Every successful interview starts with knowing what to expect. In this blog, we’ll take you through the top Deep Diving and Wreck Exploration interview questions, breaking them down with expert tips to help you deliver impactful answers. Step into your next interview fully prepared and ready to succeed.

Questions Asked in Deep Diving and Wreck Exploration Interview

Q 1. Describe your experience with different types of diving equipment (e.g., regulators, BCD, drysuits).

My experience with diving equipment spans decades and encompasses a wide range of gear. Regulators, the lifeline between diver and air supply, are crucial. I’ve worked with both diaphragm and piston regulators, understanding their mechanics and maintenance requirements. A faulty regulator can be life-threatening, so regular servicing and familiarity with different makes and models is paramount. Buoyancy Compensators (BCDs) are equally critical for controlling buoyancy. I’m proficient with both jacket-style and back-inflation BCDs, adjusting buoyancy profiles based on depth, dive profile, and the type of diving activity. Dry suits are essential for deep diving and wreck exploration in colder waters. I have extensive experience with various dry suit materials, including neoprene and trilaminate, and understand the importance of proper undergarment layering for thermal protection and maintaining dexterity. I’m also familiar with different valve types and sealing techniques to prevent leaks and maintain optimal suit inflation. I’ve also handled various other equipment like dive computers, underwater lights, and specialized tools for wreck penetration.

Q 2. Explain the principles of decompression and how it relates to deep diving.

Decompression is the process of allowing dissolved inert gases, primarily nitrogen, to gradually leave the body’s tissues after a dive. At depth, the pressure increases, forcing more nitrogen into our bloodstream and tissues. Ascending too quickly allows these gases to form bubbles, leading to decompression sickness. The principles involve understanding the relationship between depth, time, and the partial pressure of nitrogen. Dive tables and dive computers calculate decompression stops based on these factors, allowing sufficient time for nitrogen to be eliminated safely. In deep diving, where the partial pressure of nitrogen is significantly higher, decompression stops become longer and more critical to prevent decompression sickness. The longer the exposure to high pressure and the deeper the dive, the more rigorous the decompression plan must be. Failure to follow these procedures can have severe and even fatal consequences.

Q 3. What are the different types of decompression sickness, and how are they treated?

Decompression sickness manifests in various ways. Type I, also known as mild DCS, involves symptoms such as joint pain (the bends), fatigue, and skin rashes. Type II DCS is more severe, potentially affecting the central nervous system, causing paralysis, seizures, or even loss of consciousness. Treatment for Type I DCS often involves recompression therapy in a hyperbaric chamber, forcing the dissolved gases back into solution and allowing them to be eliminated safely. Type II DCS requires immediate and aggressive treatment in a hyperbaric chamber, often involving multiple recompression sessions. Oxygen is frequently administered during treatment. Early recognition of symptoms is key to successful treatment. Prevention is always better than cure; proper dive planning and adhering to decompression procedures drastically reduces the risk.

Q 4. Describe your experience with navigation underwater, including the use of compasses and other tools.

Underwater navigation requires a combination of skills and tools. A compass is fundamental, allowing orientation and maintaining a bearing. I’m proficient in using a compass, accounting for magnetic declination and other environmental factors that can affect its accuracy. I often use natural navigation techniques, identifying landmarks, remembering the route, and using underwater terrain features to navigate and avoid getting lost. On wreck dives, visual cues, such as the shape of the wreck, the direction of current flow, and artificial markers like marker lines, are essential for safe navigation. Other tools I use include dive slates for recording information, and underwater cameras and video equipment which can serve as a visual log of the dive, supporting subsequent navigation attempts in the same location. Planning the route beforehand, using charts and sonar data, is crucial for any complex dive, particularly when exploring unfamiliar wreck sites.

Q 5. How do you manage emergencies during a dive, such as equipment failure or diver distress?

Emergency management during a dive is paramount. My training emphasizes preparedness and proactive risk mitigation. If a diver experiences equipment failure, such as a regulator free-flow, the immediate response involves switching to an alternate air source. Proper buddy system training enables immediate assistance and support for distressed divers. I’m proficient in performing emergency ascents, carefully controlling buoyancy and rate of ascent to minimize the risk of decompression sickness. We are trained in various rescue techniques, including assisting an unconscious diver to the surface and performing emergency first aid and oxygen administration. Effective communication through hand signals is crucial in underwater emergencies. Regular drills and training sessions enhance our readiness to handle a wide range of potential scenarios. Regular review of emergency procedures is critical to ensure competency.

Q 6. Explain the procedures for conducting a pre-dive safety check.

A thorough pre-dive safety check is non-negotiable. It’s a systematic process, typically following a checklist. First, I inspect my own equipment: regulators (checking for free flow, air supply), BCD (inflation and deflation mechanisms), dry suit (seals, inflation), dive computer (battery, settings). I then check my buddy’s equipment, ensuring it is functioning correctly. We verify that our dive plan is appropriate for the conditions, including weather, visibility, and depth. The dive site is assessed for potential hazards, such as strong currents, sharp debris, or potential entanglement points on wrecks. Our communication systems and emergency procedures are reviewed and tested. This rigorous pre-dive check not only ensures the safety of the dive but also enhances our teamwork and coordination.

Q 7. What are the legal and regulatory requirements for deep diving and wreck exploration in your region?

(Note: This answer will vary depending on the specific region. The following is a general example and should be replaced with information specific to a real location.) In many regions, deep diving and wreck exploration are subject to strict regulations. These typically include licensing requirements for divers, certification levels relevant to the depth and complexity of the dives, and permits or permissions for accessing specific dive sites, particularly wrecks. Environmental protection laws usually restrict or prohibit disturbing artifacts or harming the marine environment. There might also be regulations concerning the use and carrying of decompression equipment, and reporting procedures to follow in the event of an incident. Specific local regulations must be consulted and adhered to prior to any deep dive or wreck exploration. Ignoring these regulations can result in legal penalties, including fines and suspension of diving licenses.

Q 8. Describe your experience with underwater photography or videography.

Underwater photography and videography are crucial for documenting wreck dives, both for scientific purposes and to share the experience. My experience spans over 15 years, encompassing various techniques and equipment. I’m proficient in using both still cameras and video cameras in underwater housings, including DSLR and mirrorless systems. I understand the challenges of lighting, buoyancy control, and composition in the underwater environment. For example, during a recent exploration of the SS President Coolidge wreck in Vanuatu, I employed strobe lighting to capture the vibrant colors of the coral growth on the ship’s hull and the intricate details of its internal structures, using a wide-angle lens for the overall shots and a macro lens for smaller details. I also utilize specialized underwater lighting techniques, like using multiple strobes to avoid harsh shadows and achieve even illumination. Post-processing is also a key component; I’m adept at using software like Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop to enhance image quality and correct for color casts caused by water absorption.

Q 9. Explain your understanding of underwater communication methods.

Underwater communication is paramount for safety and efficiency. While speech is significantly impaired underwater, we rely on a combination of methods. Most commonly, we use hand signals, which are standardized and universally understood among divers. These signals cover everything from emergency situations (like running out of air) to indicating direction or confirming actions. For longer distances or situations where hand signals are difficult, we use underwater slates, which are waterproof writing boards. These are especially useful for communicating findings or observations about the wreck. More technologically advanced divers utilize underwater communication systems, either through acoustic signals (similar to underwater sonar) or through specialized diver-to-diver communication devices that transmit sound via water, but these are often expensive and may be prone to interference. In a situation where there’s a diver suffering from decompression sickness, clear and rapid communication through pre-agreed hand signals to surface support is vital, quickly informing the team to begin a safe ascent and treatment.

Q 10. What are the common hazards associated with wreck diving?

Wreck diving presents unique hazards beyond those of typical open-water diving. These include:

- Structural instability: Wreck decay can lead to collapses, entrapment, or the release of debris.

- Entanglement: Wires, fishing nets, and other debris pose a significant risk of entanglement and panic.

- Reduced visibility: Sediment stirred up by divers or currents can significantly reduce visibility, leading to disorientation.

- Confined spaces: Penetration diving inside a wreck introduces the dangers of restricted movement, air depletion, and limited escape routes.

- Environmental hazards: Sharp edges, rusty metal, and hazardous materials can cause injuries.

- Marine life: While generally fascinating, some marine life inhabiting wrecks can pose a danger if provoked.

Proper training, careful planning, and adherence to safety procedures are vital to mitigate these risks. For instance, thorough wreck assessment before entering is non-negotiable.

Q 11. How do you assess the structural integrity of a wreck before entering?

Assessing a wreck’s structural integrity before entry involves a multi-faceted approach. Firstly, I review any available historical records and surveys of the wreck to understand its known structural weaknesses. Then, from a safe distance, visual inspection from above and around the wreck is undertaken, looking for signs of collapse, significant rusting, or areas of deterioration. I will use a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) or a diver to assess hard-to-reach areas. I carefully check for any signs of recent collapse or instability, such as debris fields nearby or sections of the wreck that look loose or weakened. Finally, the planned penetration points must be inspected for possible structural compromise and alternate entry and exit points should be identified and planned for.

Q 12. Describe your experience with penetration diving.

Penetration diving is a specialized aspect of wreck diving that involves entering and navigating the interior spaces of a sunken vessel. My extensive experience includes over 100 penetration dives on a variety of wrecks. This requires advanced training, specialized equipment (like reels for line management and redundant air supplies), and strict adherence to safety protocols. Each penetration dive necessitates thorough planning, including establishing clear entry and exit points, deploying a guideline system for navigation and emergency egress, and utilizing multiple sources of lighting. I’ve had many memorable dives, including an exploration of the Umbria wreck in the Red Sea, where navigating the ship’s internal compartments, full of wartime cargo, was a challenging yet rewarding experience. The use of reliable dive lights is critical, as visibility inside wrecks can be minimal and even the use of multiple torches can be insufficient to illuminate the entire area. Safety is always the primary concern, and this is reinforced through meticulous planning and adherence to training.

Q 13. What are the different types of dive profiles, and when would you use each one?

Dive profiles describe the pattern of depth and time during a dive. Several types exist, selected based on the dive’s objectives and complexity:

- Square profile: A dive that spends a significant period at a constant depth (e.g., wreck exploration).

- Triangular profile: A slow descent, long bottom time at a shallower depth, and a slow ascent (suited for introductory dives).

- Multi-level profile: Involves multiple depths and bottom times, useful for wreck penetration or exploring a complex environment.

- Deco profile: Includes decompression stops during the ascent to safely off-gas inert gases from the body’s tissues, required for deeper or longer dives.

Choosing the right profile is critical for safety. For a deep wreck penetration, a deco profile is mandatory to account for nitrogen build-up in the body at depth. For a simple shallow reef dive, a triangular profile might be sufficient.

Q 14. How do you plan and execute a complex dive operation?

Planning and executing a complex dive operation, such as a large wreck exploration, is a multi-stage process requiring meticulous attention to detail. First, we conduct comprehensive pre-dive planning, including site surveys (possibly with ROVs), determining dive profiles and contingency plans, gathering meteorological data, and assembling the appropriate equipment and personnel. Thorough risk assessments are vital, identifying and mitigating potential hazards. The detailed dive plan is then reviewed and approved by all dive team members, especially with respect to any risks associated with the wreck and the dive parameters. During the dive, continuous monitoring of divers’ conditions (air supply, depth, and time) and the wreck’s integrity is essential. Communication within the team remains paramount, using the various methods discussed earlier. Post-dive, the team conducts a thorough debriefing session, evaluating the success of the operation, noting any unexpected issues, and identifying areas for improvement in future operations.

Q 15. Explain your experience with the use of specialized diving equipment (e.g., rebreathers, sidemount systems).

My experience with specialized diving equipment is extensive, encompassing both rebreathers and sidemount systems. Rebreathers, which recycle a diver’s exhaled breath, offer significantly extended bottom times and reduced gas consumption, crucial for deep and technical wreck exploration. I’m proficient with various rebreather models, from the KISS (Keep It Simple Stupid) style to more advanced closed-circuit units, understanding their operational intricacies, maintenance protocols, and emergency procedures. I’ve used them extensively in complex cave and wreck penetrations, where their silent operation and extended duration are paramount.

Sidemount configurations, where cylinders are mounted along the diver’s sides, provide superior trim and maneuverability, particularly within the confines of a wreck. This setup allows for efficient gas management and easier access to multiple gas sources. I’ve incorporated sidemount techniques into many of my wreck dives, finding it advantageous in challenging environments where precise buoyancy control and efficient movement are essential.

For instance, during a recent exploration of the SS President Coolidge wreck in Vanuatu, the sidemount system allowed me to navigate the complex corridors and compartments with ease, while the rebreather ensured I had the bottom time required to thoroughly document the site.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Describe your experience with underwater search and recovery techniques.

Underwater search and recovery techniques are integral to my work. This involves a methodical approach, combining advanced navigation skills, precise buoyancy control, and the use of specialized equipment like underwater metal detectors, sonar, and powerful underwater lights. The process often begins with a thorough pre-dive planning phase, encompassing the study of historical records, site surveys (if possible), and the creation of detailed dive plans.

Search patterns vary depending on the environment and target. A common technique is a systematic grid search, ensuring complete coverage of the search area. For wreck exploration, this involves using visual cues, sonar data, and even underwater robots in challenging situations. Once the target is located, recovery requires careful lifting techniques and the appropriate equipment to safely bring the object to the surface, all while maintaining safe diving practices and mitigating potential hazards.

For example, during a search for lost artifacts from a historical shipwreck, we employed a combination of magnetic anomaly detection and a grid search pattern. This resulted in locating several significant artifacts buried in the seabed which were then carefully recovered using a lifting bag.

Q 17. How do you manage gas consumption during a dive?

Gas management is critical to diver safety, especially in deep or extended dives. Careful pre-dive planning is crucial, calculating gas requirements based on depth, bottom time, ascent rate, and safety stops. The use of dive computers that track gas consumption in real-time is essential. These computers constantly monitor the diver’s depth, time, and gas pressure allowing for precise adjustments to the dive plan.

Techniques like managing ascent rate to ensure sufficient gas supply for decompression stops, making use of gas switching (moving to a stage cylinder at a specific depth), and incorporating contingency plans for gas emergencies are all part of my repertoire. During the dive itself, I constantly monitor my gas pressure gauges and maintain awareness of my remaining air supply. I also regularly practice gas sharing drills with my dive partners to ensure we are prepared for emergency situations.

Imagine a deep penetration wreck dive – effective gas management would involve carrying multiple gas cylinders with different gas mixes, ensuring sufficient decompression gas and contingency supplies. This avoids the potentially fatal situation of running out of air at depth.

Q 18. What are the signs and symptoms of nitrogen narcosis and oxygen toxicity?

Nitrogen narcosis and oxygen toxicity are two significant hazards in diving, especially at depth. Nitrogen narcosis, also known as ‘rapture of the deep,’ is caused by increased nitrogen partial pressure at depth, affecting cognitive function. Symptoms range from slight impairment in judgment to severe disorientation, euphoria, and hallucinations, very similar to alcohol intoxication.

Oxygen toxicity, on the other hand, arises from high partial pressure of oxygen. It can manifest in different ways, from mild irritation of the respiratory system (coughing, burning sensation in the lungs) to severe central nervous system effects like seizures and even death. Symptoms are more likely at higher partial pressures of oxygen, and longer exposure time further increases the risk.

Recognizing these symptoms is vital for diver safety. If a diver exhibits unusual behavior or physiological changes during a dive, an immediate ascent is necessary. Pre-dive planning to limit depth and bottom time can reduce the risk of both narcosis and oxygen toxicity.

Q 19. What is your experience with using different types of dive computers?

I’m experienced with a wide array of dive computers, from basic recreational models to advanced technical dive computers with multiple gas capabilities. My experience includes both analog and digital gauges, understanding their functionalities and limitations. The choice of dive computer depends heavily on the complexity of the dive. For recreational dives, a simpler model may suffice; however, technical dives require advanced features to manage multiple gases, decompression profiles, and other critical parameters.

I’m proficient in using computers that calculate decompression profiles using different algorithms (e.g., Bühlmann, ZHL-16B), allowing for personalized decompression strategies. I also routinely check the computer’s settings, battery life, and sensor calibration to ensure accurate data and reliable performance. A malfunctioning dive computer can compromise the safety of a dive; hence, redundant systems are often employed, and thorough pre-dive checks are essential.

For instance, during a complex cave system penetration, I rely on a dive computer with multiple gas switching capabilities and a robust decompression algorithm, backed up by additional depth and time monitoring gauges.

Q 20. Explain the principles of buoyancy control.

Buoyancy control is fundamental to safe and efficient diving. It involves managing the diver’s overall buoyancy to maintain neutral buoyancy – a state where neither ascent nor descent requires effort. This is achieved by precisely controlling the amount of air in the buoyancy compensator (BCD) and adjusting the weight system to maintain the desired position in the water column.

Proper buoyancy control minimizes the use of fins for vertical movement and enhances the diver’s overall efficiency and stability. It allows for precise maneuvering, essential for navigating wrecks, caves, and other complex environments. Skills like proper weighting (not being too heavy or too light), and mastering the technique of subtle buoyancy adjustments are extremely important.

Effective buoyancy control minimizes damage to the environment (preventing the accidental disturbance of the seabed or coral) and makes diving safer and more enjoyable. I practice this skill continuously during each dive, constantly refining my technique to become even more precise.

Q 21. Describe your understanding of underwater currents and how they affect diving operations.

Understanding underwater currents is crucial for safe diving operations. Currents can vary significantly in strength and direction, influenced by factors like tides, wind, and the surrounding topography. Strong currents can make diving extremely challenging, potentially leading to exhaustion, disorientation, and even loss of control.

Pre-dive planning often involves studying local current patterns and predicting their strength and direction based on tidal information and weather forecasts. During the dive, I constantly monitor the current’s strength and direction. Navigation strategies may need to be adjusted to account for the current’s effect. For example, I’ll use a safety stop location that is sheltered from a strong current, or I might even choose to delay a dive if conditions become too hazardous.

My experience includes navigating strong currents during wreck penetrations, requiring precise buoyancy control and efficient finning techniques to maintain position and manage ascent and descent. Using a planned approach and understanding the current is vital to preventing unsafe situations and to maximize the efficiency and safety of the dive.

Q 22. What safety procedures do you follow during night dives?

Night diving presents unique challenges, demanding heightened safety protocols. Visibility is drastically reduced, increasing the risk of collisions and disorientation. Therefore, a robust system of communication and redundancy is crucial.

- Redundant Lighting: We always carry at least three dive lights – a primary light, a backup, and a smaller light for close-range inspection. Regular checks throughout the dive ensure they’re functioning properly. Imagine diving in a deep wreck; a single light failure could be catastrophic.

- Enhanced Communication: We use dive lights to signal each other, employing agreed-upon hand signals alongside verbal communication when possible. This becomes vital in low visibility. A simple flashing light pattern could signal an emergency.

- Buddy System: The buddy system is paramount, with constant physical contact or close proximity maintained. This allows for immediate assistance if one diver experiences a problem. Think of it like a safety net – one diver is always watching out for the other.

- Pre-Dive Briefing: A thorough pre-dive briefing covering the dive plan, potential hazards, and emergency procedures is essential. This briefing also includes contingency plans for equipment failure and unexpected scenarios.

- Slow and Steady: Night dives are conducted at a slower pace, allowing more time to react to potential hazards and reducing the risk of accidents. We always remain aware of the ambient surroundings and other divers.

Q 23. Describe your experience with working as part of a dive team.

Working as part of a dive team is fundamental to safe and efficient wreck exploration. It’s not just about individual skills; it’s about seamless coordination and trust. My experience highlights the importance of:

- Roles and Responsibilities: Within a team, roles are clearly defined. Some focus on navigation, others on photography or documentation, while others manage safety and equipment. This division of labour is crucial for productivity.

- Communication: Clear, concise, and unambiguous communication is paramount. We utilize a mix of hand signals, slates (underwater writing pads), and sometimes even underwater communication devices depending on the complexity of the dive and depth. A simple miscommunication underwater could have severe consequences.

- Shared Decision-Making: Difficult decisions are made collaboratively. For instance, if visibility drops significantly, the team might decide to abort the dive based on a collective assessment of risk.

- Debriefing: Post-dive debriefings are crucial. We discuss what worked well, what could have been improved, and any lessons learned from the dive. This is how experience is shared and safety protocols are constantly refined.

For example, during a recent survey of a submerged aircraft, one team member focused on using a sonar system to create a map, while another documented the wreck’s condition, and I navigated us through the wreck’s debris field.

Q 24. How do you deal with difficult or stressful situations during a dive?

Difficult situations underwater require calm, decisive action and adherence to established protocols. My approach involves:

- Assessment: First, assess the situation objectively: What is the problem? What are the immediate risks? What resources are available?

- Communication: Communicate the issue clearly to my dive buddy and the team. This involves using established hand signals and communication methods to ensure understanding.

- Problem-Solving: Apply problem-solving techniques. This might involve deploying emergency equipment, adjusting the dive plan, or initiating an ascent if necessary. Every situation is different, but the underlying principle remains: prioritize safety.

- Controlled Ascent: If a significant problem arises (e.g., equipment malfunction, disorientation), a controlled and planned ascent to the surface is prioritized. Speed and panic are counterproductive. We always follow established ascent rates to avoid decompression sickness.

In one instance, a team member’s primary regulator failed at depth. Through quick action, calm communication, and the use of a backup regulator, the dive was safely aborted.

Q 25. What is your experience with underwater surveying techniques?

Underwater surveying techniques are essential for wreck exploration, providing detailed information about the site’s condition and history. My experience includes various methods:

- Sonar: Using side-scan sonar and multibeam echo sounders to create detailed maps of the seabed and identify wreck locations. This is like using an underwater radar to see the unseen.

- Photogrammetry: Capturing overlapping photographs of the wreck to create 3D models using specialized software. This allows us to examine the wreck in detail, even after the dive.

- Video Surveys: Recording high-definition video footage using underwater cameras, which is then used for documentation, analysis, and research purposes.

- Manual Measurements: Using measuring tapes and other tools to record dimensions and locations of key features of the wreck. This is often used for documenting the physical condition and decay rate of the wreck

- Data Logging: Precisely recording all data, including compass bearings, depths, and GPS coordinates, to accurately position and document findings.

Combining these methods provides a comprehensive understanding of the wreck site.

Q 26. How do you maintain and service diving equipment?

Proper maintenance and servicing are crucial for the safety and longevity of diving equipment. My routine involves:

- Regular Inspections: Before every dive, I meticulously inspect all equipment, checking for wear, tear, and damage. This is a non-negotiable safety check.

- Cleaning: After each dive, equipment is thoroughly rinsed with fresh water to remove salt and debris. Failing to do so leads to corrosion and equipment failure.

- Component Checks: Regularly checking and servicing individual components (regulators, BCD, etc.) according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

- Professional Servicing: Undergoing regular professional servicing by qualified technicians to ensure proper functioning and safety. This includes annual checks and overhauls.

- Storage: Proper storage of equipment in a dry, clean environment, away from direct sunlight and extreme temperatures, ensures its lifespan. Improper storage accelerates deterioration.

Neglecting maintenance puts lives at risk. It is a costly mistake to cut corners on proper equipment maintenance.

Q 27. Describe your experience with different types of underwater environments.

My experience encompasses a wide variety of underwater environments, each presenting unique challenges and requiring specialized techniques.

- Reefs: Diving on coral reefs requires careful navigation to avoid damaging the delicate ecosystem. Buoyancy control and maintaining a safe distance from the reef are crucial.

- Wreck Diving: Wreck diving demands advanced skills in navigation, penetration, and decompression procedures. Understanding the potential hazards within a wreck (entrapment, structural instability) is essential.

- Cave Diving: Cave diving is highly specialized and only undertaken by trained professionals. It requires mastery of line management, gas planning, and advanced navigation skills. This is some of the most dangerous forms of diving.

- Open Ocean: Open ocean dives often involve strong currents and reduced visibility. Precise buoyancy control and planning are essential for safety.

- Deep Diving: Deep dives necessitate meticulous planning, specialized equipment (e.g., technical diving gear), and extensive training to avoid decompression sickness.

Adaptability and the ability to adjust to different conditions are key to success and safety in all environments.

Q 28. What is your understanding of the environmental impact of diving activities?

The environmental impact of diving activities, if not managed responsibly, can be significant. Understanding this impact is critical.

- Coral Damage: Divers can inadvertently damage coral reefs through physical contact, improper buoyancy control, or by disturbing sediments. Careful fin placement and maintaining good buoyancy are crucial to avoid this.

- Marine Life Disturbance: Divers should minimize disturbance to marine life by avoiding touching or chasing animals. Maintaining a respectful distance allows marine life to behave naturally.

- Pollution: Divers should avoid discarding anything in the water, including sunscreen which is damaging to coral. Responsible disposal of waste is crucial for preserving the underwater environment.

- Anchor Damage: The use of anchors can damage seagrass beds and coral reefs. Using mooring lines is a preferred alternative.

- Sustainable Practices: Educating divers about responsible dive practices, promoting conservation, and supporting organizations dedicated to marine protection are vital.

Minimizing our impact is crucial for protecting this fragile ecosystem for future generations.

Key Topics to Learn for Deep Diving and Wreck Exploration Interview

- Dive Planning and Safety Procedures: Understanding decompression models, gas management strategies, emergency procedures, and risk assessment methodologies crucial for safe and successful dives.

- Wreck Penetration Techniques: Mastering navigation within confined spaces, utilizing specialized equipment (e.g., reels, lights, SMBs), and practicing safe entry/exit procedures.

- Underwater Surveying and Documentation: Proficiency in using underwater survey equipment (e.g., sonar, cameras, 3D scanners), data logging, and preparing detailed dive reports.

- Environmental Awareness and Conservation: Knowledge of marine ecosystems, responsible diving practices, and the impact of wreck exploration on the environment. Understanding relevant regulations and permits.

- Equipment Maintenance and Repair: Hands-on experience with scuba gear, underwater lighting, and other specialized equipment, including troubleshooting and basic repair techniques.

- Dive Physiology and Decompression Sickness: In-depth understanding of the physiological effects of pressure changes on the human body, recognizing symptoms of decompression sickness, and implementing appropriate treatment protocols.

- Legal and Ethical Considerations: Awareness of relevant laws and regulations governing wreck exploration, ethical considerations regarding historical artifacts, and responsible interaction with authorities.

- Teamwork and Communication: Demonstrating strong communication skills, collaborative work in a team environment, and the ability to effectively communicate underwater using signals and equipment.

- Problem-Solving and Decision-Making Under Pressure: Highlighting experience in handling unexpected situations, making quick and informed decisions in challenging environments, and adapting to changing conditions.

Next Steps

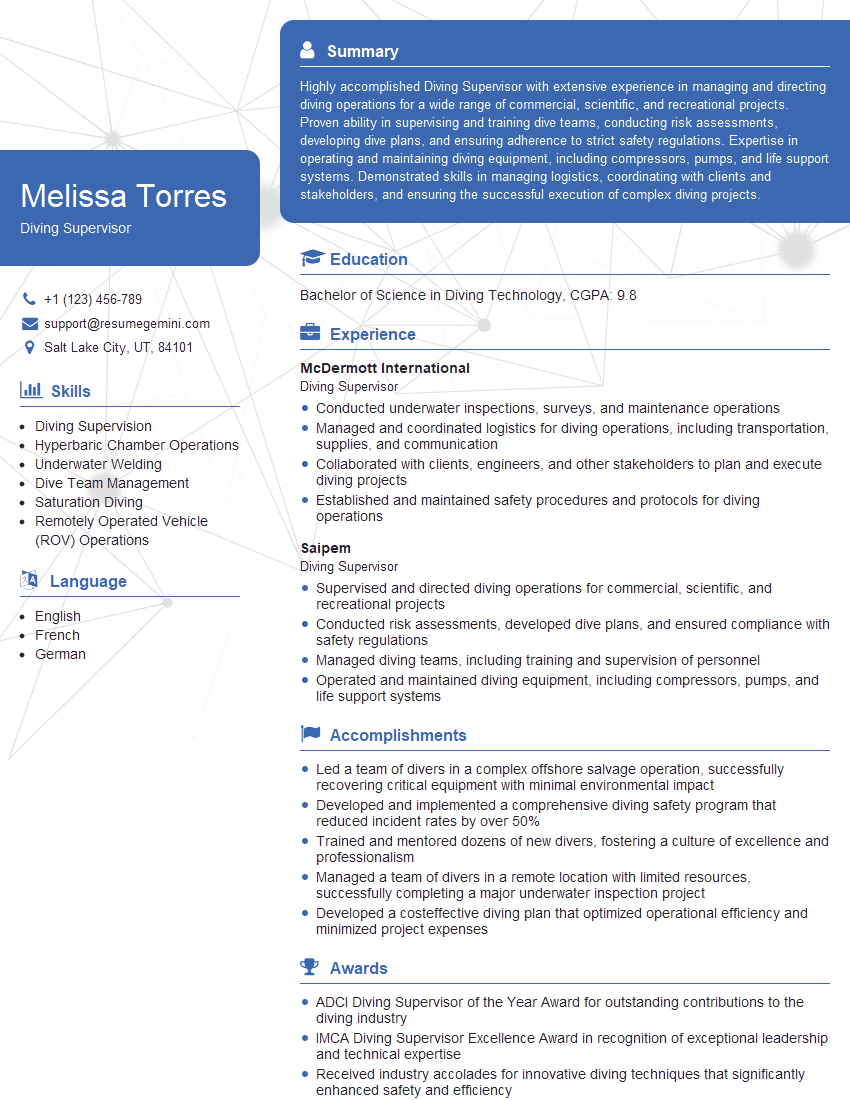

Mastering Deep Diving and Wreck Exploration opens doors to exciting career opportunities in research, commercial diving, underwater archaeology, and more. To stand out from the competition, create a compelling and ATS-friendly resume that showcases your skills and experience. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource to help you build a professional resume that highlights your unique qualifications. We offer examples of resumes tailored to Deep Diving and Wreck Exploration to guide you in crafting your perfect application. Take the next step in your career journey today.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO