Preparation is the key to success in any interview. In this post, we’ll explore crucial Spatial and Statistical Analysis interview questions and equip you with strategies to craft impactful answers. Whether you’re a beginner or a pro, these tips will elevate your preparation.

Questions Asked in Spatial and Statistical Analysis Interview

Q 1. Explain the difference between spatial autocorrelation and spatial heterogeneity.

Spatial autocorrelation and spatial heterogeneity are both crucial concepts in spatial analysis, but they describe different aspects of spatial data. Spatial autocorrelation refers to the degree to which values at nearby locations are similar. Imagine a map of house prices: if expensive houses tend to cluster together, we have positive spatial autocorrelation. Conversely, if expensive and inexpensive houses are intermixed, we have low or negative spatial autocorrelation. Spatial heterogeneity, on the other hand, describes the variation in the relationship between variables across different locations. For example, the relationship between population density and air pollution might be strong in urban areas but weak in rural areas; this demonstrates spatial heterogeneity in the relationship.

Think of it this way: autocorrelation is about the *similarity* of values in space, while heterogeneity is about the *variation* in relationships across space. They are not mutually exclusive; you can have high autocorrelation within spatially heterogeneous regions.

Q 2. Describe various spatial interpolation methods and their suitability for different datasets.

Spatial interpolation estimates values at unsampled locations based on known values at sampled locations. Several methods exist, each with its strengths and weaknesses:

- Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW): This method assumes that the closer a point is to the unsampled location, the more similar its value is likely to be. It’s simple to understand and implement but can be sensitive to outliers and doesn’t account for spatial autocorrelation. It’s suitable for datasets where values are relatively smooth and the spatial dependency is weak.

- Kriging: A geostatistical method that models the spatial autocorrelation structure in the data. It’s more sophisticated than IDW, providing better estimates when spatial autocorrelation is significant. Different types of kriging exist (ordinary, universal, etc.), each suited to different scenarios and assumptions about the data. Kriging is effective when there is strong spatial correlation and your data shows a clear trend.

- Spline Interpolation: Creates a smooth surface that passes through or near the known data points. It’s good for creating visually appealing surfaces but might oversmooth areas with high variability. It can be applied across various types of datasets and is relatively straightforward to implement, but might not be suitable when specific spatial dependencies must be represented.

- Nearest Neighbor: The simplest method, it assigns the value of the nearest known point to the unsampled location. It’s computationally inexpensive but can result in a very rough, blocky surface, and unsuitable for continuous data. It’s useful for quick estimations or when data is extremely sparse.

The choice of method depends on the data characteristics (e.g., smoothness, autocorrelation), the presence of outliers, and the desired level of accuracy. For example, Kriging would be ideal for interpolating soil contamination levels, while IDW might suffice for interpolating elevation in a relatively flat area.

Q 3. What are the assumptions of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, and how are they violated in spatial data?

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression assumes several things that are frequently violated in spatial data:

- Independence of errors: OLS assumes that the residuals (errors) are independent. In spatial data, this is often violated due to spatial autocorrelation—nearby observations tend to be more similar, leading to spatially clustered residuals.

- Homoscedasticity: OLS assumes that the variance of the errors is constant across all observations. Spatial data might exhibit heteroscedasticity, where the variance of the errors varies across space, for example, if error variation is higher in densely populated areas.

- Linearity: OLS assumes a linear relationship between the independent and dependent variables. In spatial contexts, relationships might be non-linear, requiring transformations or non-linear regression techniques.

- No multicollinearity: OLS assumes that independent variables are not highly correlated. In spatial data, proximity itself can induce multicollinearity if spatial variables are involved (e.g., distance to a facility).

Violating these assumptions leads to biased and inefficient estimates. For instance, ignoring spatial autocorrelation can lead to inflated R-squared values and incorrect inferences about the significance of predictors.

Q 4. How do you handle spatial autocorrelation in regression analysis?

Spatial autocorrelation in regression analysis needs to be addressed to obtain reliable results. Several strategies exist:

- Spatial regression models: These models explicitly account for spatial autocorrelation, such as spatial lag models (SAR) and spatial error models (SEM). SAR models include a spatially lagged dependent variable, while SEM models incorporate a spatially autocorrelated error term. These models use spatial weights matrices to define the spatial relationships between observations.

- Generalized Least Squares (GLS): This method corrects for heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation by transforming the data using a suitable weighting matrix that accounts for the observed spatial patterns. It can be applied before performing OLS.

- Robust Standard Errors: If the autocorrelation is not too severe, using robust standard errors (such as those from a sandwich estimator) can provide more reliable inferences about the model coefficients.

- Spatial filtering: This technique involves transforming the data to remove or reduce the spatial autocorrelation before applying OLS. However, this approach can lose some valuable spatial information.

The best approach depends on the nature and strength of the spatial autocorrelation and the characteristics of the data. Diagnostic tests such as Moran’s I (discussed below) are crucial for identifying and characterizing the autocorrelation.

Q 5. Explain the concept of Moran’s I and its interpretation.

Moran’s I is a spatial autocorrelation statistic that measures the overall spatial autocorrelation in a dataset. It ranges from -1 to +1:

- Positive values (close to +1) indicate positive spatial autocorrelation; similar values tend to cluster together.

- Negative values (close to -1) indicate negative spatial autocorrelation; dissimilar values tend to cluster together.

- Values near 0 indicate a lack of spatial autocorrelation.

Moran’s I is calculated using a spatial weights matrix, which defines the spatial relationships between observations (e.g., contiguity or distance-based weights). A significant Moran’s I (after testing for significance) suggests the presence of spatial autocorrelation, which needs to be considered in the subsequent spatial analysis.

For example, a high positive Moran’s I for a map of unemployment rates suggests that high unemployment tends to cluster geographically. This could be explained by factors like shared industry sectors or lack of transportation options.

Q 6. What are geostatistical techniques, and when are they appropriate?

Geostatistical techniques are a set of methods used to analyze spatially referenced data, particularly when the data exhibit spatial autocorrelation and uncertainty. They focus on characterizing the spatial dependence structure and making predictions (interpolation) at unsampled locations. Some common techniques include:

- Kriging: As mentioned earlier, a powerful interpolation method that accounts for spatial autocorrelation.

- Variogram analysis: This technique examines the spatial variation of data by measuring the semi-variance at different lags (distances). The variogram helps to model the spatial autocorrelation structure, which is crucial for kriging.

- Co-kriging: Extends kriging to multiple variables, incorporating the spatial correlation between them.

Geostatistical techniques are appropriate when:

- Data are spatially referenced and exhibit spatial autocorrelation.

- There’s a need for spatial prediction (interpolation) at unsampled locations.

- Uncertainty in the predictions needs to be quantified.

Examples include applications in environmental monitoring (e.g., soil contamination, air quality), resource management (e.g., ore grade estimation), and epidemiology (e.g., disease mapping).

Q 7. Discuss the differences between kriging and inverse distance weighting.

Both Kriging and Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) are spatial interpolation methods, but they differ significantly in how they handle spatial autocorrelation:

- IDW is a deterministic method that assigns weights to neighboring points based solely on their distance to the unsampled location. It doesn’t explicitly model the spatial autocorrelation structure in the data. This simplicity makes it computationally efficient, but it can lead to inaccurate predictions if the spatial pattern is complex.

- Kriging is a geostatistical method that explicitly models the spatial autocorrelation structure using a variogram or covariance function. It uses this model to determine optimal weights for the neighboring points, leading to more accurate predictions, particularly when spatial autocorrelation is strong. Kriging also provides an estimate of the prediction uncertainty, a crucial aspect often lacking in simpler methods.

In essence, IDW is a simpler, faster method suitable for situations where spatial autocorrelation is weak or unknown, while Kriging is a more sophisticated method that explicitly accounts for spatial autocorrelation and provides uncertainty estimates, making it more suitable for situations with strong spatial dependence and when accurate and reliable estimates are needed. The choice depends on the data characteristics, computational resources, and the level of accuracy required.

Q 8. Describe different types of spatial data structures (e.g., raster, vector).

Spatial data structures organize geographic information for efficient storage, retrieval, and analysis. Two primary types are raster and vector data.

- Raster data represents spatial data as a grid of cells or pixels, each holding a value representing a characteristic (e.g., elevation, temperature). Think of a satellite image or a digital elevation model – each pixel has a specific value. This structure is excellent for representing continuous phenomena but can be less efficient for storing discrete features like roads.

- Vector data represents spatial data as points, lines, and polygons. Points represent locations, lines represent linear features (like roads), and polygons represent areas (like land parcels). Each feature has associated attributes. Vector data is superior for representing discrete features and is often used in geographic information systems (GIS) for managing map layers. For example, a road network or a boundary of a forest are better represented as vector data.

Choosing between raster and vector depends on the nature of the data and the intended analysis. Sometimes, data conversion between the two structures is necessary. For example, you might convert a raster elevation model to vector contours to analyze changes in elevation more easily.

Q 9. Explain the concept of spatial sampling and its importance.

Spatial sampling is the process of selecting a subset of locations from a spatial domain to collect data. Its importance lies in making data collection feasible and representative, particularly when dealing with large areas or expensive data acquisition. Think about trying to measure the average temperature of a whole country – it’s impossible to measure it at every point! So, we take samples at selected locations.

The method of sampling affects the results significantly. Random sampling, systematic sampling (e.g., grid-based), and stratified sampling (sampling within specific zones) are common techniques. The choice depends on the spatial distribution of the phenomenon and the research question. Poor sampling can lead to biased conclusions. For instance, only sampling in urban areas would provide a skewed view of air quality across an entire region.

Q 10. How do you handle missing data in spatial analysis?

Missing data is a significant challenge in spatial analysis, leading to bias and inaccurate results. Handling it requires careful consideration. Methods include:

- Deletion: Removing observations with missing data. This is simple but can lead to bias if missingness is not random.

- Imputation: Replacing missing values with estimated values. Methods include mean/median imputation (simple but can distort variability), hot-deck imputation (using similar observations), or more sophisticated methods like kriging (spatial interpolation using neighboring values).

- Model-based approaches: Incorporating missing data mechanisms into the statistical model, accounting for the uncertainty associated with missing data. This is usually a more advanced approach.

The best approach depends on the extent of missingness, its pattern, and the nature of the data. For example, in environmental monitoring, we might use kriging to interpolate missing pollution readings based on the values at nearby monitoring stations. Always document your chosen method and justify its use.

Q 11. What are some common challenges in working with large spatial datasets?

Large spatial datasets present several challenges:

- Storage and retrieval: Large datasets require significant storage space and efficient database management systems (DBMS) to access information quickly. Cloud computing solutions are often necessary.

- Processing power: Analyzing large datasets demands considerable computing power and often requires parallel processing techniques or high-performance computing (HPC) clusters.

- Visualization: Visualizing large datasets effectively can be challenging. Techniques like aggregation, subsetting, and interactive visualizations are crucial to managing complexity.

- Memory management: Working with large datasets requires careful memory management to avoid crashes or slow performance. Techniques like chunking data and using out-of-core algorithms are important.

For instance, analyzing global climate data requires handling massive datasets and employing specialized tools and techniques to extract meaningful insights. Efficient algorithms and optimized data structures are crucial for managing this complexity.

Q 12. Discuss different methods for visualizing spatial data.

Visualizing spatial data is crucial for understanding patterns and trends. Methods include:

- Maps: The most common method, showing data geographically. Types include choropleth maps (color-coded regions), dot density maps (dots representing occurrences), and isarithmic maps (contour lines showing continuous variation).

- 3D visualizations: Useful for visualizing terrain, building models, and representing changes over time. Software like ArcGIS Pro and QGIS offer extensive 3D capabilities.

- Interactive dashboards: Allow users to explore data through filtering, zooming, and other interactive controls. Tools like Tableau and Power BI are useful for creating dashboards from spatial data.

- Animations and time-series visualizations: Excellent for showing changes over time, such as population growth or spread of a disease.

The choice depends on the data and the message you want to convey. A choropleth map is great for showing variations in population density across regions, while an animation could show the migration patterns over a period of time.

Q 13. Explain the difference between point pattern analysis and spatial autocorrelation analysis.

Both point pattern analysis and spatial autocorrelation analysis deal with spatial relationships but address different questions.

- Point pattern analysis examines the spatial distribution of points. It aims to determine if the points are randomly distributed, clustered, or dispersed. Techniques include Ripley’s K-function and quadrat analysis. For example, analyzing the locations of crime incidents helps to identify hotspots or areas with higher crime activity.

- Spatial autocorrelation analysis examines the degree to which values at nearby locations are similar. It measures the spatial dependence between observations. Techniques include Moran’s I and Geary’s C. For instance, analyzing spatial autocorrelation of house prices can reveal whether neighboring houses have similar prices (positive spatial autocorrelation) or dissimilar prices (negative spatial autocorrelation).

While seemingly distinct, these methods are often complementary. For example, you might first identify clusters of points using point pattern analysis and then examine the spatial autocorrelation of a variable within those clusters.

Q 14. What is a spatial join, and how is it performed?

A spatial join combines attributes from two spatial layers based on their spatial relationships. Imagine you have a layer of parcels and a layer of schools. A spatial join can add information about the nearest school to each parcel.

It’s performed using a spatial relationship such as:

- Intersects: Attributes are joined if the geometries intersect (overlap).

- Contains: Attributes are joined if one geometry completely contains the other.

- Within: Attributes are joined if one geometry is completely within another.

- Nearest: Attributes are joined based on proximity, linking each feature to its nearest neighbor in the other layer.

Most GIS software provides tools to perform spatial joins. The specific method is often specified through a graphical user interface or code. The result is a new layer that combines the attributes of both original layers.

Q 15. Describe different types of spatial relationships (e.g., contiguity, distance).

Spatial relationships describe how geographic features interact or relate to each other. Understanding these relationships is crucial for spatial analysis. Two primary types are:

- Contiguity: This refers to the sharing of a common boundary. We can consider different types of contiguity: Queen contiguity (sharing a vertex or edge) and Rook contiguity (sharing an edge only). Imagine analyzing crime rates – Queen contiguity might show a relationship between crimes in adjacent blocks, even if only a corner touches, while Rook contiguity would only consider crimes in blocks sharing a full side.

- Distance: This defines the spatial separation between features. It can be Euclidean distance (straight-line distance), Manhattan distance (distance along a grid), or other more complex distance metrics that account for travel time or cost. For example, analyzing the spread of a disease, the Euclidean distance between infected individuals might help determine the extent of the outbreak. A more practical approach might be travel distance using road networks.

Beyond these two, other spatial relationships include direction (e.g., north of, south of), containment (one feature is entirely within another), and intersection (features overlap).

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Explain the concept of spatial regression models (e.g., spatial lag, spatial error).

Spatial regression models extend traditional regression analysis to account for the spatial dependence present in geographical data. Ignoring this dependence can lead to biased and inefficient estimates. Two common types are:

- Spatial Lag Model: This model includes a spatially lagged dependent variable as a predictor. The spatially lagged variable is the average value of the dependent variable in neighboring locations. This directly incorporates spatial autocorrelation into the model. For instance, if we’re modeling house prices, a spatial lag model would consider the average house price in nearby areas to predict the price of a specific house. The intuition is that nearby houses tend to have similar prices.

- Spatial Error Model: This model incorporates spatial dependence into the error term, assuming the errors are spatially autocorrelated. This means errors in nearby locations are correlated. The model accounts for this correlation using a spatial weight matrix. An example might be modeling crop yields; unobserved factors like soil quality or microclimate might influence yields in neighboring fields, leading to spatially autocorrelated errors.

The choice between these models depends on the nature of the spatial dependence. Diagnostic tests, like Moran’s I, can help determine the appropriate model.

Q 17. How do you assess the goodness of fit of a spatial model?

Assessing the goodness of fit for a spatial model involves several steps beyond traditional regression diagnostics. We need to evaluate both the global fit and the spatial aspects of the model. Key metrics include:

- R-squared: While still useful, R-squared alone is insufficient because it doesn’t account for spatial autocorrelation.

- AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion): These information criteria help compare different models, penalizing models with more parameters. Lower AIC and BIC values suggest a better fit.

- Likelihood Ratio Test: This test can compare nested models (e.g., spatial lag vs. no spatial effects).

- Spatial Autocorrelation Tests on Residuals: Moran’s I test on the model residuals is crucial. Significant spatial autocorrelation in residuals indicates that the model hasn’t adequately captured the spatial dependence. The residuals should ideally show no significant spatial pattern.

Visual inspection of residual maps is also important. Clustering or patterns in the residuals suggest potential model misspecification.

Q 18. What are some common software packages used for spatial analysis (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS, R)?

Several powerful software packages are widely used for spatial analysis. Each has its strengths:

- ArcGIS: A comprehensive Geographic Information System (GIS) software with extensive spatial analysis tools, strong visualization capabilities, and a large user community. It’s ideal for complex GIS tasks and tasks requiring advanced spatial data management.

- QGIS: A free and open-source GIS software with comparable functionality to ArcGIS. It’s a great cost-effective alternative, especially for those learning spatial analysis or working with limited budgets.

- R: A powerful programming language with numerous packages specifically designed for spatial analysis (e.g.,

spdep,sf,raster). It offers flexibility and allows for advanced statistical modeling and customization. R is excellent for custom analyses and advanced statistical modeling.

The best choice often depends on project requirements, budget, and the analyst’s familiarity with the software.

Q 19. Describe your experience with a specific spatial analysis project.

In a previous project, I analyzed the spatial distribution of air quality monitoring stations in a large metropolitan area. The goal was to assess the adequacy of the monitoring network and identify potential gaps in coverage. I used ArcGIS to manage the spatial data (station locations, pollution levels), performed spatial autocorrelation analysis to investigate clustering of monitoring stations, and created kernel density estimations to visualize pollution hotspots. I then used these results to propose an optimized network design, identifying areas where additional monitoring stations were needed to improve coverage and data quality. The project involved working with various data formats including shapefiles, point data, and raster data representing pollution levels.

Q 20. Explain how you would approach a spatial analysis problem involving disease mapping.

Analyzing a spatial disease mapping problem requires a multi-step approach:

- Data Collection and Preparation: Gather data on disease incidence (number of cases), population at risk, and potentially other covariates (e.g., socioeconomic factors, environmental variables). Ensure data are properly geo-referenced and in a suitable format (e.g., shapefiles, point data).

- Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis (ESDA): Use techniques like mapping disease rates, calculating spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I), and creating spatial clusters (e.g., using SaTScan) to identify potential hotspots and patterns in disease occurrence.

- Statistical Modeling: Consider using spatial regression models (e.g., Bayesian hierarchical models, spatial Poisson regression) to model disease risk factors and account for spatial dependence. Bayesian models allow us to incorporate prior knowledge and quantify uncertainty effectively.

- Model Evaluation and Interpretation: Assess model fit (using metrics described earlier) and interpret the results in a public health context, highlighting areas of high risk and identifying potential risk factors.

- Visualization and Communication: Present the findings using clear maps and visualizations to communicate the spatial patterns of disease and inform public health interventions.

It’s crucial to acknowledge and handle potential confounding factors and to communicate the uncertainties associated with the analysis. The choice of specific methods will depend on the type of disease, data availability, and the research question.

Q 21. Discuss your experience with different types of spatial data formats (e.g., shapefiles, GeoTIFFs).

I have extensive experience working with various spatial data formats. Here are some common ones:

- Shapefiles: A widely used geospatial vector format that stores geographic features as points, lines, or polygons. They are commonly used for representing boundaries, roads, and points of interest.

- GeoTIFFs: A georeferenced raster format storing gridded data, such as satellite imagery or elevation data. The georeferencing information is embedded within the file, facilitating easy integration with GIS software.

- GeoJSON: A text-based, open standard format commonly used for representing geographic features in a JSON structure, suitable for web mapping applications and data exchange.

- KML/KMZ: Keyhole Markup Language (KML) is an XML-based format used by Google Earth, often compressed as KMZ files. Useful for sharing 3D visualizations and geographic data.

The choice of format depends on the type of data, the intended use, and compatibility with the software being used. I’m proficient in converting between different formats as needed.

Q 22. How do you handle projection issues in spatial analysis?

Projection issues in spatial analysis arise because the Earth is a sphere, but we represent it on flat maps. This introduces distortions in distance, area, shape, and direction. Handling these issues is crucial for accurate analysis.

My approach involves understanding the projection of my data. First, I identify the coordinate reference system (CRS) of the spatial data. Different CRSs use different projections, and using incompatible ones leads to errors. I use tools like QGIS or ArcGIS to view the metadata and confirm the CRS. If the data uses an inappropriate projection for the analysis, I reproject it to a more suitable one. For instance, if I’m analyzing distances across a large area, I might choose an equidistant projection, preserving distances from a central point. For area calculations, an equal-area projection would be preferable. If working with multiple datasets, I ensure they all share the same CRS before any spatial operation. Failing to do this could result in inaccurate results, such as overlapping polygons that appear non-overlapping due to projection differences. Finally, I always document the projection used in my analysis to ensure reproducibility and transparency.

For instance, in a project analyzing deforestation in the Amazon, using a Mercator projection would severely distort area calculations near the poles, underestimating the actual extent of deforestation. Reprojecting the data to an equal-area projection, like Albers Equal-Area Conic, would be crucial for accurate analysis.

Q 23. Explain the concept of a buffer analysis.

A buffer analysis is a spatial operation that creates a zone around a geographic feature. Imagine drawing a circle around a point, or a band around a line or polygon; that’s essentially what a buffer does. The buffer zone represents a specified distance from the feature. This is incredibly useful for proximity analysis.

For example, let’s say you want to find all houses within a 1-kilometer radius of a school. You’d buffer the school location by 1 kilometer, creating a circular buffer. Then you’d overlay this buffer with a layer containing house locations. The houses that fall within the buffer are the ones within the desired distance of the school.

Buffer analysis can also be applied to more complex shapes and situations. For example, you could buffer a road network to determine areas accessible within a given driving time. Or, you could buffer multiple points to understand areas of high density. The buffer distance can be defined based on various criteria like time, cost, or any relevant measurement. The choice of buffer distance depends largely on the nature of the study, so justifying the selection is often crucial.

Q 24. Describe your experience with spatial data management and database systems.

My experience in spatial data management includes working extensively with various database systems, including PostgreSQL/PostGIS, MySQL with spatial extensions, and cloud-based solutions like AWS RDS for PostgreSQL. I’m proficient in designing and implementing spatial databases, ensuring data integrity and efficiency. I understand the importance of data schemas, indexing strategies (e.g., spatial indexes like R-trees), and data cleaning techniques to optimize query performance.

I’ve worked with different spatial data formats, including Shapefiles, GeoJSON, GeoPackages, and raster formats like GeoTIFF. Data migration between these formats is a familiar task for me, often requiring careful consideration of projection information and data quality. I have also built and maintain geospatial data pipelines using tools such as FME and Python libraries like GeoPandas and Rasterio. Furthermore, I’m comfortable employing version control (e.g., Git) for both data and code, adhering to best practices in data management to maintain reproducibility, collaboration, and data integrity.

Q 25. What are some ethical considerations in spatial data analysis?

Ethical considerations in spatial data analysis are paramount. The misuse of spatial data can have significant consequences. Several key areas require attention.

- Privacy: Spatial data often contains sensitive information about individuals or locations. Anonymization and aggregation techniques are crucial to protect individual privacy while preserving the utility of the data. Care must be taken to ensure compliance with relevant regulations like GDPR or HIPAA.

- Bias and Discrimination: Algorithms and analyses can perpetuate or amplify existing societal biases. For instance, using historical data that reflects discriminatory practices in housing or lending could lead to biased predictions. Careful consideration of potential biases and their mitigation is essential.

- Transparency and Accessibility: Spatial data analysis should be transparent and reproducible. Data sources, methods, and limitations should be clearly documented. Furthermore, data and results should be made accessible to relevant stakeholders, promoting accountability and avoiding the misuse of results.

- Representation and Context: The visualization and interpretation of spatial data should be done carefully, considering the broader context and avoiding misleading conclusions. For instance, using color schemes or projections that distort spatial relationships can manipulate the interpretation of results.

Ignoring these ethical considerations can lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes, erosion of public trust, and damage to reputation. Therefore, a robust ethical framework is essential throughout the entire spatial data analysis process.

Q 26. Explain your understanding of spatial econometrics.

Spatial econometrics extends traditional econometrics by explicitly accounting for spatial dependence and heterogeneity in data. Unlike standard regression models which assume independence between observations, spatial econometrics recognizes that observations near each other are often more similar than those farther apart. This spatial autocorrelation needs to be addressed for accurate and reliable results.

Spatial dependence can manifest in two main ways: spatial autocorrelation (similarity among neighboring values) and spatial heterogeneity (variation in relationships across space). Spatial econometric models incorporate spatial weights matrices to capture these relationships. These matrices define how observations are spatially related (e.g., contiguity, distance-based weights). Common spatial econometric models include Spatial Autoregressive (SAR), Spatial Error (SEM), and Spatial Durbin models. The choice of model depends on the nature of spatial dependence detected in the data.

For example, analyzing house prices would benefit from spatial econometrics. House prices in a particular neighborhood are likely to be influenced by the prices of neighboring houses. A standard regression model would overlook this spatial correlation, leading to biased and inefficient estimates. Spatial econometric models, on the other hand, can account for this spatial dependence, providing a more accurate analysis.

Q 27. How familiar are you with Bayesian spatial modeling?

Bayesian spatial modeling is a powerful framework for analyzing spatial data that incorporates prior knowledge and uncertainty explicitly into the analysis. Unlike frequentist approaches, Bayesian methods provide a full probability distribution for model parameters, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of uncertainty.

In Bayesian spatial modeling, we specify prior distributions for model parameters, reflecting our prior beliefs about their values. We then combine these priors with the likelihood function (which describes the probability of observing the data given the parameters) using Bayes’ theorem to obtain the posterior distribution. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are typically used to sample from the posterior distribution. This posterior distribution gives us estimates of model parameters and their uncertainties, allowing for robust inferences.

A key advantage of Bayesian methods is their ability to handle complex spatial patterns and incorporate various sources of information. For instance, incorporating expert knowledge into the prior distribution can improve model accuracy. Bayesian spatial modeling finds applications in various fields, including disease mapping, environmental monitoring, and ecological studies.

Tools like INLA and Stan are commonly used for Bayesian spatial modeling, offering efficient algorithms for fitting complex models.

Q 28. Describe your experience with machine learning techniques applied to spatial data.

I have significant experience applying machine learning techniques to spatial data. This involves leveraging the power of algorithms like Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and neural networks to solve spatial prediction, classification, and clustering problems.

For example, I’ve used Random Forests to predict land cover from remotely sensed imagery, taking advantage of the algorithm’s ability to handle high-dimensional data and non-linear relationships. SVMs have proven useful in classifying different types of urban land use based on spatial features and point-of-interest data. Neural networks, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), are effective for processing and analyzing raster data, for tasks such as image segmentation or object detection in satellite images.

However, the application of machine learning in a spatial context often requires careful consideration of spatial autocorrelation. Ignoring this can lead to overfitting or inaccurate predictions. Techniques like geographically weighted regression (GWR) can be incorporated into machine learning workflows to account for spatial heterogeneity. Furthermore, proper evaluation metrics, such as spatial accuracy metrics (e.g., kappa statistic) are necessary to assess the performance of the models in the spatial domain.

I am also familiar with deep learning architectures tailored to spatial data, like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) which are well-suited for modeling relationships in network data such as transportation systems or social networks.

Key Topics to Learn for Spatial and Statistical Analysis Interview

- Spatial Data Structures and Models: Understanding different spatial data formats (vector, raster), spatial relationships (adjacency, contiguity), and common spatial models (point patterns, spatial autocorrelation).

- Geostatistics: Mastering techniques like kriging for spatial interpolation and understanding variograms for analyzing spatial dependence. Practical application: Predicting soil properties across a region based on limited sample data.

- Spatial Regression: Familiarize yourself with spatial regression models (e.g., spatial lag, spatial error) and their application in analyzing spatially correlated data. Practical application: Modeling the effect of proximity to a pollution source on property values.

- Spatial Econometrics: Explore the intersection of spatial analysis and econometrics, understanding concepts like spatial spillover effects and spatial dependence in economic models.

- Statistical Inference in Spatial Data: Understanding hypothesis testing and confidence intervals in the context of spatial data, considering the impact of spatial autocorrelation on statistical significance.

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Software: Demonstrate proficiency in using GIS software (ArcGIS, QGIS) for data manipulation, analysis, and visualization. Practical application: Creating maps and performing spatial queries to answer research questions.

- Spatial Clustering and Outlier Detection: Learn methods for identifying clusters of similar values or outliers in spatial data, using techniques like Moran’s I and local indicators of spatial association (LISA).

- Data Visualization and Communication: Effectively communicating spatial data analysis results through clear and informative maps, charts, and graphs.

Next Steps

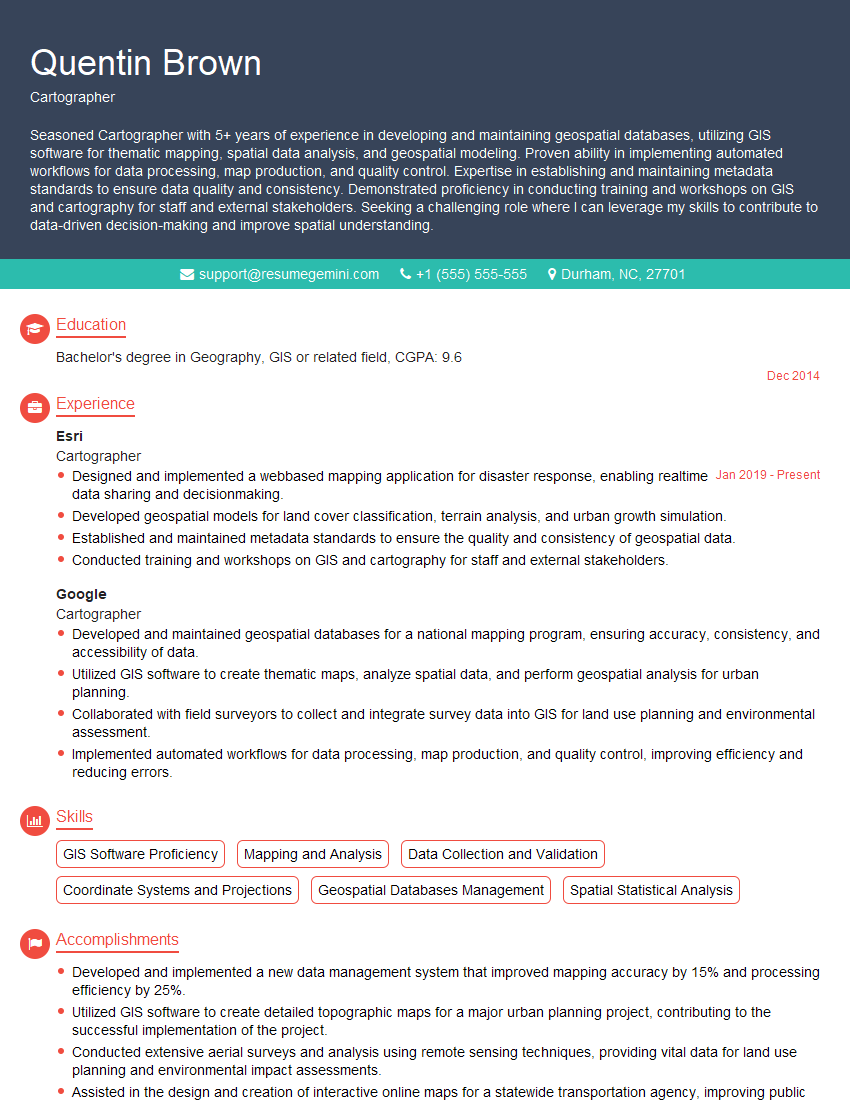

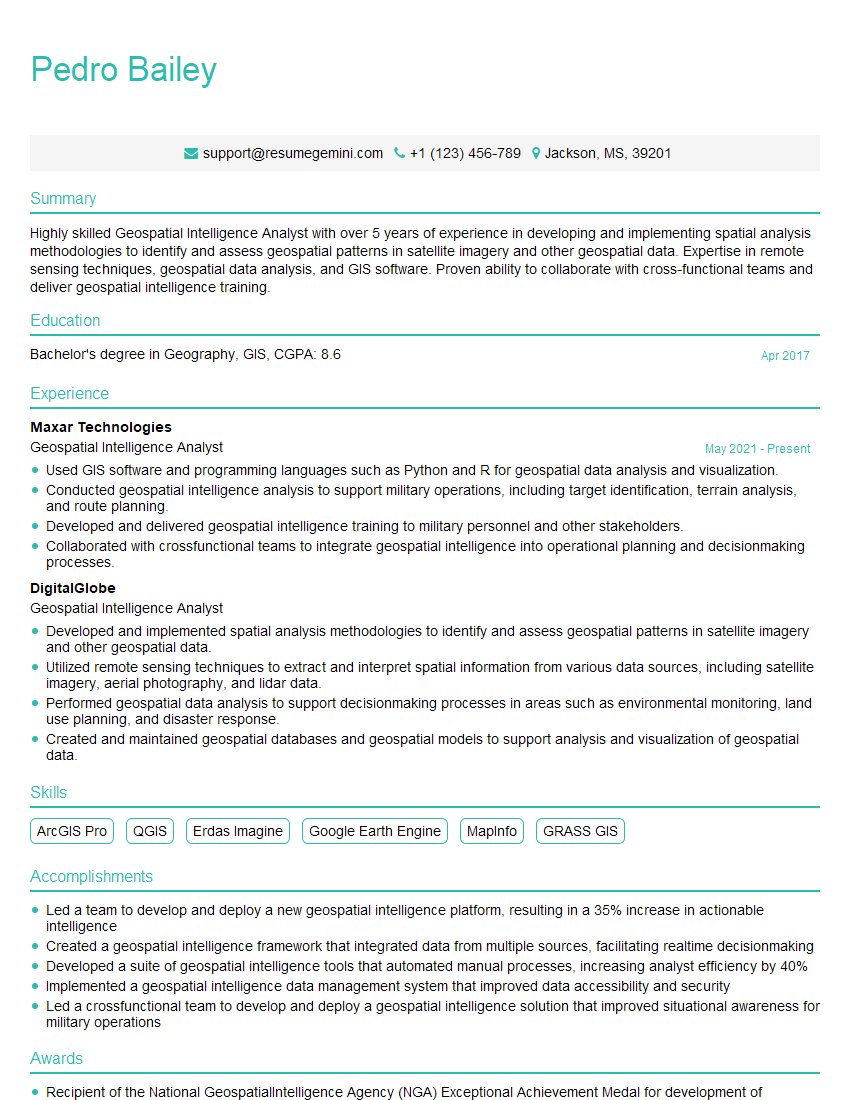

Mastering Spatial and Statistical Analysis opens doors to exciting careers in fields like urban planning, environmental science, epidemiology, and market research. To maximize your job prospects, it’s crucial to present your skills effectively. Building an ATS-friendly resume is key to getting your application noticed by recruiters. We highly recommend using ResumeGemini to craft a compelling resume that highlights your expertise in Spatial and Statistical Analysis. ResumeGemini provides you with the tools and resources, including examples of resumes tailored to this specific field, to help you create a professional and impactful document that showcases your unique qualifications. Invest time in crafting a strong resume; it’s your first impression on potential employers.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO