet uses an additive model where the time series is decomposed into several components: trend, seasonality, and holidays.

- Trend: This component captures the overall long-term direction of the time series, often modeled using a piecewise linear function. This allows the trend to change its slope at various points, accommodating changes in growth rate.

- Seasonality: Prophet handles both yearly and weekly seasonality by default using Fourier series. This allows it to capture periodic patterns within the data. You can easily customize it to include other periodicities.

- Holidays: You can specify important holidays or events that might impact the time series. Prophet allows you to incorporate these as regressors, adding extra flexibility.

The model is fitted using Bayesian techniques, providing uncertainty intervals around the forecasts, which is crucial for understanding the reliability of predictions. This is significantly more informative than just point estimates.

Example: Imagine forecasting daily website traffic. Prophet can effectively capture the weekly seasonality (lower traffic on weekends), yearly seasonality (higher traffic during holiday seasons), and perhaps even the impact of specific marketing campaigns (holidays).

# Example using Python's Prophet library from prophet import Prophet # ... data loading and preprocessing ... m = Prophet() m.fit(df) future = m.make_future_dataframe(periods=365) forecast = m.predict(future)Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. How do you choose the appropriate model for a given time series dataset?

Choosing the right time series model is a crucial step. It depends heavily on the characteristics of your data and your forecasting goals. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, but a systematic approach is key.

- Data Exploration: Begin by thoroughly examining your time series data. Visualize it using plots to identify patterns such as trend, seasonality, cyclical behavior, and outliers. Calculate key statistics like autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation to understand the dependencies within the data.

- Stationarity: Check if your data is stationary (meaning its statistical properties like mean and variance are constant over time). Many models assume stationarity; if not, you’ll need to apply transformations (like differencing or logging) to stabilize it.

- Model Selection: Consider the following factors:

- Data characteristics: Is the data linear or non-linear? Does it exhibit strong seasonality or trend? Is it noisy or relatively smooth?

- Forecasting horizon: Short-term forecasts might benefit from simpler models like ARIMA, while long-term forecasts might require more complex models like Prophet or LSTM.

- Interpretability vs. Accuracy: Some models (like ARIMA) offer more interpretability, while others (like neural networks) might achieve higher accuracy but be harder to understand.

- Model Evaluation: Use appropriate metrics (like RMSE, MAE, MAPE) to compare the performance of different models on a hold-out dataset. Don’t rely on just one metric; consider multiple to get a comprehensive assessment.

Example: For a stable time series with clear seasonality and trend, Prophet might be suitable. For a highly volatile, non-linear series, an LSTM could be a better choice. For a shorter-term forecast with a relatively simple structure, ARIMA may suffice.

Q 17. Describe your experience with time series databases (e.g., InfluxDB, TimescaleDB).

My experience with time-series databases centers around TimescaleDB, which I’ve used extensively in projects requiring high-volume, high-velocity data ingestion and analysis. TimescaleDB extends PostgreSQL, offering features specifically optimized for time-series data. This combination provides a robust and scalable solution.

Specifically, I’ve utilized its features for:

- High-speed data ingestion: TimescaleDB’s parallel ingestion capabilities are crucial for handling the large influx of data points common in time-series applications.

- Data compression: The built-in compression algorithms significantly reduce storage costs while maintaining query performance.

- Advanced querying: The ability to perform efficient time-based aggregations and filtering is essential for extracting meaningful insights from large datasets. TimescaleDB’s specialized functions make these operations very fast.

- Hypertables: This feature allows efficient partitioning and chunking of data, facilitating improved performance and scalability.

In one project involving real-time sensor data, TimescaleDB’s performance was critical. We processed millions of data points per day, and the database handled this volume without significant performance degradation. The ability to seamlessly integrate with other data processing tools (like Grafana for visualization) further enhanced its value.

Q 18. Explain the concept of Granger causality.

Granger causality is a statistical concept used to determine whether one time series is helpful in forecasting another. It doesn’t imply actual causality in a physical sense, but rather a predictive relationship. If Time series X ‘Granger-causes’ Time series Y, it means that past values of X improve the prediction of Y, above and beyond what can be achieved using past values of Y alone.

The test involves comparing the performance of two models:

- Model 1: Predicts Y using only past values of Y.

- Model 2: Predicts Y using past values of both X and Y.

If Model 2 significantly outperforms Model 1 (meaning the addition of X improves the forecast), then we say X Granger-causes Y. This is typically assessed using statistical tests, comparing the residual variances or likelihoods of the two models. The null hypothesis is that X does *not* Granger-cause Y.

Important Note: Correlation does not equal causation. Granger causality is just a statistical test; it doesn’t prove a direct causal link. Other factors could be influencing both X and Y.

Example: Imagine analyzing stock prices of two companies. If past movements in Company A’s stock price help predict future movements in Company B’s stock price better than using only Company B’s past data, then Company A’s stock price Granger-causes Company B’s stock price (statistically speaking).

Q 19. What are the challenges of working with high-frequency time series data?

Working with high-frequency time series data presents unique challenges:

- Data Volume and Velocity: The sheer volume of data generated can overwhelm traditional storage and processing systems. Real-time processing is often required.

- Noise and Irregularities: High-frequency data is often very noisy, containing many spurious fluctuations. Identifying true patterns can be difficult. Irregularities, such as missing data points or measurement errors, are also more common.

- Computational Complexity: Analyzing and modeling high-frequency data can be computationally intensive, demanding powerful hardware and efficient algorithms.

- Storage Costs: The massive volume of data requires substantial storage capacity, leading to high costs.

- Data Synchronization and Consistency: Maintaining data synchronization across multiple sources and ensuring data consistency becomes particularly important.

Example: Imagine analyzing tick-level data from a stock exchange. The volume is immense, and even minor errors can significantly affect analysis. Efficient data ingestion, cleaning, and specialized algorithms are necessary to handle such data effectively.

Q 20. How do you handle trend and seasonality in time series forecasting?

Handling trend and seasonality is crucial for accurate time series forecasting. There are several techniques:

- Decomposition Methods: These techniques separate the time series into its components (trend, seasonality, residuals). Classical decomposition methods (e.g., moving averages) can be used, or more sophisticated methods like STL (Seasonal and Trend decomposition using Loess) can be employed. After decomposition, you can model each component separately and recombine them for forecasting.

- Differencing: For removing trends, differencing (subtracting consecutive data points) is a common technique. This transforms a non-stationary series into a stationary one, suitable for many models. First-order differencing removes a linear trend; higher-order differencing can handle more complex trends.

- Seasonal Differencing: Similar to regular differencing, but subtracts data points from a previous season (e.g., subtracting the value from last year’s same month).

- Modeling Seasonality Directly: Many models (like Prophet or ARIMA models with seasonal components) can explicitly model seasonality using trigonometric functions or other periodic terms.

- Regression with Seasonal Dummies: You can include indicator (dummy) variables to represent different seasons as regressors in a regression model.

The choice of method depends on the specific characteristics of your data. For example, if the seasonality is relatively stable, modeling it directly within the model might be sufficient. If the trend is highly non-linear, differencing might not be the most effective approach, and a more flexible method like Prophet might be preferred.

Q 21. Explain your experience with feature engineering for time series data.

Feature engineering for time series data involves creating new features from existing ones to improve model performance. It’s a crucial aspect of building accurate and robust forecasting models. Effective feature engineering leverages the temporal nature of the data.

Examples of common features:

- Lagged Variables: Past values of the time series itself (e.g., using previous day’s sales to predict today’s sales). The optimal lag depends on the autocorrelation of the data.

- Rolling Statistics: Calculate moving averages, standard deviations, or other statistics over a rolling window. This helps smooth out noise and capture trends.

- Time-Based Features: Include features like day of the week, month, quarter, or holiday indicators. These capture seasonality and other time-related effects.

- External Regressors: Incorporate data from other sources, such as weather data, economic indicators, or marketing campaigns, that may influence the target time series.

- Time since last event: In event-based time series, this is particularly valuable.

- Feature Interactions: Create new features by combining existing ones, such as interaction terms between lagged variables and seasonality indicators.

Example: In a retail sales forecasting project, I created features like lagged sales (previous week, previous month), rolling averages (7-day, 30-day), day of the week, month, holiday indicators, and even incorporated external data on local weather patterns. This resulted in a significant improvement in forecast accuracy compared to using just the raw sales data.

Q 22. Describe the concept of cross-validation in time series analysis.

Cross-validation in time series analysis is crucial because we can’t simply split our data randomly like in other machine learning tasks. The inherent temporal dependence violates the independence assumption needed for standard techniques like k-fold cross-validation. Instead, we need methods that respect the order of observations.

Common approaches include:

- Forward Chaining (Rolling Forecasting Origin): We train our model on an initial segment of the data and forecast a short period ahead. Then, we expand the training set by including the next few observations and forecast another short period, iteratively rolling forward. This mimics real-world forecasting where we constantly update our models with new data. Think of it like building a tower, brick by brick, always using the previously built section as the base.

- Time Series Splitting: This creates multiple train-test splits, each respecting the temporal order. For example, we could create splits where the first 70% is the training set and the last 30% is the test set; the first 80% the training set, and the remaining 20% the test set; and so on. This allows us to measure model performance across various segments and assess robustness.

- Block Cross-Validation: This splits the data into consecutive blocks of data (e.g., years, months). One block is used for testing, and the remaining blocks are used for training. This strategy addresses the temporal dependencies between data points effectively. It’s particularly useful for long time series with various patterns.

Choosing the right method depends on the specific time series and the forecasting horizon. Forward chaining is preferred for scenarios requiring more realistic forecasting scenarios where predictions are updated gradually with new data. Time Series Splitting and Block Cross-Validation offer a more comprehensive evaluation across various time segments.

Q 23. What is your experience with time series decomposition?

Time series decomposition is a powerful technique to separate a time series into its constituent components: trend, seasonality, and residual (noise). Understanding these components provides valuable insights into the underlying patterns and helps build more accurate forecasting models.

My experience encompasses both classical decomposition methods (additive and multiplicative) and more advanced techniques like STL (Seasonal and Trend decomposition using Loess). Classical methods assume a particular relationship between the components (additive: Y = Trend + Seasonality + Residual; multiplicative: Y = Trend * Seasonality * Residual). STL offers a more flexible approach, adapting to different patterns in the data.

I’ve applied decomposition in various scenarios, including:

- Identifying seasonality patterns: For example, decomposing monthly retail sales to isolate seasonal fluctuations due to holidays or weather changes.

- Trend analysis: Examining the long-term growth or decline in a time series, like the overall upward trend in global temperatures.

- Residual analysis: Detecting outliers or unusual patterns in the data that may require further investigation.

The choice of method often depends on the characteristics of the time series. If the amplitude of seasonal fluctuations appears roughly constant over time, an additive model is usually appropriate. However, if the seasonal fluctuations are proportional to the level of the time series, a multiplicative model is more suitable.

Q 24. How would you approach forecasting a time series with multiple seasonalities?

Forecasting time series with multiple seasonalities (e.g., daily, weekly, yearly) presents a significant challenge. Standard seasonal models like ARIMA only account for a single seasonality. To overcome this, we can employ a few strategies:

- Multiple Seasonal ARIMA (MSARIMA): This extension of ARIMA incorporates additional seasonal components for each periodicity. It’s a powerful model but can be complex to specify and requires careful selection of orders (p, d, q) for each seasonal component.

- Regression with Seasonal Dummies: Introduce indicator variables (dummy variables) for each seasonal component. For example, daily, weekly, and monthly dummy variables. A regression model (linear or otherwise) can then capture the relationships between the time series and these seasonal indicators. This approach can handle various seasonalities but may not capture complex interactions or autocorrelations.

- Prophet (from Facebook): A robust open-source model designed for business time series. It can automatically detect and model multiple seasonalities (yearly, weekly, daily) and handles missing data and trend changes well. Prophet is often a simpler, more effective solution, though it requires careful hyperparameter tuning.

- TBATS (Trigonometric, Box-Cox, ARIMA, and Exponential Smoothing State Space Model): This model combines features of several time series models. It’s particularly adept at handling multiple seasonalities along with trend patterns and outliers. It’s powerful but can be computationally intensive.

The selection of an appropriate model depends on data characteristics, computational resources, and interpretability requirements. I typically start with simpler models like regression with seasonal dummies or Prophet, moving towards more complex models (MSARIMA or TBATS) only if needed to achieve sufficient forecasting accuracy.

Q 25. Explain your understanding of vector autoregression (VAR) models.

Vector Autoregression (VAR) models are a powerful tool for analyzing the interdependencies between multiple time series. Unlike univariate models that focus on a single series, VAR models analyze the relationship between several variables simultaneously. Imagine a system where several variables influence each other over time – stock prices, interest rates, and inflation might be examples.

A VAR model assumes that each variable can be expressed as a linear function of its own past values and the past values of other variables in the system. The order of the model (p) specifies how many past lags are included. A VAR(p) model can be represented as:

Xt = A1Xt-1 + A2Xt-2 + ... + ApXt-p + εtwhere:

Xtis a vector of time series at time t.Aiare coefficient matrices.εtis a vector of error terms.

VAR models allow us to analyze:

- Impulse Response Functions (IRFs): How a shock to one variable affects other variables over time.

- Forecast Error Variance Decomposition (FEVD): The proportion of the forecast error variance of each variable explained by shocks to other variables.

- Granger Causality Tests: Determining whether one variable helps predict another variable.

The main challenges with VAR models include determining the optimal lag order (p) and ensuring that the data is stationary (meaning that the statistical properties of the time series, such as mean and variance, do not change over time). I have extensive experience in employing techniques like information criteria (AIC, BIC) for lag order selection and differencing for achieving stationarity.

Q 26. Describe your experience using any statistical software for time series analysis (e.g., R, Python).

I have extensive experience using both R and Python for time series analysis. In R, I’m proficient with packages like forecast (for ARIMA, ETS, and other forecasting methods), tseries (for time series analysis functions), and vars (for VAR models). I also utilize ggplot2 for creating effective visualizations of time series data and model outputs.

In Python, I primarily utilize libraries such as statsmodels (for ARIMA, VAR, and other statistical modeling), pmdarima (for automated ARIMA model selection), and Prophet (for robust business time series forecasting). pandas provides excellent data manipulation capabilities, while matplotlib and seaborn are used for visualization.

I am comfortable with both environments and choose the best tool based on the specific project requirements and team preferences. For example, R’s forecast package offers a user-friendly interface for many forecasting tasks, whereas Python’s flexibility and extensive ecosystem of libraries are better suited for more complex projects or integrating time series analysis with other machine learning techniques.

Q 27. What is your experience with real-world applications of temporal analysis?

My experience with real-world applications of temporal analysis is extensive, covering diverse domains. Here are some examples:

- Finance: Stock price forecasting, risk management, portfolio optimization, and algorithmic trading. I have worked on predicting asset returns using ARIMA, GARCH, and VAR models, taking into account market volatility and macroeconomic indicators.

- Retail: Sales forecasting, inventory management, demand planning. This involves analyzing historical sales data to predict future demand, optimizing inventory levels, and planning promotional activities. I have utilized exponential smoothing, ARIMA, and machine learning techniques to achieve high accuracy in these tasks.

- Energy: Load forecasting for electricity grids, renewable energy production prediction. Working with time series data on energy consumption patterns, weather forecasts, and renewable generation capacity to optimize energy grid operations and improve the reliability of power supply. I have also implemented robust forecasting models capable of handling extreme weather events and seasonal changes.

- Healthcare: Disease outbreak prediction, patient monitoring, and hospital resource allocation. This involves modeling infectious disease dynamics and analyzing patient data (e.g., vital signs) to predict patient deterioration and optimize resource utilization.

Across these applications, the core principle remains consistent: understanding the temporal patterns in data is essential for making better predictions, optimizing resource allocation, and informing informed decision-making.

Q 28. Explain a challenging temporal analysis project you worked on and how you overcame the challenges.

One particularly challenging project involved forecasting electricity demand for a large utility company during a period of significant climate change impacts and infrastructure upgrades. The historical data exhibited both short-term seasonality (daily and weekly) and long-term trend changes due to shifts in consumer behaviour and technological advancements. Adding to the complexity, major infrastructure upgrades introduced sudden disruptions in the time series, violating many standard model assumptions.

The initial approach using traditional ARIMA models proved insufficient to capture the combined effects of seasonality, trends, and structural changes. The key challenge was to handle these discontinuous effects while still obtaining reliable and accurate forecasts.

To overcome these challenges, I employed a hybrid approach:

- Data Preprocessing: I used outlier detection and interpolation techniques to handle missing data and correct for some of the infrastructure-related disruptions, paying close attention to preserving the underlying temporal patterns.

- Model Selection: I experimented with several advanced models including TBATS and Prophet. Prophet’s ability to automatically handle trend changes proved particularly effective in mitigating the effects of infrastructure changes. Additionally, I incorporated external regressors into the model, including weather forecasts and planned maintenance schedules.

- Ensemble Modeling: I combined the forecasts from multiple models to enhance accuracy and robustness, and used cross-validation to assess their performance on unseen data.

The hybrid approach, incorporating data preprocessing, advanced modeling, and ensemble techniques, significantly improved the accuracy and reliability of our electricity demand forecasts. This successful outcome demonstrated the importance of adopting a flexible and adaptive strategy in dealing with complex real-world time series challenges.

Key Topics to Learn for Temporal Analysis Interview

- Time Series Decomposition: Understanding additive and multiplicative models, and applying them to decompose time series data into trend, seasonality, and residuals. Practical application: Forecasting sales based on historical data.

- ARIMA Modeling: Mastering the concepts of autoregressive (AR), integrated (I), and moving average (MA) processes, and their combinations. Practical application: Predicting stock prices or system failures.

- Forecasting Techniques: Familiarizing yourself with various forecasting methods beyond ARIMA, such as Exponential Smoothing (Holt-Winters), Prophet, and SARIMA. Practical application: Optimizing inventory management or resource allocation.

- Stationarity and its implications: Understanding how to check for and achieve stationarity in time series data, a crucial prerequisite for many analytical techniques. Practical application: Ensuring reliable results from ARIMA models.

- Model Evaluation Metrics: Knowing how to evaluate the accuracy of forecasting models using metrics like RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and AIC. Practical application: Selecting the best model for a given dataset.

- Time Series Anomaly Detection: Exploring techniques for identifying unusual patterns or outliers in time series data. Practical application: Fraud detection or system monitoring.

- Data Preprocessing for Temporal Data: Understanding techniques for handling missing values, outliers, and noise in time series data. Practical application: Preparing data for accurate model building.

- Causal Inference in Time Series: Exploring methods to establish causal relationships between time-dependent variables. Practical application: Analyzing the impact of marketing campaigns on sales.

Next Steps

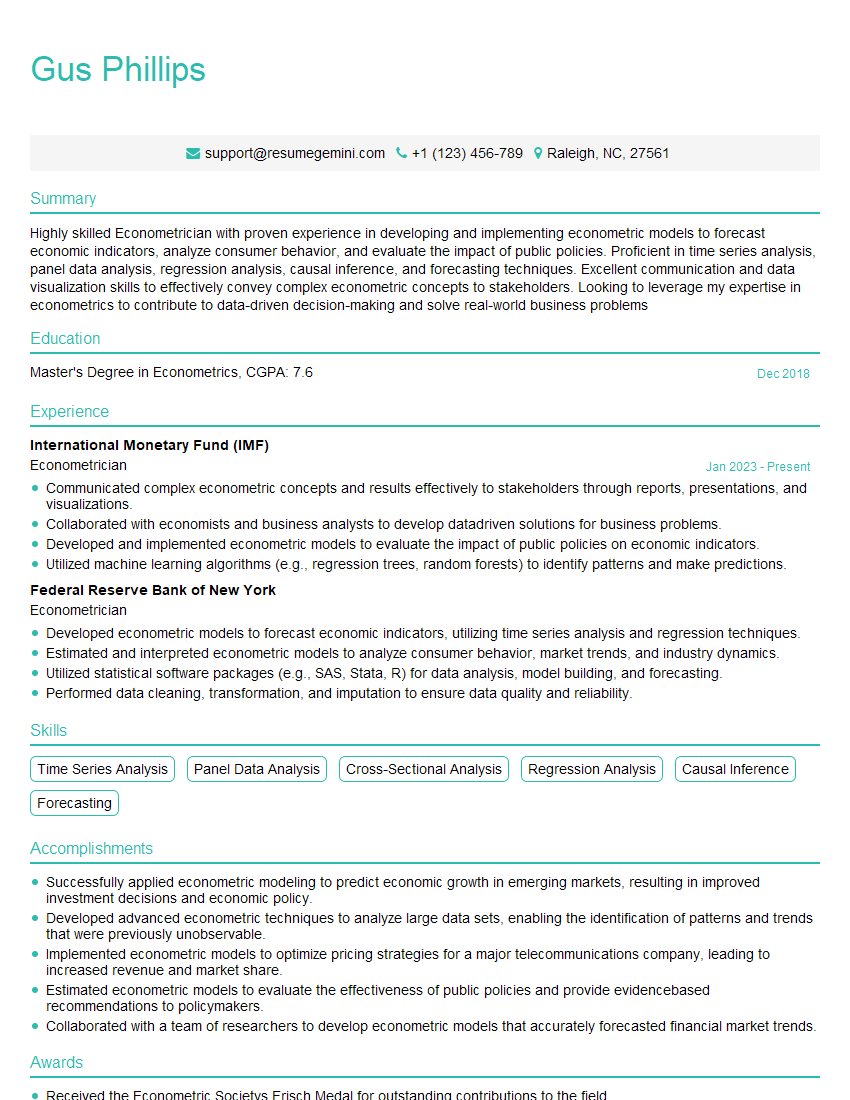

Mastering Temporal Analysis significantly enhances your career prospects in data science, forecasting, and related fields, opening doors to exciting roles with high demand. A strong resume is crucial for showcasing your skills to potential employers. Building an ATS-friendly resume is key to ensuring your application gets noticed. We recommend using ResumeGemini, a trusted resource, to craft a professional and impactful resume that highlights your expertise in Temporal Analysis. Examples of resumes tailored to Temporal Analysis are available to help you get started.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO