Unlock your full potential by mastering the most common Diving interview questions. This blog offers a deep dive into the critical topics, ensuring you’re not only prepared to answer but to excel. With these insights, you’ll approach your interview with clarity and confidence.

Questions Asked in Diving Interview

Q 1. Describe your experience with different types of diving equipment.

My experience with diving equipment spans a wide range, from basic open-circuit scuba gear to more specialized equipment like rebreathers and technical diving configurations. I’m proficient with various regulator types, including diaphragm and piston designs, understanding their strengths and limitations in different diving environments. I’ve extensively used different buoyancy compensator devices (BCDs), from jacket-style to back-inflate models, recognizing how their design impacts trim and maneuverability. Furthermore, my experience includes using various types of dive computers, dry suits, underwater communication systems, and specialized lighting equipment for deep dives and cave explorations. I’ve worked with both aluminum and steel scuba tanks, understanding the differences in buoyancy and capacity. I’m also familiar with different types of underwater cameras and housings for capturing underwater imagery.

- Regulators: I’ve used both low-pressure and high-pressure regulators, appreciating the benefits of each design for different diving scenarios and depths.

- BCDs: I understand the importance of proper BC sizing and inflation techniques for maintaining optimal buoyancy and control.

- Dry Suits: I’m trained in the proper donning, doffing, and maintenance of dry suits, crucial for cold-water diving.

Q 2. Explain the principles of buoyancy control.

Buoyancy control is the art of managing your position in the water column using the interplay of your buoyancy compensator (BCD), weight system, and breath control. It’s fundamental to safe and efficient diving. The principle is based on Archimedes’ principle: an object submerged in a fluid experiences an upward buoyant force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced. To achieve neutral buoyancy (hovering effortlessly), the diver must adjust their volume to match the surrounding water’s pressure, thereby balancing the buoyant force and their weight. This is done by adjusting the air in their BCD, adding or removing weights, and controlling their lung volume. Proper buoyancy control allows the diver to move smoothly and effortlessly through the water, conserving energy and minimizing disturbance to the marine environment. Imagine trying to balance a scale: your weight is one side, and the buoyant force is the other. You adjust the air in your BCD like adjusting weights on the scale to achieve perfect balance.

Poor buoyancy control can lead to excessive finning, inefficient gas consumption, and potentially dangerous situations like uncontrolled ascents or descents. Practicing buoyancy control in a controlled environment such as a pool is crucial before venturing into open water.

Q 3. What are the signs and symptoms of decompression sickness?

Decompression sickness (DCS), also known as the bends, occurs when dissolved inert gases, primarily nitrogen, form bubbles in the body’s tissues and bloodstream during ascent from a dive. The rate at which these gases come out of solution depends on pressure changes and the duration of the dive. Symptoms can vary widely, ranging from mild to severe and can appear immediately after the dive or hours later. Mild symptoms might include fatigue, joint pain (the ‘bends’), itching, or skin rash. More serious symptoms can manifest as neurological problems, such as dizziness, paralysis, loss of consciousness, or difficulty breathing. In severe cases, DCS can be fatal. The time between the dive and symptom onset is very important diagnostically.

It’s crucial to seek immediate medical attention if any symptoms are suspected. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is often required to treat decompression sickness.

Q 4. How do you manage an out-of-air emergency?

An out-of-air emergency is a critical situation requiring immediate action. The first and most important step is to remain calm. Panic will exacerbate the situation. Signal your buddy using your alternate air source and ascend together slowly and controlled, making sure to maintain proper buoyancy and following established ascent procedures. If a buddy is unavailable, calmly initiate your emergency ascent procedure, conserving what little air is left to manage buoyancy on the ascent. Once surfaced, call for help immediately using a whistle, signaling device, or radio if available.

Prevention is key. Always dive with a buddy, check each other’s air supply regularly, and plan the dive so that you always have enough air to reach the surface with a comfortable margin of safety. Regularly practicing emergency ascent procedures in training is vital for preparedness.

Q 5. What are the procedures for conducting a pre-dive safety check?

A pre-dive safety check, also known as a buddy check, is a crucial step before every dive. It’s a systematic process to ensure all diving equipment is functioning correctly and the diver is properly prepared. The check typically follows a standard procedure, often using an acronym like BWRAF (BCD, weights, releases, air, final check). Each element is examined thoroughly. For the BCD, I check the inflator and deflator mechanisms, making sure there are no leaks or damage. For weights, I ensure that they are securely attached and properly weighted for the dive plan. I verify that all releases— including the quick-release buckles on the BC and tank—are functioning smoothly and safely. For air, I check the pressure gauge reading on my tank and verify there’s sufficient air for the planned dive, including reserve. I then perform a final check, ensuring everything is in order. This includes the mask, fins, snorkel, and any other personal equipment.

A thorough buddy check ensures both the divers and their gear are ready for a safe and enjoyable dive. It helps prevent equipment malfunctions and minimizes the risk of accidents.

Q 6. Describe your experience with different types of dive computers.

My experience encompasses various dive computer models, from basic air-integrated units to advanced nitrox and trimix-capable computers. I’m familiar with different manufacturers and their unique features, understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each. I’ve utilized computers with features such as air integration, depth tracking, ascent rate monitoring, dive time tracking, and decompression algorithms. I can interpret the data provided by these devices to ensure safe and efficient dives, making informed decisions regarding gas management and ascent profiles. For example, I’ve worked with computers using both Bühlmann and ZHL-16B decompression models, understanding the implications of using different algorithms for different dive profiles.

The choice of dive computer depends on the type of diving being performed – recreational, technical, or cave diving – each requiring different features and capabilities.

Q 7. Explain the importance of proper gas management during a dive.

Proper gas management during a dive is essential for safety and enjoyment. It involves carefully monitoring air consumption, planning for contingencies, and making informed decisions based on air pressure, depth, and dive time. This includes calculating the amount of air needed for the dive, including a safety margin. Regularly checking your air supply and your buddy’s air supply is also crucial. Knowing your personal consumption rate and accounting for potential factors like current or cold water that might impact air usage helps to manage air appropriately. Insufficient gas planning can lead to an out-of-air emergency, a potentially dangerous situation. Efficient gas management also involves proper buoyancy control to minimize unnecessary movement and energy expenditure, thereby extending air supply.

Experienced divers understand their personal air consumption and the factors that influence it, allowing them to anticipate and respond appropriately to unexpected situations.

Q 8. How do you calculate bottom time and decompression stops?

Calculating bottom time and decompression stops is crucial for diver safety and involves understanding several factors. Bottom time is the total time spent underwater, excluding ascent and descent. Decompression stops are mandatory pauses during ascent to allow the body to release dissolved nitrogen safely, preventing decompression sickness (DCS), also known as ‘the bends’.

Calculating Bottom Time: This is relatively straightforward. You simply record the time you begin your descent and the time you begin your ascent. The difference is your bottom time.

Calculating Decompression Stops: This is more complex and typically relies on dive tables or dive computers. These tools consider several variables:

- Depth: The deeper you dive, the more nitrogen your body absorbs, requiring longer decompression stops.

- Bottom Time: Longer bottom times lead to increased nitrogen saturation, necessitating more decompression stops.

- Dive Profile: Repeated dives or rapid ascents increase risk, influencing decompression stop requirements.

- Altitude: Diving at higher altitudes requires more conservative decompression plans.

Dive Tables: Traditional dive tables use a grid system correlating depth and bottom time to determine decompression obligations. They offer various levels of conservatism based on the experience and training of the diver. Using a table requires careful attention to detail and accurate timekeeping.

Dive Computers: Modern dive computers continuously monitor depth, time, and ascent rate, calculating the necessary decompression stops automatically. They provide real-time feedback, reducing the margin for human error. However, it’s crucial to understand the limitations and functionalities of your specific dive computer and always plan for contingencies.

Example: Let’s say a diver spends 30 minutes at a depth of 30 meters (98 feet). A dive table or computer would indicate whether decompression stops are needed based on that information, perhaps indicating a 3-minute stop at 6 meters (20 feet) on the ascent.

Q 9. What are the common causes of dive accidents?

Dive accidents, sadly, are not uncommon. They stem from a multitude of factors, often involving a combination of human error and environmental challenges. Some common causes include:

- Decompression Sickness (DCS): This is a serious condition arising from ascending too quickly, resulting in nitrogen bubbles forming in the bloodstream. Symptoms can range from mild joint pain to paralysis or even death.

- Nitrogen Narcosis: Also known as ‘rapture of the deep,’ this is a condition caused by increased nitrogen pressure at depth affecting the central nervous system, leading to impaired judgment and decision-making.

- Oxygen Toxicity: Breathing high partial pressures of oxygen at depth can damage the lungs and central nervous system. This is primarily a concern in technical diving.

- Air Supply Issues: Running out of air is a significant hazard. Proper planning, monitoring air consumption, and having sufficient reserves are crucial.

- Equipment Malfunctions: Faulty equipment can lead to various problems, from regulator failure to buoyancy control issues. Regular equipment maintenance and pre-dive checks are essential.

- Poor Planning & Execution: Inadequate planning, neglecting to account for environmental conditions (currents, tides, weather), or failing to follow established safety procedures significantly increases the risk of accidents.

- Improper Buoyancy Control: Collisions with the bottom or other divers, and difficulties controlling ascents and descents are often due to problems with buoyancy.

- Entanglement: Getting entangled in fishing lines, nets, or wreck debris can cause panic and create a hazardous situation.

Preventing dive accidents relies heavily on proper training, careful planning, adherence to safety guidelines, and continuous self-assessment and skill enhancement.

Q 10. Describe your experience with different dive environments (e.g., ocean, cave, wreck).

My diving experience spans a variety of environments, each presenting unique challenges and rewards:

- Ocean Diving: I have extensive experience in open ocean dives, ranging from calm coastal waters to more challenging environments with strong currents and varying visibility. I’ve participated in dives exploring diverse marine life, coral reefs, and underwater geological formations. Adapting to varying conditions and currents is crucial in this environment.

- Cave Diving: Cave diving requires specialized training and equipment. The confined nature of caves necessitates meticulous planning, exceptional buoyancy control, and an understanding of navigation techniques specific to subterranean environments. Line laying and following are key skills. I’ve completed several cave dives, always prioritizing safety and working with a qualified team.

- Wreck Diving: Wreck diving offers a unique perspective into maritime history. I have experience navigating and exploring various sunken vessels, from small boats to larger ships. The potential for entanglement, structural instability, and limited visibility requires careful planning and a thorough understanding of the dive site.

In each environment, maintaining situational awareness, responsible diving practices, and respect for the limitations of my skills and equipment are paramount.

Q 11. What is your experience with emergency ascent procedures?

Emergency ascent procedures are critical to handle situations requiring a rapid return to the surface. The specific procedure depends on the emergency but generally involves:

- Controlled Emergency Ascent: This is the preferred method if possible. Involves a slow, controlled ascent, making decompression stops as necessary, to avoid DCS. If an out-of-air situation arises, one would share air with a buddy or initiate an emergency ascent.

- Emergency Buoyant Ascent: This involves rapidly ascending to the surface, using a buoyancy compensator or discarding weight to reach the surface quickly. This carries a significantly increased risk of DCS and should only be used as a last resort if other options are unavailable, for example if the diver is running out of air and a buddy is unable to assist.

- Post-Ascent Procedures: After any emergency ascent, immediate first aid, oxygen administration if available, and contacting emergency medical services are critical. Symptoms of DCS should be closely monitored.

Training in emergency ascent procedures is vital for all divers. Practice and thorough understanding of the procedures and associated risks are essential in responding effectively to unexpected events.

Q 12. How do you handle equipment malfunctions during a dive?

Equipment malfunctions can occur at any time. My approach involves a structured process:

- Assessment: Quickly assess the nature and severity of the malfunction. Is it a minor inconvenience or a major safety issue?

- Problem Solving: If possible, attempt to resolve the issue using available resources. For example, a minor regulator freeflow might be solved by clearing the regulator. A major problem would necessitate an alternative.

- Safety First: If the malfunction compromises safety, initiate an appropriate emergency procedure immediately. This might involve signaling for help, a controlled ascent, or the use of backup equipment.

- Buddy Support: Effective buddy teamwork is crucial. My buddy and I are trained to assist each other in case of equipment failure. We communicate clearly during a dive and are constantly aware of each other’s status.

- Post-Dive Review: After the dive, it’s essential to thoroughly inspect the malfunctioning equipment to determine the cause and prevent future issues. Note any problems to take action with the equipment.

Regular equipment maintenance and pre-dive checks are the best ways to mitigate the risk of equipment failure.

Q 13. Explain the importance of dive planning and briefing.

Dive planning and briefing are fundamental to safe and enjoyable dives. They help mitigate risks and ensure a cohesive team effort.

- Dive Planning: Involves selecting an appropriate dive site based on experience, weather conditions, and dive profile requirements. It includes checking depth, currents, visibility, and potential hazards. Gas planning is crucial, which determines how much gas you’ll consume considering how long you are planning to be at the site.

- Dive Briefing: A pre-dive briefing occurs before entering the water. It serves to review the dive plan, discuss potential hazards, and confirm equipment functionality and emergency procedures. It’s a collaborative process involving all divers. Briefings ensure every diver is aware of the plan and knows what to do in the event of problems.

Example: Before a wreck dive, the briefing would include discussing the location, depth, potential currents, the wreck’s condition (structural integrity), entry and exit points, and procedures for navigating the site and exiting in a calm and safe manner. The briefing would also cover emergency procedures, contingency plans, and communication signals.

Thorough dive planning and briefing fosters a culture of safety and teamwork, significantly reducing the likelihood of accidents and enhancing the overall quality of the dive.

Q 14. Describe your experience with rescue techniques.

Rescue techniques are essential skills for divers. My training encompasses a range of procedures:

- Recognizing Distress: Quickly identifying a diver in distress, whether through visual cues (unusual behavior, struggles), or verbal communication.

- Approaching Safely: Approaching a distressed diver without creating further panic or entanglement.

- Assisting with Equipment: Providing air if needed, assisting with buoyancy control, or helping to untangle equipment.

- Emergency Ascends: Assisting a diver with an emergency buoyant ascent, offering support and control. This is done carefully to help the ascent and ensure the safety of both divers.

- Towing: Towing an incapacitated diver to the surface.

- Surface Support: Providing assistance at the surface, including helping a diver exit the water and initiating first aid if necessary.

Rescue techniques are best learned through dedicated training courses, practiced regularly, and refined during experience.

Q 15. What are the limits of your diving certification?

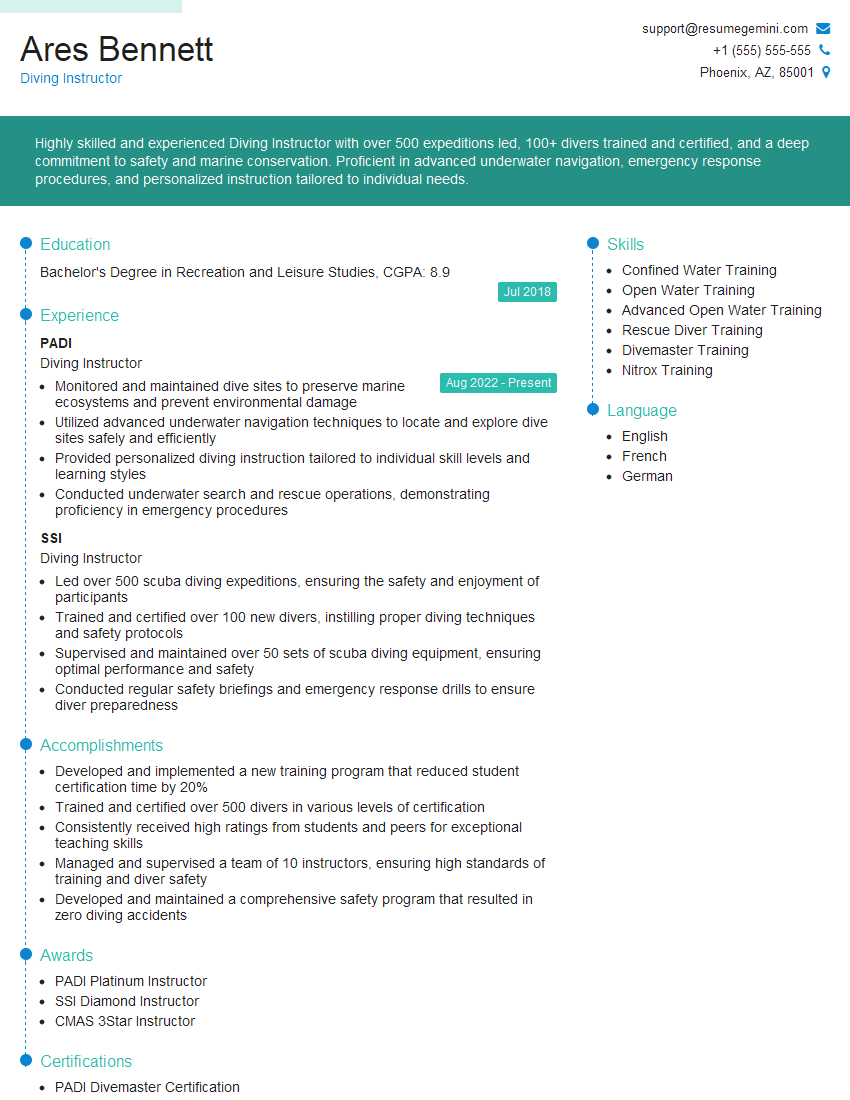

My diving certification is as a PADI Divemaster. This means I’m qualified to guide certified divers, assist instructors, and supervise dive operations within the limits of my training. Crucially, this doesn’t grant me the ability to independently teach diving courses or conduct dives beyond the parameters set by my training agency. For example, I’m proficient in open water dives to a maximum depth of 40 meters (130 feet), but I cannot independently lead technical dives involving decompression stops or rebreathers. I am limited to recreational diving practices.

My certification limits are clearly defined in my certification card and I adhere strictly to those limits. This means being acutely aware of my own limits and those of the divers I guide, and always prioritizing safety.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. What is your experience with underwater communication?

Underwater communication is paramount for safety and efficiency. My experience encompasses a range of techniques, starting with the basics of hand signals, which are essential for conveying critical information like air supply levels, ascent signals, or pointing out marine life. I’m proficient in using a slate and pencil for more detailed communication, especially in situations where hand signals might not be sufficient. During dives with multiple divers, I’ve learned how to utilize a dive computer with a built-in communication system for direct diver to diver communication at moderate depths. I’ve even had experience working with divers who use specialized underwater communication devices that utilize sound waves. This is important in situations with poor visibility. The key is adapting communication methods to suit the conditions and to always maintain effective communication to ensure the safety and understanding of everyone involved in the dive.

Q 17. Explain the importance of maintaining proper situational awareness during a dive.

Maintaining proper situational awareness is fundamental to safe diving. It’s about constantly monitoring your environment – your air supply, depth, location, the behavior of your dive buddy, and the surrounding marine life. Imagine you’re navigating a busy city street; you’d constantly look both ways, be aware of the traffic, and anticipate potential hazards. Underwater is no different, except the hazards might be strong currents, sudden changes in visibility, or encounters with potentially dangerous marine life. Losing situational awareness can lead to accidents. In practice, this means regularly checking your gauges, staying within designated dive areas, maintaining visual contact with your dive buddy, and being alert to any changes in the environment. For example, if the current suddenly picks up, we must react instantly; a sudden change in water clarity can mean that we need to amend our dive plan, and an unexpected marine animal might signal an early ascent. In short, a diver who maintains situational awareness is a safe diver.

Q 18. Describe your experience with navigation underwater.

My experience with underwater navigation involves using a compass, dive maps, and natural features. I’ve navigated using a compass and maintaining a bearing while also understanding how to utilize natural landmarks like reefs or rock formations to help maintain our planned course. I’ve conducted several dives where we used a dive computer with GPS to track our position, especially in murky waters or large dive areas. For example, we might use a compass to maintain a bearing to a distant landmark or reef and then use the topography of the seabed to ensure that we are following our planned dive path. I understand the limitations of these methods and know how to adjust plans based on changes in conditions. Poor visibility requires even greater attention to detail and reliance on the compass, potentially incorporating a safety line to maintain position relative to our starting point. Accurate underwater navigation is crucial to prevent disorientation and ensure a timely and safe return to the surface.

Q 19. How do you assess dive site conditions before entering the water?

Before entering the water, I thoroughly assess dive site conditions by checking several factors: first and foremost, I’ll check the weather conditions; next, I’ll check the depth, current conditions, and visibility. I look at the surface conditions – wind speed and wave height to check for suitability of the dive plan, as well as any noticeable weather changes in the surroundings. I will assess potential hazards such as strong currents, potential marine wildlife, depth, and visibility. I will check the latest dive reports from other divers at the location to check for unforeseen issues and consider whether our planned dive path is safe given any current conditions and visibility. I also consult local knowledge or dive guides if available. If I deem any aspect unsafe, I will adjust or postpone the dive, prioritizing safety above all else.

Q 20. Explain the different types of dive profiles.

Dive profiles describe the depth and time spent at each depth during a dive. There are various types, but the most common are:

- Recreational dives: These usually involve a relatively straightforward descent to a chosen depth, a period of bottom time, and a direct ascent, adhering to no-decompression limits.

- Decompression dives: These involve deeper dives and longer bottom times, requiring planned decompression stops during ascent to allow the body to safely release dissolved nitrogen. These dives require specialized training and equipment.

- Multi-level dives: Involve several distinct periods spent at different depths, usually to explore various features of the dive site. This can increase the overall risk and should be planned carefully.

- Penetrative dives: Involve entering enclosed environments like caves or wrecks. These dives demand significant planning, specialized equipment, and increased risk assessment considerations.

Understanding the dive profile is crucial for safe and efficient planning, particularly in regards to managing decompression and avoiding risks such as decompression sickness (the bends).

Q 21. How do you conduct a post-dive safety debrief?

A post-dive safety debrief is a critical step in ensuring future safety. It involves a discussion among the dive team to review the dive, identify any potential issues, and learn from the experience. I typically follow these steps: First, we discuss any issues encountered during the dive such as unusual currents or wildlife encounters. Second, we evaluate the effectiveness of our communication and teamwork. Did we adhere to the dive plan? Were there any communication breakdowns? Finally, we assess the effectiveness of our safety procedures; were they adequate or could any of them have been improved? The debrief helps identify areas for improvement, share insights, and enhance team cohesion and safety. For example, if we encountered strong currents, the debrief could lead to a revised dive plan for future dives in similar conditions. By continually learning and adapting from each dive, we enhance safety and minimize risk. The focus is on continuous improvement for future dives.

Q 22. What are the regulations governing your type of diving?

Diving regulations vary significantly depending on location, the type of diving (e.g., recreational, commercial, scientific), and the specific activity. Generally, they cover safety standards, equipment requirements, diver training certifications, and environmental protection. For example, recreational diving is often governed by national or regional agencies that set minimum training standards and require divers to carry specific equipment, such as buoyancy compensators (BCDs) and dive computers. Commercial diving, on the other hand, is usually subject to much stricter regulations due to the higher risk involved. These often include mandatory medical examinations, detailed dive plans, and specific safety procedures for working in potentially hazardous environments. Furthermore, environmental regulations dictate where and how divers can operate to protect sensitive ecosystems. These might include restrictions on touching or disturbing marine life, limitations on the use of certain equipment near coral reefs, or designated no-dive zones. Understanding and adhering to these regulations is paramount for safe and responsible diving.

Q 23. What is your experience with dive boat safety procedures?

My experience with dive boat safety procedures is extensive. I’ve participated in numerous dives from various vessels, ranging from small inflatable boats to larger, purpose-built dive boats. I’m familiar with all aspects of pre-dive checks, including the emergency equipment, such as oxygen, first-aid kits, and communication devices. I understand the importance of briefing procedures, including risk assessments, dive site characteristics, and emergency plans. I’m well-versed in the safe loading and unloading of divers and equipment, the use of appropriate safety gear, such as life jackets and harnesses, and the implementation of appropriate procedures during emergencies, such as a diver running into trouble. For instance, during a dive off the coast of Cozumel, our boat experienced a sudden engine failure. The captain, following established protocol, calmly anchored the boat, deployed emergency equipment, and communicated with other vessels. The dive master, meanwhile, meticulously guided the divers back to the boat safely. It highlights the importance of teamwork and planning when dealing with unforeseen circumstances on a dive boat. I also know the importance of maintaining a logbook for each trip, detailing weather conditions, dive profiles, and any noteworthy incidents.

Q 24. Describe your experience with maintaining dive equipment.

Maintaining dive equipment is crucial for safety and reliability. My experience includes regular inspection and cleaning of all my gear, from my BCD and regulator to my wetsuit and dive computer. I perform thorough pre-dive checks before every dive, and more extensive servicing every six months or after intensive use. I also keep detailed records of maintenance, including dates and any repairs or replacements. For example, I carefully check the integrity of my O-rings, ensuring they are lubricated and not damaged. I also test my buoyancy control to ensure optimal performance. Failing to maintain equipment can lead to malfunctions which can result in serious incidents underwater. Regular servicing is just as important as pre-dive checks, extending the life of the equipment, ensuring it remains safe to use, and enhancing reliability.

Q 25. Explain the principles of decompression theory.

Decompression theory centers around the concept of dissolved gases, primarily nitrogen, in the body’s tissues at depth. As a diver descends, the surrounding pressure increases, allowing more nitrogen to dissolve into the blood and tissues. A slow ascent allows the body to gradually release this nitrogen through exhalation, preventing the formation of bubbles (decompression sickness or ‘the bends’). The rate at which nitrogen dissolves and desaturates is dependent on various factors, including depth, dive duration, and the individual’s physiology. Dive computers utilize decompression models and algorithms to calculate safe ascent rates and decompression stops, taking these factors into account. Failure to follow the recommended decompression procedures can result in decompression sickness, characterized by joint pain, neurological symptoms, or even paralysis in severe cases. Understanding decompression theory is crucial for making informed decisions regarding dive planning and execution.

Q 26. Describe your experience working with a dive team.

I have extensive experience working with dive teams in various settings, from recreational dive trips to more complex technical dives. Effective teamwork is paramount for safety and efficiency underwater. This involves clear communication, both above and below the surface, mutual respect, and a shared understanding of the dive plan. I’m comfortable with various roles within a dive team, including dive master, buddy diver, and team leader. A memorable example involves rescuing a diver with an equipment malfunction during a night dive. Teamwork and swift responses were critical in bringing the diver to the surface safely and unharmed. Effective teamwork relies on regular training, clear communication, mutual respect, and shared responsibility for ensuring the safety of each team member.

Q 27. How do you handle conflict within a dive team?

Conflict within a dive team can compromise safety, so addressing it promptly and professionally is essential. My approach involves open and honest communication. I strive to understand each person’s perspective, focusing on finding a mutually acceptable solution that prioritizes safety. If a conflict involves critical safety concerns or involves a serious breach of diving protocols, it needs to be escalated to the relevant authorities immediately. I believe in a preventative approach, emphasizing pre-dive briefings to clarify roles, responsibilities, and expectations. Maintaining a respectful and collaborative atmosphere is key to preventing many potential conflicts.

Q 28. What are your personal limitations as a diver?

Recognizing personal limitations is crucial in diving. My limitations include a mild case of color blindness that impacts my ability to distinguish certain colors at depth. This means I rely more on other visual cues and always dive with a buddy who can assist in this aspect. Additionally, my fitness levels are consistently monitored. I understand that exceeding my physical limits could put myself and my team at risk. I maintain a thorough understanding of my personal limitations to avoid situations where these limitations might compromise my safety or the safety of my dive buddies.

Key Topics to Learn for Your Diving Interview

- Dive Planning & Safety Procedures: Understanding risk assessment, emergency procedures, and pre-dive checks is crucial. Consider how you’d apply these in various dive scenarios.

- Dive Physics & Physiology: Mastering concepts like buoyancy control, decompression theory, and the effects of pressure on the human body will demonstrate a strong theoretical foundation. Be prepared to explain how these impact dive planning and execution.

- Dive Equipment & Maintenance: Familiarize yourself with different types of diving equipment, their functions, and routine maintenance procedures. Highlight your experience with troubleshooting and equipment repair.

- Navigation & Underwater Communication: Demonstrate your skills in underwater navigation techniques and various communication methods used during dives. Discuss practical applications in challenging underwater environments.

- Environmental Awareness & Conservation: Understanding marine ecosystems, responsible diving practices, and the impact of diving on the environment is vital. Be ready to discuss your commitment to sustainability and conservation.

- Dive Tables & Decompression Calculations: Show your understanding of dive tables and decompression calculations. Be able to explain how to interpret them and adapt them to different dive profiles.

- Rescue & First Aid Techniques: Highlight your knowledge of emergency response procedures, including administering first aid underwater and on the surface. Explain your experience with various rescue scenarios.

Next Steps

Mastering the skills and knowledge required for diving opens doors to exciting and rewarding career opportunities in this dynamic field. To maximize your chances of landing your dream job, creating a compelling and ATS-friendly resume is paramount. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource that can help you build a professional resume that showcases your expertise and experience effectively. We provide examples of resumes tailored to the diving industry to help guide you in crafting the perfect application. Take the next step toward your dream diving career today!

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO