Unlock your full potential by mastering the most common Adjustment Computations interview questions. This blog offers a deep dive into the critical topics, ensuring you’re not only prepared to answer but to excel. With these insights, you’ll approach your interview with clarity and confidence.

Questions Asked in Adjustment Computations Interview

Q 1. Explain the concept of least squares adjustment.

Least squares adjustment is a powerful mathematical technique used to find the best-fitting solution to an overdetermined system of equations. In surveying, this means finding the most probable values for unknown parameters (like coordinates) given a set of observations (like distances and angles) that contain errors. Imagine you’re trying to fit a straight line through a scatter plot of points – least squares finds the line that minimizes the sum of the squared vertical distances between the points and the line. Similarly, in surveying, it minimizes the sum of the squared errors in the observations. This ‘best fit’ is statistically optimal under certain assumptions (which we’ll discuss later).

The process involves setting up a system of equations that relate the observations to the unknowns. Because we have more observations than unknowns (overdetermined system), these equations are usually inconsistent. Least squares adjustment solves this by finding corrections to the observations that minimize the sum of the squared residuals (the differences between the observed values and the adjusted values). These corrections are then used to compute the best estimates of the unknown parameters.

Q 2. What are the different types of errors encountered in surveying?

Errors in surveying can be broadly categorized into two types: systematic and random.

- Systematic Errors: These are errors that follow a pattern or trend. They are caused by factors like instrument malfunction (e.g., a poorly calibrated theodolite consistently measuring angles incorrectly), environmental conditions (e.g., temperature affecting tape measurements), or personal biases (e.g., consistently misreading a scale). Systematic errors are predictable and can often be corrected or eliminated through careful planning and calibration.

- Random Errors: These are unpredictable errors that occur due to various unknown causes. They are inherently present in any measurement process. Examples include slight variations in reading a scale, minor vibrations affecting the instrument, and unpredictable atmospheric changes. Random errors follow a statistical distribution (often assumed to be normal) and cannot be completely eliminated, but their effects can be minimized through repeated measurements and statistical analysis.

In addition to these, we also encounter blunders (also known as gross errors), which are mistakes made during the measurement process, such as reading the wrong value or making a calculation error. These are significantly larger than random or systematic errors and need to be identified and corrected separately.

Q 3. Describe the process of error propagation in adjustment computations.

Error propagation describes how errors in the input measurements affect the accuracy of the computed results. Imagine you’re calculating the area of a rectangle using measured lengths and widths. Even small errors in those measurements will propagate to the calculated area, leading to uncertainty in the final result. The same principle applies to adjustment computations.

In least squares adjustment, error propagation is quantified using the covariance matrix. The covariance matrix summarizes the uncertainties and correlations between the adjusted parameters. The elements of the covariance matrix are derived from the variance-covariance matrix of the observations (which reflects the precision of the measurements) and the design matrix (which describes the relationship between the observations and the unknowns). Error propagation analysis allows us to assess the reliability of the adjusted results and quantify the uncertainties associated with them. This is crucial for determining the quality of the survey and ensuring the accuracy of the final products.

Q 4. How do you handle blunders in adjustment computations?

Handling blunders is critical as they can significantly bias the results of least squares adjustment. The first step is detection. Blunders are often detected by visual inspection of the data, looking for outliers or values that are significantly different from other observations. Statistical tests, such as outlier detection methods based on studentized residuals, can also be employed. Once a blunder is detected, it needs to be identified (pinpointing the source of error) and then corrected. This might involve re-measurement, review of field notes, or even elimination of the erroneous data point, depending on the circumstances. It is important to document all the steps taken in blunder detection, identification, and correction to maintain the integrity of the adjustment process.

Robust estimation methods can improve the resilience of the adjustment to the presence of outliers. These methods assign less weight to data points that appear to be outliers, reducing their influence on the final solution. Examples include least absolute deviations (LAD) and M-estimators, offering more robust alternatives to standard least squares in situations where blunders might be present.

Q 5. What are the assumptions underlying least squares adjustment?

The least squares adjustment relies on several key assumptions:

- Observations are normally distributed: The random errors in the observations follow a normal (Gaussian) distribution. This is a crucial assumption that allows us to use statistical tests and estimate confidence intervals.

- Errors have zero mean: The average of the random errors is zero. This implies that there is no systematic bias in the observations.

- Errors are uncorrelated: The errors in different observations are independent of each other. This means that the error in one measurement doesn’t influence the error in another.

- Weights reflect the precision of observations: The weight assigned to each observation is inversely proportional to its variance (a measure of its precision). More precise measurements get higher weights.

It’s important to understand that these are idealizations. In reality, these assumptions might not be perfectly met. However, least squares is quite robust to mild violations of these assumptions. Significant deviations may necessitate the use of more sophisticated adjustment techniques.

Q 6. Explain the difference between weighted and unweighted least squares.

The difference between weighted and unweighted least squares lies in how the observations are treated. In unweighted least squares, all observations are given equal importance. This is appropriate when the observations have similar precision. However, in weighted least squares, each observation is given a weight that reflects its relative precision. More precise observations (those with smaller variances) get higher weights, meaning they influence the adjusted values more strongly.

For example, suppose you have distance measurements made with different precision instruments. A measurement from a high-precision total station would receive a higher weight than a measurement from a less precise tape. Weighted least squares accounts for this difference in precision, leading to a more statistically accurate adjustment. In essence, weighted least squares provides a more sophisticated and reliable solution when the precision of observations varies significantly. Unweighted least squares is a special case of weighted least squares where all weights are equal to 1.

Q 7. How do you determine the weight matrix in a least squares adjustment?

The weight matrix in a least squares adjustment reflects the precision of the observations. It’s a diagonal matrix (meaning only diagonal elements are non-zero) where the diagonal elements represent the weights of the individual observations. These weights are typically inversely proportional to the variances of the observations. That is, a smaller variance (indicating higher precision) results in a larger weight.

Determining the weight matrix requires understanding the sources of error in each observation type. This is often based on the specifications of the measuring instrument, the environmental conditions during measurement, and the experience of the surveyor. For example, if the standard deviation of repeated distance measurements with a total station is known to be 2 mm, the corresponding weight would be inversely proportional to the square of this standard deviation. The weight matrix is often expressed as a function of the variance-covariance matrix of the observations, with the inverse of this matrix providing the weight matrix for the adjustment calculation.

Q 8. What is the significance of the covariance matrix in adjustment computations?

The covariance matrix is fundamental in adjustment computations because it encapsulates the uncertainties and correlations between observations. Imagine you’re measuring the sides of a triangle; each measurement has some inherent error. The covariance matrix tells us not only how much each measurement varies individually (its variance, represented on the diagonal), but also how much the errors in different measurements are related (covariance, off-diagonal elements). A large covariance between two measurements indicates they are strongly correlated; their errors tend to move together. This information is crucial for generating a statistically sound and reliable adjustment solution, allowing us to optimally weight observations based on their precision and interdependencies. In a least squares adjustment, the inverse of the covariance matrix (the weight matrix) guides the minimization process, ensuring measurements with higher precision receive more emphasis.

For example, if we’re using GPS data for surveying, satellite signals from different satellites may be correlated due to atmospheric effects. The covariance matrix would reflect these correlations, improving the accuracy of our position calculations compared to treating the observations as independent.

Q 9. Explain the concept of redundancy in adjustment computations.

Redundancy in adjustment computations refers to the presence of more observations than the minimum necessary to solve for the unknowns. Think of it like having multiple witnesses to an event – each provides information, and the overlap allows for error detection and a more robust solution. Redundancy improves the reliability of the adjustment by providing a check on the consistency of the observations. It allows us to detect blunders (gross errors) and assess the precision of the adjusted parameters. The more redundant observations, the better we can identify and handle errors.

For instance, if we need to determine the coordinates of a point using distance measurements, having more than the minimum number of distances increases redundancy. If one distance measurement is significantly off (a blunder), the redundant observations allow us to identify and mitigate the influence of this erroneous measurement. The redundancy allows us to statistically assess the quality of the adjusted parameters.

Q 10. How do you assess the quality of an adjustment solution?

Assessing the quality of an adjustment solution involves several key aspects:

- Goodness-of-fit: This is measured using statistical tests like the chi-squared test to determine if the observations are consistent with the assumed error model. A poor goodness-of-fit may indicate systematic errors or incorrect assumptions about the observation errors.

- Precision of the adjusted parameters: This is quantified by the variance-covariance matrix of the adjusted parameters. Smaller variances indicate higher precision.

- Residuals analysis: Examining the residuals (differences between observed and adjusted values) can reveal patterns or outliers that suggest problems with the data or the adjustment model. Large residuals warrant investigation.

- Detection of outliers: Outliers are observations that deviate significantly from the general pattern. Their presence can degrade the quality of the adjustment significantly, thus their detection and handling are crucial.

A high-quality adjustment solution exhibits a good goodness-of-fit, high precision of the adjusted parameters, and absence of significant outliers in the residuals.

Q 11. Describe the process of outlier detection in adjustment computations.

Outlier detection in adjustment computations is critical for obtaining reliable results. Several methods exist; some common ones include:

- Data snooping: This involves visually inspecting the residuals. Large residuals, exceeding a certain threshold (often based on a multiple of the standard deviation), are flagged as potential outliers.

- Statistical tests: Tests like the studentized residual test or Dixon’s test can provide a more formal assessment of whether a residual is significantly different from the others.

- Robust estimation techniques: These methods, such as Least Median of Squares (LMS) or Least Trimmed Squares (LTS), are less sensitive to outliers than traditional least squares. They minimize the influence of outliers on the adjustment solution.

Once identified, outliers require careful consideration. Investigate the potential cause (measurement error, data entry mistake, etc.). If a valid cause is found, the outlier may be removed or corrected. If no cause is apparent, it may be necessary to re-evaluate the data or the adjustment model.

Q 12. What are the different methods for solving normal equations in least squares adjustment?

Solving the normal equations, central to least squares adjustment, can be done using various methods:

- Direct methods: These methods directly solve the system of equations. Examples include Gauss elimination, Cholesky decomposition, and LU decomposition. They’re efficient for smaller systems but can become computationally expensive for very large datasets.

- Iterative methods: These methods approximate the solution through successive iterations. Examples include Gauss-Seidel and conjugate gradient methods. They are particularly suitable for large, sparse systems where direct methods are impractical.

- Matrix inversion: Though conceptually straightforward, direct matrix inversion is computationally inefficient and less numerically stable compared to the other methods. It’s generally avoided in large-scale adjustment problems.

The choice of method depends on factors such as the size and structure of the normal equations and computational resources.

Q 13. Explain the concept of condition equations in adjustment computations.

Condition equations, also known as constraint equations, represent relationships that must hold between observations or parameters in an adjustment. They express geometric or physical constraints of the problem, ensuring the solution satisfies these known relationships. For instance, in a triangulation network, condition equations might enforce the closure of triangles (the sum of angles should equal 180 degrees). They’re crucial for incorporating prior information or geometric constraints into the adjustment. Condition equations improve the quality and stability of the adjustment solution by eliminating some unknowns or fixing some parameters to known values.

Imagine surveying a closed traverse. Condition equations would ensure the sum of the angles equals (n-2) * 180 degrees, reflecting the geometric constraint of a closed polygon. Including these equations avoids inconsistencies arising from accumulated measurement errors.

Q 14. How do you handle correlated observations in adjustment computations?

Correlated observations are those whose errors are not independent; the error in one observation influences the error in others. Ignoring correlation leads to biased and inefficient adjustment solutions. To handle correlated observations, we must use the full covariance matrix (not just the diagonal of variances) in the adjustment. This matrix correctly represents the variances and covariances of the observations. The inverse of this covariance matrix (the weight matrix) is then used in the least squares solution. The weight matrix appropriately weights the observations, considering their precision and interdependence.

Using GPS observations as an example, the signals from nearby satellites can be correlated due to shared atmospheric effects. Failing to account for this correlation in the position adjustment will lead to an inaccurate and over-optimistic estimate of the position precision.

Q 15. What is the difference between a parametric and a non-parametric adjustment?

The core difference between parametric and non-parametric adjustments lies in how they handle the unknowns. Parametric adjustments assume a specific mathematical model, defining the relationship between observations and unknowns. Think of it like fitting a curve to data points – you assume the curve follows a particular equation (the model), and the adjustment process finds the best-fitting parameters (unknowns) of that equation. Non-parametric adjustments, on the other hand, don’t rely on a predefined model. They focus on the spatial relationships between the observations directly, often using techniques like smoothing or interpolation to resolve inconsistencies. Imagine trying to connect irregularly spaced points on a map – a non-parametric approach might focus on minimizing the overall distance between connected points without assuming any particular underlying function.

- Parametric: Uses a mathematical model (e.g., least squares adjustment) to estimate unknowns based on observations. Suitable for situations where a well-defined model exists, offering higher precision.

- Non-parametric: Doesn’t rely on a specific model. More flexible for irregularly spaced data or situations with complex relationships but may offer slightly lower precision.

For instance, adjusting a level network using height differences as observations is a classic example of a parametric adjustment, as we assume a simple linear relationship between the heights. Conversely, adjusting point clouds from a LiDAR scan might leverage a non-parametric method if the data is very dense and complex, making the assumption of a specific model difficult.

Career Expert Tips:

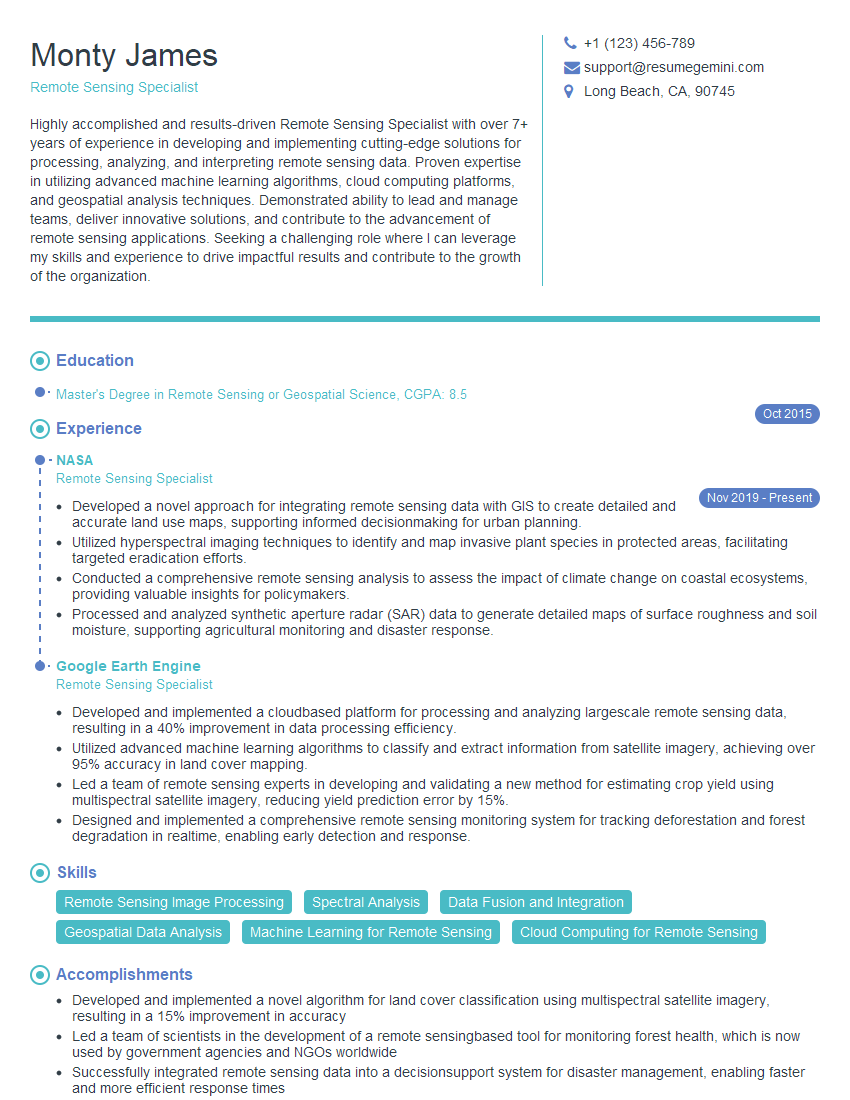

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Describe the application of adjustment computations in GPS surveying.

Adjustment computations are absolutely crucial in GPS surveying for several reasons. GPS receivers provide noisy and redundant measurements – meaning there are more measurements than needed to determine the coordinates – due to atmospheric effects, multipath errors, and receiver limitations. Adjustment techniques are used to reconcile these discrepancies and obtain the most probable coordinates for surveyed points. This involves employing methods like least squares to minimize the errors and produce a consistent, optimal solution.

Specifically, GPS data adjustments handle:

- Coordinate transformation: GPS coordinates are typically in a geocentric system. Adjustment methods transform these to local coordinate systems, simplifying integration with existing surveys.

- Error mitigation: Adjustments account for errors in satellite ephemeris data, atmospheric delays, and receiver clock biases, improving the accuracy of position determination.

- Network adjustment: When multiple GPS receivers observe common points, a network adjustment accounts for all observations simultaneously, yielding more robust and accurate results than individual point processing.

Imagine a large construction project where precise coordinates are essential. The use of adjustment computations ensures that the GPS data informs accurate positioning and contributes to a cohesive design and construction process. Without it, accumulated small errors in GPS measurements could lead to substantial inaccuracies in the final structure.

Q 17. How do you adjust a network of GPS observations?

Adjusting a network of GPS observations typically involves a least squares adjustment. The process involves several steps:

- Data Preparation: Collect GPS observations (pseudoranges or carrier phase measurements) from multiple receivers at various points. Check the data for outliers or gross errors.

- Model Formulation: Establish a mathematical model that relates the observations (pseudoranges/carrier phases) to the unknown coordinates of the GPS points. This usually involves considering satellite positions, atmospheric delays, receiver clock errors, and other potential error sources.

- Least Squares Solution: Apply a least squares adjustment algorithm to find the most probable estimates for the unknown coordinates that minimize the weighted sum of the squared residuals (differences between observed and computed values). Software packages like GeoMAGIC or commercial surveying software perform this computationally intensive task.

- Quality Control: Assess the quality of the adjustment by evaluating the residuals and statistical measures like variance-covariance matrices. This helps to identify potential outliers or model inadequacies.

- Coordinate Transformation (Optional): Transform the estimated coordinates from the GPS reference system (e.g., WGS84) to a local datum or map projection, ensuring compatibility with existing survey data.

For example, a network adjustment might involve several base stations and roving receivers measuring distances and angles between these. Using a least squares algorithm, the most likely positions of all points in the network can be computed, giving a cohesive network of interconnected survey markers.

Q 18. Explain the concept of datum transformation in adjustment computations.

Datum transformation is a crucial step in adjustment computations, especially when dealing with data from different coordinate systems. A datum defines a coordinate system’s origin, orientation, and the underlying ellipsoid model representing the Earth’s shape. Different datums exist due to various approaches to approximating the Earth’s geoid (the equipotential surface of gravity). Transforming coordinates between datums ensures compatibility between datasets from diverse sources.

Common methods include:

- Helmert Transformation (7-parameter transformation): This is a widely used method that uses three translations, three rotations, and a scale factor to transform coordinates between datums.

- Molodensky-Badekas Transformation: This method is particularly suitable for cases where only a limited number of control points with known coordinates in both datums are available.

Consider a scenario where you need to integrate data from an old survey using a local datum with a new GPS survey in WGS84. A datum transformation is necessary before performing any further adjustments to ensure the data is consistent and suitable for analysis or integration. The lack of this step could introduce significant inaccuracies in the final results.

Q 19. How do you adjust photogrammetric measurements?

Photogrammetric measurements, obtained from overlapping aerial or terrestrial images, require adjustment to create an accurate and consistent 3D model. This adjustment accounts for image distortions, measurement errors, and the geometry of image acquisition. The process often involves a bundle adjustment, a sophisticated least squares technique.

Bundle adjustment optimizes the positions of the cameras (orientation parameters such as exterior orientation elements) and the three-dimensional coordinates of the points (object points) simultaneously, minimizing the reprojection errors. Reprojection error is the distance between the measured image coordinates and the coordinates predicted by the model.

The steps usually involve:

- Image orientation: Establishing the relative and absolute orientation of the images.

- Point measurement: Identifying corresponding points (tie points) in overlapping images.

- Bundle adjustment: Using a least squares algorithm to optimize camera positions and 3D point coordinates.

- Error analysis: Assessing the accuracy and consistency of the resulting 3D model.

Imagine creating a 3D model of a building from aerial photographs. Bundle adjustment helps eliminate distortions caused by camera lens and aircraft movements, producing a very accurate and geometrically consistent model. It’s essential for applications such as city modeling, construction, and disaster assessment.

Q 20. Describe the use of adjustment computations in cadastral surveying.

Adjustment computations are fundamental in cadastral surveying, which deals with the definition, demarcation, and recording of land boundaries. The accuracy of land boundaries directly affects property rights and economic transactions, making precise measurements and adjustments essential.

Common applications include:

- Boundary demarcation: Adjusting measurements from different survey techniques (e.g., GPS, total station, traditional methods) to create a consistent and accurate representation of land parcels.

- Area calculation: Ensuring accurate calculation of land areas based on adjusted coordinates.

- Error propagation analysis: Assessing the impact of measurement errors on the overall accuracy of boundary definition.

- Network adjustment: Creating a consistent geometric network of control points and boundary markers for a region.

For example, imagine surveying a piece of land using GPS and total stations. An adjustment process would reconcile any discrepancies between the measurements from these different methods, resulting in a more accurate and precise definition of the property boundaries. This is especially critical in complex or litigious situations where minor errors can have significant legal and financial consequences.

Q 21. What are the advantages and disadvantages of different adjustment methods?

Various adjustment methods exist, each with its advantages and disadvantages. The optimal choice depends on the specific application, data characteristics, and desired accuracy. Let’s compare two commonly used methods:

- Least Squares Adjustment:

- Advantages: Statistically rigorous, provides a best-fit solution, produces measures of uncertainty, widely used and well-understood.

- Disadvantages: Computationally intensive, may be sensitive to outliers, assumes a linear model (which may not always be accurate).

- Robust Estimation Techniques (e.g., RANSAC, Least Median of Squares):

- Advantages: Less sensitive to outliers, can handle non-linear models.

- Disadvantages: Can be less efficient, may not always provide the most accurate solution, may require more tuning of parameters.

For instance, least squares is ideal for highly accurate geodetic networks with minimal outliers. Robust methods are suitable where outliers are likely, for example in image matching where some false correspondences might occur. The selection of method is often a careful balance between computational efficiency, robustness, and the specific characteristics of the data at hand.

Q 22. Explain how to perform a simple linear regression adjustment.

Simple linear regression adjustment is a statistical method used to find the best-fitting straight line through a set of data points. This line, representing the relationship between a dependent variable and an independent variable, allows us to predict the dependent variable’s value given a value for the independent variable. It’s like drawing the ‘line of best fit’ on a scatter plot.

The process involves finding the slope (m) and y-intercept (b) of the line that minimizes the sum of the squared differences between the observed values and the values predicted by the line (this is called minimizing the sum of squared residuals). This is done using the method of least squares.

Steps:

- Calculate the means: Find the average of your x-values (μx) and y-values (μy).

- Calculate the slope (m): m = ∑[(xi – μx)(yi – μy)] / ∑[(xi – μx)2], where xi and yi are individual data points.

- Calculate the y-intercept (b): b = μy – mμx.

- Form the equation: The equation of the line is now y = mx + b. This equation allows you to predict y for any given x.

Example: Let’s say we’re adjusting survey measurements. We have a series of measured distances (x) and corresponding GPS distances (y). By performing a linear regression, we can find the relationship between the two, allowing us to adjust all future survey measurements using the equation of the line.

Q 23. How do you handle missing data in adjustment computations?

Handling missing data in adjustment computations is crucial for maintaining the integrity and accuracy of the results. Ignoring missing data can lead to biased and unreliable conclusions. Several methods exist, each with its strengths and weaknesses:

- Deletion: The simplest approach is to remove any observation containing missing data. This is only suitable if the missing data is small and random; otherwise, it can introduce bias.

- Imputation: This involves replacing missing values with estimated values. Methods include mean imputation (replacing with the mean of the available data), regression imputation (predicting the missing value based on other variables), and more sophisticated techniques like k-nearest neighbors or multiple imputation.

- Model-based approaches: Some statistical models are specifically designed to handle missing data, such as maximum likelihood estimation in the context of a mixed-effects model. This is often preferred for complex datasets with intricate patterns of missing data.

The best method depends on the nature of the missing data (missing completely at random (MCAR), missing at random (MAR), or missing not at random (MNAR)), the amount of missing data, and the characteristics of the dataset. It’s often advisable to explore multiple methods and compare the results.

For instance, in a geodetic network adjustment, if a few coordinates are missing due to instrument malfunction, imputation might be appropriate. However, if a significant portion of data is missing due to systematic errors, a more detailed investigation and potentially a different data collection strategy would be needed.

Q 24. Describe the role of software in performing adjustment computations.

Software plays a vital role in performing adjustment computations, especially for large and complex datasets. Manual calculations are impractical and prone to errors. Software packages provide efficient tools for:

- Data input and management: Easily input large amounts of data, manage different data formats, and detect inconsistencies.

- Computation of adjustments: Perform various adjustment techniques like least squares, weighted least squares, and robust methods. These techniques handle inconsistencies and provide more reliable results.

- Error analysis and diagnostics: Identify and quantify errors, assess the reliability of the results, and provide visual representations for quick understanding.

- Result visualization: Display results in various formats (tables, graphs, maps) for effective interpretation and communication.

- Automation and reproducibility: Automate repetitive tasks and ensure reproducibility of analyses, crucial for quality control and reporting.

Without software, processing even moderately sized adjustment computations would be extremely time-consuming and error-prone. Imagine manually calculating the adjustment for a large geodetic network—it’s simply not feasible.

Q 25. What are some common software packages used for adjustment computations?

Many software packages are available for adjustment computations, catering to various needs and levels of expertise. Some popular choices include:

- MATLAB: A powerful programming environment with extensive toolboxes for statistical analysis and numerical computation.

- R: An open-source statistical programming language with a rich ecosystem of packages for adjustment computations and data visualization.

- Python (with libraries like NumPy, SciPy, pandas): A versatile programming language with libraries capable of handling large datasets and complex calculations, offering flexibility and customizability.

- Specialized geodetic software packages: Several software packages are designed specifically for geodetic and surveying applications, such as GeoOffice, Leica GeoMoS, and others. These often have user-friendly interfaces and built-in functions for common adjustment techniques.

The choice of software depends on factors like the complexity of the computation, the size of the dataset, the user’s programming skills, and the specific requirements of the project.

Q 26. Explain the importance of quality control in adjustment computations.

Quality control (QC) in adjustment computations is paramount for ensuring the reliability and validity of the results. Errors in data acquisition, processing, or computation can significantly affect the outcome. QC involves a series of checks and procedures aimed at identifying and minimizing errors.

Key aspects of QC include:

- Data validation: Checking for outliers, inconsistencies, and missing data. This might involve visual inspection of data, statistical tests, and data consistency checks.

- Redundancy analysis: Using redundant measurements to improve accuracy and detect errors. The more redundant measurements, the better the error detection capabilities.

- Residual analysis: Examining the residuals (differences between observed and adjusted values) to identify potential systematic errors or outliers.

- Statistical tests: Applying statistical tests to assess the goodness of fit and identify potential problems in the adjustment model.

- Independent verification: Having another person or team independently review the computations and results.

Consider a bridge construction project: inaccurate adjustment computations could compromise the structural integrity of the bridge, leading to disastrous consequences. Therefore, rigorous QC procedures are essential in any application where the results have significant implications.

Q 27. How do you document your adjustment computations?

Proper documentation of adjustment computations is crucial for reproducibility, transparency, and traceability. A well-documented adjustment computation allows others to understand the methods, data, and results, and to verify the work.

Essential elements of documentation include:

- Project description: A clear explanation of the project’s objectives, the data used, and the methods applied.

- Data description: A detailed description of the data, including sources, formats, and any pre-processing steps.

- Methodology: A clear description of the adjustment method used, including the model, assumptions, and any constraints.

- Software and parameters: Specification of the software used, including version numbers, and any relevant parameters.

- Results: Presentation of the results in a clear and concise manner, including tables, graphs, and maps.

- Error analysis: Assessment of the accuracy and precision of the results, including error statistics and error ellipses.

- Quality control checks: A detailed description of the QC steps performed, and the results of these checks.

Effective documentation can involve using version control systems, maintaining detailed logs of all actions, and employing standardized reporting formats. This ensures not only the quality of the work but also the possibility to easily retrace every step in the process.

Q 28. Describe a situation where you had to troubleshoot an error in an adjustment computation.

During a large-scale geodetic network adjustment for a highway construction project, I encountered an unexpectedly large standard deviation in the adjusted coordinates of several points. Initially, I suspected gross errors in the measurements. However, a thorough review of the residuals revealed no clear outliers.

I then investigated the covariance matrix and discovered a high degree of correlation between certain observations. This indicated a potential problem with the model’s assumptions—specifically, the assumption of independent errors. Further analysis revealed that a small number of baseline measurements were highly correlated due to the observation geometry. The baselines were measured along a single straight section of the highway. This collinearity introduced instability in the adjustment and inflated the standard deviations.

To solve this, I re-evaluated the observation strategy and added more strategically located measurements to reduce the correlation. This enhanced the strength of the adjustment by improving the geometric configuration of the network. After re-performing the adjustment with the improved data, the standard deviations dropped to an acceptable level, and the results became reliable. This situation highlighted the importance of proper observation planning and a deep understanding of the statistical model’s assumptions.

Key Topics to Learn for Adjustment Computations Interview

- Least Squares Adjustment: Understand the fundamental principles and applications of the least squares method in solving adjustment problems. Explore its role in minimizing errors and achieving optimal solutions.

- Error Propagation and Analysis: Master techniques for propagating errors through computations and analyzing the precision and reliability of adjusted values. Practice identifying and mitigating sources of error.

- Geodetic Network Adjustment: Learn to apply adjustment computations to geodetic networks, understanding concepts like coordinate transformations, datum transformations, and the impact of different network geometries.

- Constraint Equations and Conditions: Develop a strong understanding of how to incorporate constraints and conditions into adjustment models, ensuring realistic and physically feasible solutions.

- Software Applications: Familiarize yourself with common software packages used for adjustment computations. Understand their functionalities and limitations.

- Practical Applications: Explore real-world applications of Adjustment Computations in surveying, GIS, mapping, and other relevant fields. Consider case studies to solidify your understanding.

- Matrix Algebra Fundamentals: Reinforce your knowledge of matrix operations, as they form the backbone of many adjustment computation techniques.

Next Steps

Mastering Adjustment Computations opens doors to exciting career opportunities in fields demanding high precision and accuracy. A strong foundation in this area significantly enhances your employability and potential for career advancement. To maximize your job prospects, creating an ATS-friendly resume is crucial. ResumeGemini can help you build a compelling and effective resume that highlights your skills and experience in Adjustment Computations. We provide examples of resumes tailored to this specific field to guide you in crafting a professional document that showcases your expertise. Invest time in building a strong resume – it’s your first impression on potential employers.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO