Unlock your full potential by mastering the most common Accessibility and Usability interview questions. This blog offers a deep dive into the critical topics, ensuring you’re not only prepared to answer but to excel. With these insights, you’ll approach your interview with clarity and confidence.

Questions Asked in Accessibility and Usability Interview

Q 1. Explain the WCAG guidelines and their importance.

WCAG, or Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, are a set of internationally recognized recommendations for making web content more accessible to people with disabilities. They’re crucial because they ensure websites and applications are usable by everyone, regardless of their abilities. Think of it like building a ramp for a wheelchair user – it doesn’t limit anyone else, but it makes a huge difference for those who need it.

WCAG is organized into four principles, each with testable success criteria:

- Perceivable: Information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive. This includes providing alternatives for non-text content (like images), using sufficient color contrast, and ensuring content is easily understandable.

- Operable: User interface components and navigation must be operable. This means ensuring all functionality is accessible via keyboard, providing enough time for users to complete tasks, and avoiding content that causes seizures.

- Understandable: Information and the operation of the user interface must be understandable. This means using clear and simple language, providing help and instructions, and ensuring the site is consistent and predictable.

- Robust: Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies. This means using valid HTML and CSS, following established coding practices, and making sure the content works with screen readers and other assistive technologies.

These guidelines are broken down into levels (A, AA, AAA), indicating the severity of each success criterion. Meeting WCAG AA is generally considered a good baseline for most websites.

Q 2. Describe your experience with assistive technologies (screen readers, etc.).

I have extensive experience with various assistive technologies, including JAWS, NVDA (NonVisual Desktop Access), VoiceOver (for macOS), and TalkBack (for Android). I’ve used them to test websites and applications from the perspective of visually impaired users. For example, I’ve used screen readers to navigate complex websites, ensuring proper heading structure, landmark identification, and effective label and form element association were implemented. I’ve also tested keyboard navigation extensively, ensuring all interactive elements could be accessed and manipulated using only the keyboard. This experience has significantly shaped my understanding of the challenges faced by users with disabilities and how to build inclusive digital experiences.

Working with these tools highlighted the importance of semantic HTML, well-structured content, and clear, concise alternative text for images and other non-text content. The experience also reinforced the critical role of proper ARIA attributes in conveying information to assistive technologies. It was eye-opening, helping me appreciate how crucial accessible design is for user experience.

Q 3. How do you conduct accessibility testing?

Accessibility testing is a multifaceted process. It’s not just about running automated tests; it requires a human-centered approach. My accessibility testing process typically involves:

- Automated testing: Using tools like WAVE, axe DevTools, and Lighthouse to identify potential violations of WCAG guidelines. These tools flag common issues like missing alt text, insufficient color contrast, and keyboard navigation problems.

- Manual testing with assistive technologies: I use screen readers, keyboard-only navigation, and other assistive technologies to evaluate the user experience directly. This involves navigating the site and verifying that content is perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust.

- Cognitive testing: Evaluating the clarity and simplicity of the information architecture, layout, and language used. I assess whether information is presented in a way that is easy to understand for users with cognitive impairments.

- Usability testing with diverse participants: I involve individuals with different types of disabilities in user testing sessions to gather feedback and identify issues not easily detected through automated or manual testing.

The key is to combine automated and manual testing, including usability testing with diverse individuals, to ensure comprehensive accessibility coverage.

Q 4. What are some common accessibility violations you’ve encountered?

Some common accessibility violations I’ve encountered include:

- Missing or insufficient alternative text for images: Screen readers rely on alt text to describe images to users. Missing or vague alt text leaves users without vital information.

- Poor color contrast: Insufficient contrast between text and background makes it difficult for users with low vision to read the content. This is a very common problem and easily fixed with sufficient color contrast.

- Lack of keyboard accessibility: Many interactive elements are not accessible using only a keyboard, excluding users who rely on keyboard navigation.

- Complex or confusing navigation: Poorly structured navigation makes it hard for users to find information, especially those with cognitive impairments.

- Missing or inadequate form labels: Screen readers rely on labels to identify form fields. Missing or unclear labels make forms difficult to use.

- Lack of semantic HTML: Using presentational elements (

,) instead of semantic elements (to,,) makes it hard for assistive technologies to interpret the content structure.

These are just a few examples; effective accessibility testing helps identify and rectify a wider range of potential problems.

Q 5. Explain the difference between usability and accessibility.

While both usability and accessibility aim to improve the user experience, they focus on different aspects. Usability focuses on making a product easy and efficient to use for *all* users. It’s about design choices that make the product intuitive and enjoyable. Accessibility, on the other hand, specifically focuses on making a product usable by people with disabilities. Think of it this way: usability is about making a product user-friendly, while accessibility is about making it *equally* user-friendly for *everyone*, including those with disabilities.

A usable product might be aesthetically pleasing and easy to navigate for most people, but it might still lack features necessary for users with visual, auditory, motor, or cognitive impairments. Accessibility ensures all these needs are met.

Q 6. How do you incorporate accessibility considerations into the design process?

Incorporating accessibility considerations throughout the design process, from the initial stages of planning to final testing, is crucial for creating truly accessible products. This requires a proactive, not reactive approach.

- Accessibility from the start: Design decisions should incorporate accessibility considerations from the outset, not as an afterthought. For example, choosing color palettes with appropriate contrast should happen during the design phase, not during development.

- Regular accessibility audits: Throughout the design and development process, regular accessibility audits should be conducted. This enables timely identification and remediation of accessibility barriers.

- Accessibility testing: Rigorous accessibility testing, using both automated and manual techniques, is essential to ensure the product meets accessibility standards.

- Collaborative approach: Collaborating with accessibility experts, users with disabilities, and assistive technology users provides valuable feedback and insights.

- Using accessibility guidelines: The design team should consistently refer to WCAG and other relevant guidelines to ensure compliance.

By integrating accessibility from the beginning, we create products that are not only inclusive but also easier to use and understand for everyone.

Q 7. Describe your experience with ARIA attributes.

ARIA (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) attributes are crucial for enhancing the accessibility of dynamic web content. They provide additional information to assistive technologies that may not be conveyed through HTML semantics alone. Think of ARIA attributes as extra hints to help assistive technologies understand complex interactive elements.

For example, consider a custom-built widget with multiple interactive parts. While HTML might structure it correctly, ARIA attributes can help screen readers identify each interactive component’s role, state, and value. For instance, using aria-label to describe a button’s function or aria-expanded to indicate whether a collapsible section is open or closed is crucial for understanding.

I’ve used ARIA attributes extensively to improve the accessibility of interactive components. My experience highlights the importance of using ARIA attributes appropriately and sparingly, avoiding the overuse of attributes which can confuse assistive technologies. It’s critical to understand when ARIA is necessary and to use it correctly according to WCAG guidelines. Incorrect implementation of ARIA can actually *reduce* accessibility.

Q 8. How do you ensure color contrast meets accessibility standards?

Ensuring sufficient color contrast is crucial for accessibility, especially for users with visual impairments like color blindness. We need to meet the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) success criteria, specifically WCAG 2.1’s Success Criterion 1.4.3 (Contrast (Minimum)). This criterion defines minimum contrast ratios between text and its background, and between graphical user interface (GUI) components and their background.

I use various tools to check contrast. For example, many browser extensions and online tools offer real-time contrast ratio calculations. I input the foreground and background colors (hex codes or RGB values) and the tool returns the ratio. WCAG recommends a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text (18pt or 14pt bold).

Example: Let’s say we have dark grey text (#333333) on a light grey background (#CCCCCC). A contrast checker would reveal this doesn’t meet the minimum requirement. We’d need to adjust either the text or background color to achieve the necessary contrast. For instance, switching to black (#000000) text would significantly improve contrast.

Beyond tools, it’s crucial to visually inspect the design with different simulated color blindness filters. This helps catch subtle contrast issues that automated tools might miss. We should aim for contrast that’s not only technically compliant but also aesthetically pleasing and easy on the eyes.

Q 9. How do you handle keyboard navigation in your designs?

Keyboard navigation is essential for users who can’t use a mouse or trackpad, whether due to motor impairments or preference. Effective keyboard navigation ensures all interactive elements are accessible via the Tab key, allowing users to navigate sequentially through the page.

I ensure logical tab order. This means that the elements should be navigable in a way that makes sense to the user, typically following a visual reading order. We avoid tab traps (where the user gets stuck in a loop) and focus traps (where the focus is trapped within a certain area and can’t be moved out of).

Example: Imagine a form with several fields. The tab order should proceed logically from the first field to the last. Using appropriate HTML elements also helps. For example, wrapping related form elements within a <fieldset> and <legend> helps structure the tabbing order and improves screen reader understanding.

Furthermore, I ensure all interactive elements receive focus visually; this could be through a change of color, border, or outline. This visual feedback is crucial for the user to understand where they currently are in the navigation process. Finally, testing keyboard navigation is an essential part of my process. I personally test it as well as using assistive technology to ensure that keyboard users can efficiently complete their tasks.

Q 10. How do you perform semantic HTML markup for accessibility?

Semantic HTML markup is fundamental for accessibility. It means using HTML elements for their intended purpose, creating a logical structure that conveys meaning to both the browser and assistive technologies like screen readers. This makes content more accessible and understandable for users with disabilities.

Examples: Instead of using a <div> for a navigation menu, I use a <nav> element. For headings, I use <h1> to <h6>, reflecting the hierarchical structure of the content. Lists should be marked up with <ul> or <ol>, and table data should be clearly structured with <thead>, <tbody>, and <tr>, <th>, and <td> elements. Using <label> elements for form inputs is also essential, creating clear association between labels and form controls and enabling users to access them with the keyboard.

A well-structured semantic HTML page improves accessibility not just for screen readers, but also for search engine optimization (SEO) and makes the code easier for developers to understand and maintain. It’s about creating a clean, logical architecture that’s usable by everyone.

Q 11. Explain your understanding of different types of disabilities and their impact on user experience.

Understanding the diverse range of disabilities is critical for creating truly inclusive designs. Disabilities impact user experience in various ways, affecting visual, auditory, motor, cognitive, and neurological functions.

- Visual impairments: Color blindness, low vision, blindness. These affect how users perceive colors, text sizes, and images. Solutions involve sufficient color contrast, alternative text for images (alt text), and options for adjusting text size.

- Auditory impairments: Deafness, hard of hearing. These affect how users process audio information. Solutions include providing captions and transcripts for videos and audio content.

- Motor impairments: Limited dexterity, tremors, paralysis. These affect users’ ability to interact with interfaces using a mouse or other pointing devices. Solutions include keyboard navigation, touch screen optimization, and alternative input methods.

- Cognitive impairments: Learning disabilities, cognitive delays. These affect users’ ability to process information, remember steps, and focus. Solutions involve clear, concise language, well-structured content, and easily scannable layouts.

- Neurological impairments: Epilepsy, autism, ADHD. These can affect users’ sensitivities to flashing animations, overwhelming layouts, and information overload. Solutions include reducing flashing content, providing clear navigation, and allowing users to control the pace and amount of information displayed.

Understanding these different challenges helps us make informed design decisions to ensure everyone can access and use our products and services equally. A design that works for someone with a disability often improves the experience for everyone.

Q 12. How do you balance accessibility with design aesthetics?

Balancing accessibility with design aesthetics is not a compromise; it’s an integration. Accessible design shouldn’t look ‘clinical’ or ‘different’; it should be seamlessly integrated into the overall aesthetic. In fact, many accessibility features enhance the user experience for everyone.

Examples: Using sufficient color contrast doesn’t mean using jarring or unpleasant color combinations. It’s about choosing color palettes thoughtfully to achieve both accessibility and visual appeal. Providing keyboard navigation doesn’t mean creating a clumsy or inconvenient interface; it means well-organized and intuitive interaction design. Using semantic HTML leads to cleaner and more maintainable code, benefiting both accessibility and development efficiency.

Often, accessible solutions improve the overall design. For example, clear headings and well-structured content not only benefit users with cognitive disabilities but also make the content more scannable and easier for everyone to understand. It’s about finding creative and elegant ways to meet accessibility requirements without sacrificing design integrity or visual appeal.

Q 13. Describe your experience with automated accessibility testing tools.

Automated accessibility testing tools are valuable but not a replacement for manual testing. Tools like WAVE, aXe, and Lighthouse can identify many accessibility issues, including broken links, missing alt text, and insufficient color contrast. They provide valuable initial insights and help catch common mistakes.

However, these tools have limitations. They can’t understand the context or intent behind the content; they may flag false positives or miss subtle issues that require human judgment. For example, an automated tool might flag a low color contrast ratio, but a human might determine that the specific use case justifies the lower ratio.

My workflow: I incorporate automated testing early in the development process. I use the results to prioritize accessibility issues and focus manual testing on the most complex aspects. Manual testing involves using assistive technologies like screen readers and evaluating the user experience from the perspective of individuals with various disabilities. Automated tools are a significant aid, offering a quick initial assessment, but comprehensive testing requires both automated and manual approaches.

Q 14. How do you address accessibility concerns from stakeholders?

Addressing accessibility concerns from stakeholders requires clear communication, education, and collaboration. Sometimes, stakeholders may prioritize aesthetics over accessibility or perceive accessibility as an added cost.

My approach: I begin by educating stakeholders about the importance of accessibility, emphasizing its legal and ethical implications. I explain how accessibility improves the overall user experience, not just for people with disabilities but for everyone. I present accessibility issues clearly and concisely, using concrete examples and avoiding technical jargon. I illustrate how accessible design can be integrated into the design process without compromising aesthetic goals.

Examples: I use data to show how inaccessible websites can lose customers and create legal risks. I demonstrate cost savings by implementing accessibility guidelines early rather than addressing issues later. I involve stakeholders in the testing process, letting them experience the challenges firsthand, which helps build consensus and understanding.

Ultimately, addressing accessibility concerns involves building a shared understanding of its value and showing how it can be a positive element of the product’s success, enhancing its reputation and expanding its potential audience.

Q 15. What are some common usability heuristics?

Usability heuristics are general principles that guide the design of user interfaces to make them more efficient and user-friendly. They aren’t strict rules, but rather guidelines to help designers make informed decisions. Jakob Nielsen’s 10 heuristics are widely recognized and form a solid foundation.

- Visibility of system status: The system should always keep users informed about what is going on, through appropriate feedback within reasonable time.

- Match between system and the real world: The system should speak the users’ language, with words, phrases and concepts familiar to the user, rather than system-oriented terms. Follow real-world conventions, making information appear in a natural and logical order.

- User control and freedom: Users often choose system functions by mistake and will need a clearly marked “emergency exit” to leave the unwanted state without having to go through an extended dialogue. Support undo and redo.

- Consistency and standards: Users should not have to wonder whether different words, situations, or actions mean the same thing. Follow platform conventions.

- Error prevention: Even better than good error messages is a careful design which prevents a problem from occurring in the first place. Either eliminate error-prone conditions or check for them and present users with a confirmation option before they commit to the action.

- Recognition rather than recall: Minimize the user’s memory load by making objects, actions, and options visible. The user should not have to remember information from one part of the dialogue to another. Instructions for use of the system should be visible or easily retrievable whenever appropriate.

- Flexibility and efficiency of use: Accelerators — unseen by the novice user — may often speed up the interaction for the expert user such that the system can cater to both inexperienced and experienced users. Allow users to tailor frequent actions.

- Aesthetic and minimalist design: Dialogues should not contain information which is irrelevant or rarely needed. Every extra unit of information in a dialogue competes with the relevant units of information and diminishes their relative visibility.

- Help users recognize, diagnose, and recover from errors: Error messages should be expressed in plain language (no codes), precisely indicate the problem, and constructively suggest a solution.

- Help and documentation: Even though it is better if the system can be used without documentation, it may be necessary to provide help and documentation. Any such information should be easy to search, focused on the user’s task, list concrete steps to be carried out, and not be too large.

For example, a poorly designed form might violate the ‘consistency and standards’ heuristic by using different labels for the same type of input field on different pages.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. How do you conduct user research for accessibility?

User research for accessibility involves understanding the needs and limitations of users with disabilities. This requires a multi-faceted approach.

- Participant Recruitment: Crucially, recruit participants representing a diverse range of disabilities (visual, auditory, motor, cognitive). Don’t rely solely on self-reported disabilities; consider using assistive technologies during testing.

- Methods: Employ a combination of methods. Think-aloud protocols are valuable to understand users’ thought processes. Usability testing with screen readers, keyboard navigation, and alternative input devices (switch controls, eye tracking) provides direct insight into accessibility issues. Surveys and interviews can gather broader perspectives and context.

- Accessibility Guidelines: Always test against WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) success criteria. This ensures you’re addressing key accessibility standards.

- Observe and Analyze: Pay close attention to users’ struggles. Where do they get stuck? What assistive technology are they using, and how effectively does it work with your design?

- Iterate and Improve: User research is iterative. Based on findings, redesign and retest. Accessibility is an ongoing process, not a one-time fix.

For example, in a recent project, we observed a user with low vision struggling to distinguish between form elements due to poor color contrast. This led us to redesign the form using higher contrast colors and larger font sizes.

Q 17. Describe your experience with creating accessible forms.

Creating accessible forms requires meticulous attention to detail. My experience involves ensuring all aspects of the form are usable by people with disabilities.

- Semantic HTML: Using appropriate HTML5 elements (

,,, etc.) ensures screen readers can correctly interpret the form’s structure and content. - Clear and Concise Labels: Every input field must have a clear and concise label associated with it using the

forattribute on labels andidattributes on input fields to link the label to the correct input. Avoid ambiguous or shortened labels. - Appropriate Input Types: Using the correct input types (

email,number,date) improves usability and allows for input validation. This helps screen readers and assistive technologies provide relevant context. - Error Handling: Provide clear and descriptive error messages, focusing on how to correct the issue. Avoid using generic messages like “Invalid input.”

- Keyboard Navigation: Ensure all form elements are accessible using only the keyboard. Tab order should be logical and intuitive.

- ARIA Attributes: If needed, ARIA attributes can supplement HTML to improve accessibility for complex form elements (e.g.,

aria-describedbyto link error messages to inputs). - Color Contrast: Maintain sufficient color contrast between text and background to ensure readability.

For instance, I once redesigned a complex multi-step registration form, moving from a confusing visual design to a clear, logical structure using proper semantic HTML and ARIA attributes. This dramatically improved usability for everyone, including users relying on screen readers.

Q 18. How do you ensure your designs are accessible on different devices?

Designing for accessibility across different devices requires a responsive design approach that adapts to various screen sizes, resolutions, and input methods.

- Responsive Design Principles: Use a fluid grid system and flexible images to ensure content adapts to different screen sizes. Avoid fixed-width layouts that might break on smaller devices.

- Touch-Friendly Interactions: Design for touch interactions, ensuring elements are large enough to be easily tapped. Avoid small buttons or links that are difficult to select on touchscreens.

- Media Queries: Use CSS media queries to adjust styles for different screen sizes and orientations. This ensures consistent presentation and usability across devices.

- Testing on Diverse Devices: Test your design on a wide range of devices, including smartphones, tablets, and laptops, to identify potential accessibility issues.

- Progressive Enhancement: Build your site to work gracefully for users with older or less capable devices. This often means a focus on core functionality initially, enhanced with more advanced features where appropriate.

- Consider Assistive Technologies: Evaluate your website’s accessibility not only on various device types but also with assistive technologies such as screen readers and voice control systems.

In a recent project, I ensured our website was accessible on various devices by implementing a responsive design, using larger touch targets, and meticulously testing on different screen sizes and browsers, along with assistive technology testing.

Q 19. How do you measure the success of your accessibility efforts?

Measuring the success of accessibility efforts involves a multi-pronged approach, combining qualitative and quantitative data.

- Usability Testing: Conduct regular usability testing with people with disabilities to identify remaining accessibility barriers. This is crucial for continuous improvement.

- Automated Testing: Use automated accessibility testing tools (like WAVE, Lighthouse, axe DevTools) to identify potential issues early in the development cycle. Note these are only initial checks.

- WCAG Conformance: Aim for WCAG conformance, using the guidelines as a benchmark for success. Document your progress and remaining work.

- User Feedback: Collect feedback through surveys, contact forms, or user interviews to gauge user satisfaction with accessibility features.

- Metrics: Track metrics such as the number of accessibility issues fixed, the percentage of WCAG conformance, and user satisfaction scores related to accessibility.

- Accessibility Audits: Periodically conduct formal accessibility audits to ensure that ongoing development aligns with your goals.

For instance, in one project, we tracked the number of accessibility bugs resolved over time, and this data, along with improved usability testing scores, demonstrated our progress toward enhanced accessibility.

Q 20. What are some common challenges you face when implementing accessibility?

Implementing accessibility often presents challenges, including:

- Time and Resource Constraints: Accessibility often requires extra time and resources, which can be a barrier for projects with tight deadlines or limited budgets.

- Technical Complexity: Addressing complex accessibility issues can require specialized knowledge and skills. Developers may not always have the necessary expertise.

- Lack of Awareness and Buy-in: Sometimes, there’s a lack of awareness or understanding of the importance of accessibility, leading to inadequate prioritization.

- Maintaining Accessibility Over Time: Accessibility is not a one-time fix. As designs and technologies change, ongoing maintenance and updates are needed to ensure accessibility is maintained.

- Conflicting Priorities: Balancing accessibility with other design and development priorities can be a challenge, requiring careful planning and prioritization.

- Testing limitations: Thoroughly testing for all types of accessibility issues can be complex and difficult to do thoroughly, especially with a lack of adequate resources.

One common strategy to overcome these challenges is to integrate accessibility considerations early in the design process, rather than treating it as an afterthought. Educating stakeholders about the importance of accessibility is also crucial.

Q 21. Describe your experience with creating accessible PDFs.

Creating accessible PDFs requires careful attention to both content creation and document structure.

- Use of Accessible Software: Use software designed for creating accessible documents, such as Microsoft Word or LibreOffice Writer. Ensure proper tagging.

- Logical Structure and Tags: Organize the PDF with headings, lists, tables, and other structural elements. Use appropriate tags to indicate the purpose and function of each element. Screen readers rely on this structure to interpret the document’s content.

- Alternative Text for Images: Provide descriptive alternative text (alt text) for all images to convey the image’s meaning to users who can’t see it.

- Table Structure: Use tables correctly, with header rows and column headers, so screen readers can properly interpret tabular data.

- Color Contrast: Ensure sufficient color contrast between text and background to ensure readability.

- Font Choice: Select fonts that are easy to read, and avoid using decorative fonts that may be difficult to render for users with visual impairments.

- Document Accessibility Checker: Use the built-in accessibility checkers (like in Adobe Acrobat) to identify and fix potential issues.

- Linear Reading Order: Ensure the reading order is logical and consistent with the document’s visual layout. Incorrect reading order can create confusion for screen reader users.

I have extensive experience using accessibility checkers in Adobe Acrobat to ensure PDFs meet accessibility requirements, including proper tagging, descriptive alternative text, and proper linear reading order. For complex documents, I often collaborate with subject matter experts to guarantee that the accessibility of the document matches its complexity.

Q 22. How do you stay updated on the latest accessibility standards and best practices?

Staying current in the ever-evolving field of accessibility requires a multi-pronged approach. I actively participate in online communities, such as those on accessibility mailing lists and forums, engaging with other professionals and learning from shared experiences and best practices. I regularly attend webinars and conferences focused on accessibility, often presented by leading experts and organizations like the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium). Furthermore, I subscribe to newsletters and follow key influencers on social media who share updates on new standards, techniques, and emerging technologies. Finally, I meticulously review updates to WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) and other relevant guidelines, ensuring my knowledge aligns with the latest recommendations.

For example, I recently attended a webinar on accessible AI, which significantly broadened my understanding of how to design inclusive interfaces for voice assistants and other AI-powered systems. This continuous learning cycle is critical in ensuring I deliver cutting-edge, accessible solutions.

Q 23. What is your experience with accessibility compliance regulations?

My experience with accessibility compliance regulations is extensive. I’ve worked with various legal frameworks, including the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the US and the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) in Canada. I understand the importance of Section 508 compliance in the US federal government context. I’m familiar with the nuances of these regulations, knowing that the legal landscape is complex and often requires careful interpretation. I’m adept at translating these broad requirements into actionable steps during the design and development process. This includes working with legal teams to ensure compliance and proactively mitigating risks.

For instance, in a recent project, we navigated the complexities of ADA compliance for a public-facing website, ensuring it met the criteria for screen reader compatibility, keyboard accessibility, and appropriate color contrast. We developed a detailed accessibility statement and implemented comprehensive testing procedures to demonstrate our commitment to accessibility.

Q 24. How do you involve users with disabilities in the design process?

User involvement is paramount in creating truly accessible designs. I believe in employing a user-centered design approach where individuals with disabilities are actively involved throughout the design process. This includes conducting user research through interviews, focus groups, and usability testing sessions with diverse participants representing various disabilities. This enables direct feedback and ensures that the solutions are not only technically compliant but also genuinely usable and beneficial to the intended audience.

For example, during a project involving the redesign of a mobile banking app, we conducted usability testing sessions with visually impaired users, employing screen readers and other assistive technologies. Their feedback led to significant improvements in the navigation structure, labelling of interactive elements, and overall usability of the app. This direct engagement ensures the design solutions are user-validated and address actual user needs.

Q 25. Explain your understanding of accessible multimedia content.

Accessible multimedia content goes beyond simply providing captions or transcripts. It involves ensuring that all aspects of the content are perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust (POUR). This means providing alternative text for images, transcripts for audio, and captions for videos. Furthermore, it involves using appropriate file formats, ensuring that the content is compatible with assistive technologies, and avoiding flashing or seizure-inducing content. Multimedia content should be structured logically so that assistive technologies can interpret and present the information effectively.

For instance, when creating an instructional video, we ensure that the captions are accurate and timed appropriately. We also provide a full transcript, which users can download or read along with the video. We use descriptive audio for videos lacking visuals, and we ensure images are described accurately with alternative text. We also carefully consider the color contrast to make sure the visuals are accessible to those with visual impairments.

Q 26. Describe your experience working with developers to implement accessibility solutions.

Collaborating effectively with developers is key to successful accessibility implementation. I foster a collaborative relationship by providing clear, concise specifications, often including detailed documentation with examples and specific accessibility requirements. I leverage accessibility testing tools to highlight potential issues during development. I regularly participate in code reviews, actively examining the code for accessibility best practices. Clear communication is essential, ensuring everyone understands the ‘why’ behind the accessibility guidelines and the importance of incorporating accessibility from the start of the development lifecycle, rather than treating it as an afterthought.

For example, I’ve successfully worked with development teams to integrate ARIA attributes (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) into custom JavaScript components, enhancing their accessibility for screen reader users. I also frequently use developer tools to identify and resolve issues with keyboard navigation and proper semantic HTML markup.

Q 27. How do you handle accessibility issues discovered after launch?

When accessibility issues are discovered post-launch, a systematic approach is crucial. First, we prioritize the issues based on severity and impact, leveraging user feedback and accessibility testing tools to identify the most critical problems. We then develop and implement fixes, employing agile methodologies to rapidly address the most pressing concerns. This often involves close collaboration with developers, QA, and product owners to ensure a quick turnaround while maintaining code quality. We also communicate transparently with users, acknowledging the issue and providing updates on the progress of the fix.

For example, if we discovered a navigation issue impacting screen reader users, we would prioritize this fix immediately, deploying a hotfix as soon as possible. We’d then monitor user feedback to ensure the fix was effective and address any remaining concerns.

Q 28. What is your process for prioritizing accessibility fixes?

Prioritizing accessibility fixes requires a thoughtful process. We generally use a risk-based approach. We consider factors such as the severity of the issue (e.g., blocking functionality vs. minor cosmetic issue), the number of users affected, and the potential legal implications. The impact on user experience also plays a key role. We might use a matrix, assigning weights to these factors to create a ranked list of priorities. This allows us to focus our resources on fixing the most significant issues first while still tracking and addressing less critical ones over time. Regular accessibility audits and ongoing user feedback inform this prioritization process.

For example, a screen reader incompatibility affecting the core functionality of a website would be prioritized higher than a minor color contrast issue on a less-critical page.

Key Topics to Learn for Accessibility and Usability Interview

- Understanding WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines): Learn the principles and success criteria of WCAG, focusing on levels A, AA, and AAA. Consider how these guidelines translate into practical design and development choices.

- Assistive Technology (AT) Familiarity: Explore different types of AT (screen readers, keyboard navigation, switch controls) and how they interact with web interfaces. Practice navigating websites using a screen reader to understand user experience from a different perspective.

- Usability Testing Methods: Master various usability testing methodologies, including heuristic evaluation, cognitive walkthroughs, and user interviews. Understand how to apply these methods to identify accessibility and usability issues.

- Inclusive Design Principles: Familiarize yourself with inclusive design principles, such as considering diverse users, avoiding assumptions, and building flexibility into your designs. Learn how to apply these to create accessible and usable products for everyone.

- Accessibility Auditing & Remediation: Learn how to conduct accessibility audits using automated tools and manual testing techniques. Understand how to effectively remediate identified accessibility issues in web applications and designs.

- ARIA (Accessible Rich Internet Applications): Understand the role of ARIA attributes in enhancing the accessibility of dynamic content and complex web components. Practice implementing ARIA attributes correctly to improve the user experience for assistive technology users.

- Color Contrast & Visual Design: Learn about color contrast ratios and their importance for readability. Explore best practices for visual design that accommodates users with visual impairments.

- Form Design & Accessibility: Understand how to design accessible forms that are easy to use for everyone, including those with motor impairments or cognitive disabilities. Focus on clear labeling, proper input types, and error handling.

Next Steps

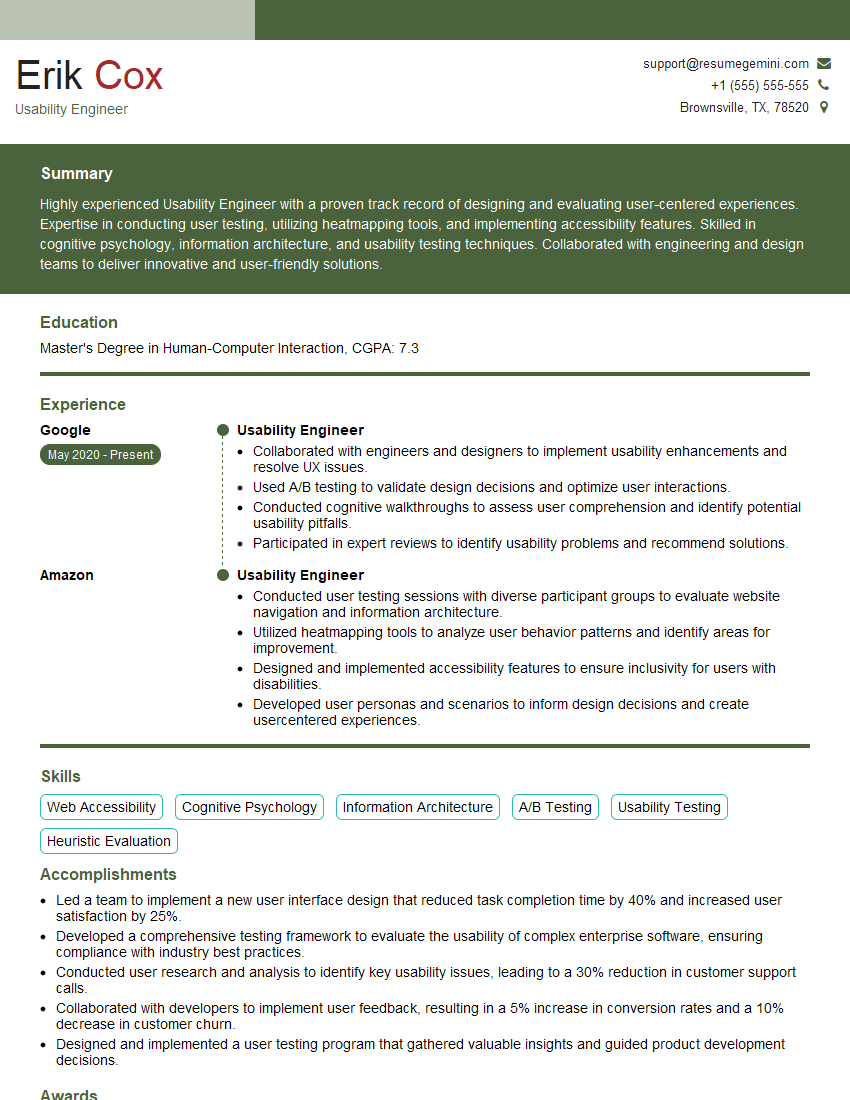

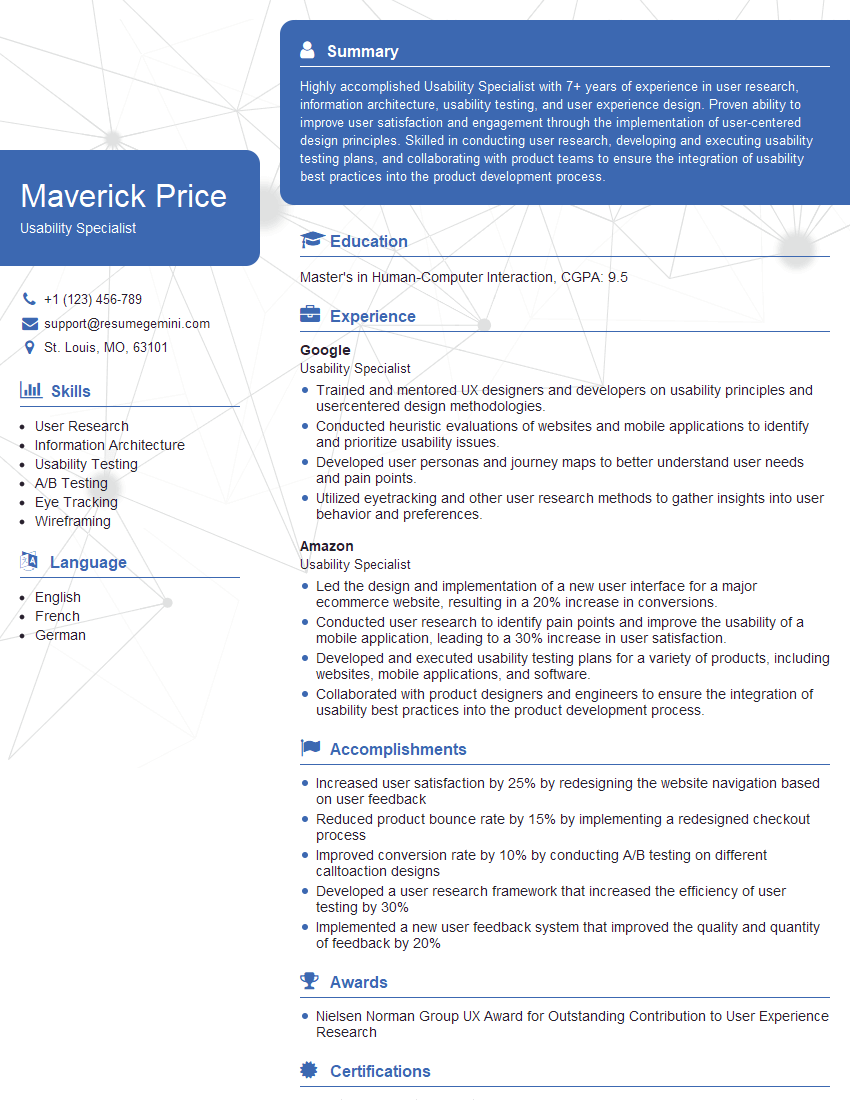

Mastering Accessibility and Usability is crucial for career advancement in today’s inclusive digital landscape. Employers highly value candidates who understand how to create accessible and usable products for diverse user groups. To significantly boost your job prospects, create an ATS-friendly resume that highlights your skills and experience effectively. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource to help you build a professional and impactful resume. We provide examples of resumes tailored to Accessibility and Usability roles to help you get started. Invest the time in crafting a compelling resume; it’s your first impression on potential employers.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO