Interviews are more than just a Q&A session—they’re a chance to prove your worth. This blog dives into essential Emergency Response and Dive Accident Management interview questions and expert tips to help you align your answers with what hiring managers are looking for. Start preparing to shine!

Questions Asked in Emergency Response and Dive Accident Management Interview

Q 1. Describe the stages of decompression sickness.

Decompression sickness, also known as ‘the bends,’ occurs when dissolved gases, primarily nitrogen, come out of solution in the body’s tissues and fluids as a diver ascends too quickly. This formation of bubbles causes a range of symptoms depending on the severity and location of the bubbles.

- Stage 1: Mild Decompression Sickness: This stage involves symptoms like fatigue, joint pain (the bends), itching, and skin rash (cutis marmorata). It’s crucial to remember that even mild symptoms warrant immediate medical attention as they can progress rapidly. For example, a diver might complain of achy joints after a dive, initially dismissing it, only to experience worsening symptoms later.

- Stage 2: Moderate Decompression Sickness: This presents with more severe symptoms, such as significant joint pain, neurological symptoms like numbness or tingling (paresthesia), and breathing difficulties. A diver might struggle to walk or experience impaired coordination. Imagine a diver suddenly losing the ability to use their arms or legs.

- Stage 3: Severe Decompression Sickness: This is a life-threatening condition. Symptoms can include paralysis, loss of consciousness, seizures, respiratory failure, and even cardiac arrest. This stage often requires immediate recompression therapy to prevent permanent disability or death. Think of a diver who completely loses motor function and requires immediate advanced medical care.

It’s vital to emphasize that the progression of symptoms can be rapid and unpredictable. Early recognition and treatment are crucial for a positive outcome.

Q 2. Explain the different types of diving emergencies.

Diving emergencies encompass a broad spectrum of life-threatening situations. They can be broadly categorized as:

- Decompression Sickness (DCS): As discussed previously, this arises from gas bubble formation due to rapid ascent.

- Air Embolism: This occurs when air enters the bloodstream, often due to a ruptured lung during ascent. This is a critical emergency, potentially leading to stroke, cardiac arrest, or death. Imagine a diver holding their breath during a rapid ascent, causing a lung rupture and air entering the bloodstream.

- Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE): A more severe form of air embolism, involving air bubbles in the arteries, often affecting the brain or heart.

- Nitrogen Narcosis: This is a neurological impairment at depth, similar to alcohol intoxication, affecting judgment and decision-making. This can lead to risky behavior and accidents underwater.

- Oxygen Toxicity: Exposure to high partial pressures of oxygen can damage the lungs and central nervous system. This is more common in technical diving.

- Equipment Failure: This covers malfunctioning equipment like regulators, buoyancy compensators, or dive computers, leading to loss of buoyancy, air supply, or navigational issues.

- Drowning: This can result from equipment failure, panic, or other underwater incidents.

- Trauma: Injuries sustained underwater, such as collisions with marine life or objects.

Effective emergency response requires a thorough understanding of all these potential scenarios to initiate appropriate and timely interventions.

Q 3. What are the key components of a dive accident response plan?

A robust dive accident response plan is essential for managing diving emergencies. Key components include:

- Pre-dive planning: This involves selecting appropriate dive sites, considering environmental conditions, and ensuring proper equipment maintenance and functionality. Knowing the dive profile and having a comprehensive dive plan is vital.

- Buddy system: Diving with a buddy ensures mutual support and immediate assistance in case of an emergency.

- Emergency communication protocols: Establishing clear procedures for contacting emergency services and relaying critical information to rescue teams. This often involves pre-determined signal systems and communication devices.

- Emergency equipment: Having readily available emergency oxygen, first-aid kits, and appropriate rescue equipment.

- Trained personnel: Having personnel trained in first aid, CPR, and dive rescue techniques.

- Access to recompression chamber: Knowing the location and contact information of the nearest recompression chamber is crucial in cases of DCS or AGE.

- Post-accident procedures: Establishing procedures for documenting the incident, conducting post-dive briefings, and handling paperwork.

Regular drills and training are critical to ensure the effectiveness of the plan in real-world situations. A well-rehearsed plan drastically improves the chances of successful outcomes.

Q 4. How do you assess a diver’s condition upon surfacing?

Assessing a diver’s condition upon surfacing requires a systematic approach. The ABCDE method is a helpful framework:

- A – Airway: Check for airway obstruction and ensure the diver can breathe easily.

- B – Breathing: Assess the rate, depth, and quality of breathing. Look for signs of respiratory distress.

- C – Circulation: Check for a pulse and signs of bleeding. Assess skin color and temperature.

- D – Disability: Evaluate neurological status, checking for consciousness, orientation, and motor function. Look for symptoms of DCS or AGE, such as paralysis, numbness, or disorientation.

- E – Exposure: Protect the diver from environmental hazards and hypothermia. Keep them warm and dry.

Note any symptoms reported by the diver, and immediately initiate appropriate first aid and emergency medical services if necessary. Time is critical in diving emergencies; rapid and accurate assessment is paramount.

Q 5. What are the limitations of using a recompression chamber?

Recompression chambers are invaluable in treating DCS and AGE, but they have limitations:

- Accessibility: Recompression chambers are not always readily available, especially in remote dive locations. Travel time to reach a chamber can delay treatment, negatively impacting the outcome.

- Cost: Treatment in a recompression chamber is expensive.

- Not a cure-all: While highly effective, recompression therapy cannot guarantee a full recovery in all cases. The severity of the condition, the time elapsed before treatment, and individual patient factors influence the outcome.

- Potential risks: Although rare, there are potential risks associated with recompression therapy, including oxygen toxicity and barotrauma.

- Treatment complexity: The recompression process itself is highly specialized and requires trained personnel to operate.

Despite these limitations, access to a recompression chamber significantly improves the chances of survival and minimizes long-term complications in severe cases of decompression sickness.

Q 6. Outline the steps involved in performing an underwater search and recovery operation.

Underwater search and recovery operations demand meticulous planning and execution. Steps generally include:

- Planning & Briefing: Thorough planning based on information about the missing diver, including last known location, dive profile, and equipment. This includes a safety briefing for all personnel involved.

- Search Pattern Selection: Choosing an appropriate search pattern, such as a grid search or a spiral search, based on the circumstances. This is crucial for efficient coverage of the search area.

- Environmental Assessment: Assessing underwater conditions like visibility, currents, and depth to determine the best approach and equipment.

- Search Techniques: Utilizing various techniques including visual search, sonar, or remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) depending on the circumstances and the nature of the search area.

- Recovery Techniques: Selecting the best approach for retrieving the object or diver, accounting for factors like depth, current, and potential hazards.

- Debriefing: A post-operation debriefing to evaluate the effectiveness of the operation and identify areas for improvement in future missions.

Safety is paramount throughout the entire operation. The environment can be unpredictable and dangerous, requiring careful planning and execution.

Q 7. Explain the proper procedures for handling a diver experiencing an air embolism.

Handling a diver experiencing an air embolism is a critical emergency requiring immediate action. The primary focus is to provide life support and transport the diver to definitive care as quickly as possible:

- 100% Oxygen Administration: Immediately administer 100% oxygen via a mask or other appropriate device. Oxygen is crucial to help the body compensate and reduce the damage caused by the air embolism.

- High-Flow Oxygen: If available, use a high-flow oxygen system to maximize oxygen delivery. This is more efficient than standard oxygen masks.

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR): If the diver is unconscious and not breathing, immediately start CPR while simultaneously providing oxygen. This is a life-saving intervention.

- Rapid Transport: Arrange for immediate transport to a medical facility with appropriate capabilities. The faster the transport, the better the chance of a positive outcome.

- Recompression: Recompression therapy is usually necessary. This should be arranged if a recompression chamber is readily accessible.

- Ongoing Monitoring: Throughout the process, continuously monitor the diver’s vital signs (pulse, breathing, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation) and provide appropriate supportive care.

Air embolism is a serious condition with a high mortality rate, so swift and effective intervention is crucial. Remember, every minute counts in this life-threatening situation.

Q 8. Describe the different types of dive equipment and their functions.

Dive equipment is broadly categorized into several essential components, each playing a vital role in diver safety and mission success. Think of it like a finely tuned orchestra – each instrument is critical for a harmonious performance, and in diving, that means a safe and successful dive.

- Buoyancy Compensator (BCD): This is your personal flotation device, allowing you to control your buoyancy underwater by adding or removing air. Imagine it as the volume control on a set of speakers – adjusting the air adjusts your depth. Failure of a BCD can lead to rapid ascent or descent, so regular maintenance and inspection are crucial.

- Dive Regulator: This transforms the high-pressure air in your tank into breathable air at a safe pressure. It’s like a sophisticated pressure reducer, ensuring you can breathe comfortably at depth. A malfunctioning regulator can lead to a catastrophic breathing emergency.

- Dive Computer: This advanced device monitors your dive profile (depth, time, ascent rate), alerting you to potential hazards like decompression sickness. Think of it as your flight recorder, continuously tracking vital data to protect your safety.

- Scuba Tank (Cylinder): This compressed air source provides the diver’s breathable air supply. The pressure gauge on the tank tells you the amount of air remaining. Always plan your dives with adequate air reserves and dive with a buddy who can share their supply in an emergency.

- Mask and Snorkel: Essential for clear underwater vision and surface breathing. A cracked mask can severely impair visibility and lead to panic, while a failing snorkel can create difficulties in the event of an emergency.

- Fins and Weight Belt: Fins propel the diver underwater, while weights compensate for the buoyancy of the wetsuit and equipment, allowing neutral buoyancy. Improper weighting can lead to uncontrolled ascent or descent.

- Dive Suit (Wetsuit, Drysuit): These provide thermal protection, preventing hypothermia in cold water. A compromised suit can lead to rapid heat loss and serious consequences.

Regular maintenance and inspection of all dive equipment are paramount to ensuring a safe dive. Treating each piece as a crucial element of your life support system is essential.

Q 9. How do you communicate effectively in an underwater environment during an emergency?

Underwater communication during emergencies requires a multi-faceted approach, combining visual signals, physical contact, and, where available, underwater communication devices. Think of it as a layered approach to ensure the message gets through.

- Visual Signals: Hand signals, agreed upon beforehand, are crucial. A simple thumbs-up can mean ‘okay,’ while a clenched fist to the throat signals a breathing problem. Divers should practice these signals regularly, ensuring they understand each other’s signals in a high-stress environment.

- Physical Contact: In low-visibility situations or when communication devices fail, physical contact provides a means of guidance and support. A gentle tap on the shoulder can draw attention, while a firm grip might indicate a need for assistance.

- Underwater Communication Devices: Dive slates (waterproof writing pads) and underwater communication systems (using acoustic signals) offer additional communication options, especially for complex situations or larger dive teams. However, always prioritize a pre-agreed visual signaling system.

- Surface Communication: Maintaining visual contact with the dive support boat is critical. Surface markers and signals are crucial in indicating the diver’s position and any potential problems.

Effective communication hinges on pre-dive planning and thorough training. A well-rehearsed plan and clear communication protocols significantly increase the likelihood of a successful emergency response.

Q 10. What are the legal and ethical considerations in dive accident management?

Dive accident management involves significant legal and ethical responsibilities. It’s about not only saving lives but also adhering to regulations and demonstrating responsible conduct. Negligence can have severe repercussions.

- Legal Considerations: Depending on location, regulations dictate the level of training, equipment, and safety protocols required for diving operations. Failing to adhere to these rules can lead to hefty fines or even criminal charges, especially in the case of diver fatalities or injuries resulting from negligence. Operators and dive leaders need to be thoroughly familiar with local and national diving regulations.

- Ethical Considerations: Ethics play a pivotal role. Divers and dive operators have a responsibility to prioritize the safety of all participants. This includes proper pre-dive planning, risk assessment, monitoring of divers, and swift, effective response to any incidents. Making informed decisions, ensuring diver competency and respecting the marine environment, are all core ethical considerations. A strong sense of responsibility and a commitment to safe practice are crucial.

- Duty of Care: Dive professionals have a legal and ethical duty of care toward their divers. This implies that actions and inactions that may contribute to injury or death must be actively avoided and safety measures need to be proactively taken.

Maintaining thorough records of training, equipment maintenance, and dive plans is essential to demonstrate adherence to regulations and ethical standards. This documentation becomes invaluable in the unfortunate event of an incident.

Q 11. Explain the principles of buoyancy control in relation to dive rescue.

Buoyancy control is fundamental in dive rescue, influencing the diver’s ability to maneuver and assist others underwater. Imagine it like controlling a hot air balloon – precise adjustments are key to stable movement.

In a rescue scenario, maintaining neutral buoyancy allows the rescuer to effortlessly approach and assist the distressed diver without excessive effort or risk of uncontrolled movement. A rescuer needs to be capable of adjusting their buoyancy to ascend or descend quickly, smoothly, and safely, without affecting their own air supply or the integrity of the rescue.

Techniques like adding or removing air from the BCD, adjusting weighting, and skillful finning all play a role. A diver who is buoyant will be difficult to assist because of the upward force. The opposite will also make assistance difficult.

Furthermore, the rescuer needs to be aware of the buoyancy of the victim. An unconscious or panicked diver may have poor buoyancy control, requiring the rescuer to use additional techniques, such as holding the diver’s tank, or performing a controlled ascent with additional buoyant support. Competency in buoyancy control is the foundation of successful underwater rescue operations.

Q 12. What are the signs and symptoms of nitrogen narcosis?

Nitrogen narcosis, also known as ‘rapture of the deep,’ is a neurological condition caused by the increased pressure of nitrogen at depth, affecting the central nervous system. It’s like having a mild alcohol intoxication at depth, impairing judgment and cognitive function.

- Signs and Symptoms: The symptoms vary with depth and individual susceptibility but can include impaired judgment, euphoria, disorientation, slowed reactions, and increased confidence – often leading to risky behaviors, increased risk-taking, and neglecting safety procedures. Some divers report feeling lightheaded or experiencing hallucinations.

The best way to avoid nitrogen narcosis is to remain within safe depth limits, especially avoiding dives into the deeper zone. Proper training and awareness of symptoms are crucial for early recognition and prevention. A sudden change in behavior underwater should raise suspicion for the possible effect of nitrogen narcosis.

Q 13. How would you manage a diver suffering from oxygen toxicity?

Oxygen toxicity is a serious condition resulting from breathing high partial pressures of oxygen, primarily affecting the central nervous system and lungs. It’s like an overdose of oxygen, causing a range of detrimental effects.

Management of Oxygen Toxicity: The immediate action is to reduce the partial pressure of oxygen, which can often mean a controlled ascent to a shallower depth. It’s critical to ascend slowly and steadily to avoid decompression sickness.

The diver must be carefully monitored for further complications such as seizures, convulsions, or respiratory problems.

Once on the surface, immediate medical attention is necessary. Administering pure oxygen may seem counterintuitive, but in some cases, controlled oxygen therapy can help manage complications after oxygen toxicity is resolved. Emergency transport and professional hyperbaric treatment may be required depending on the severity of the condition. Prompt and correct action can prevent severe consequences and save a diver’s life.

Q 14. Describe the role of a dive safety officer during a dive operation.

A Dive Safety Officer (DSO) is responsible for overseeing all aspects of a dive operation, ensuring the safety and well-being of all divers. They are the safety net, the eyes and ears, checking everything is done correctly.

- Pre-Dive Planning: The DSO meticulously plans and reviews dive profiles, assessing environmental conditions, equipment checks, and diver experience levels. They ensure all divers are adequately trained and equipped.

- Emergency Response: The DSO is responsible for leading and coordinating the emergency response, using their expertise to assess the situation quickly and initiate the correct procedure, whether that’s initiating a rescue, initiating communication to emergency personnel, or initiating a safety stop.

- Risk Assessment: The DSO is responsible for identifying and mitigating potential risks, taking into account factors such as weather, water conditions, and dive location.

- Supervision: The DSO monitors the divers throughout the operation, ensuring they follow established safety procedures and guidelines.

- Post-Dive Procedures: After the dive, the DSO oversees decompression procedures, ensures that all divers are safely back on the surface and undertakes post-dive briefings for safety improvement.

The DSO is not just a supervisor; they’re a leader, an advisor, and a crucial element of a safe dive operation. Their role is instrumental in preventing accidents and ensuring effective response in case something goes wrong.

Q 15. What are the common causes of dive accidents?

Dive accidents stem from a multitude of factors, often interconnected. They can be broadly categorized into human error, equipment malfunction, and environmental hazards.

- Human Error: This is the most common cause. Examples include inadequate training, poor planning (e.g., neglecting to check weather conditions or dive site specifics), ignoring buddy procedures, exceeding personal limits (depth, bottom time, air consumption), and panic or poor decision-making underwater. For instance, a diver might underestimate their air consumption and surface with critically low air reserves, or fail to recognize the signs of nitrogen narcosis at depth.

- Equipment Malfunction: Faulty equipment, improper maintenance, or incorrect assembly can lead to serious problems. This could include regulator failure, BCD malfunction causing uncontrolled ascent or descent, or a leaking dry suit leading to hypothermia. Regular equipment checks and servicing are crucial to mitigate this.

- Environmental Hazards: These include strong currents, poor visibility, hazardous marine life (e.g., jellyfish stings, aggressive fish), sudden changes in weather, and unpredictable underwater topography. A diver caught in a strong current without adequate training might struggle to navigate back to the boat or surface safely.

It’s important to note that often, accidents are a combination of these factors. A diver might make a poor decision (human error) that is exacerbated by malfunctioning equipment. A comprehensive risk assessment before every dive is essential.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. How do you maintain situational awareness during a dive emergency?

Maintaining situational awareness during a dive emergency is paramount. It involves constantly monitoring your environment, your buddy’s condition, your own physical state, and your air supply. Think of it like being a pilot conducting a constant pre-flight checklist, even in the air.

- Regular Buddy Checks: Frequent visual and physical checks with your buddy, confirming their air supply, and general wellbeing.

- Environmental Monitoring: Constant observation of currents, visibility, depth, and the surrounding environment to anticipate and avoid potential hazards. This includes assessing the bottom for obstacles and paying attention to any changes in the water conditions.

- Self-Monitoring: Regularly checking your air supply, depth gauge, and compass, and paying attention to your own physical and mental state. Recognizing early warning signs of decompression sickness, nitrogen narcosis, or other dive-related illnesses is crucial.

- Communication: Clear and effective communication with your dive buddy is essential, using hand signals, and speaking clearly if within range. Using a dive slate can assist in emergencies where communication is difficult.

- Emergency Procedures: Knowledge and practice of emergency ascent procedures, including controlled ascents and dealing with equipment failure, are crucial.

Situational awareness isn’t just about reacting to events; it’s about proactively preventing them. By maintaining this vigilance throughout the dive, divers greatly reduce their risk of accidents.

Q 17. What are the different types of dive profiles and their implications for safety?

Dive profiles refer to the graphical representation of a dive, showing depth and time. Different profiles pose different safety implications.

- Simple Dive Profile: A straightforward descent to a specific depth, a period of bottom time, and a direct ascent. This is the safest profile for recreational divers.

- Multi-level Dive Profile: Involves multiple depths during a single dive. These can be more complex to plan and manage, increasing the risk of decompression sickness if not properly managed.

- Repetitive Dive Profile: Multiple dives within a short timeframe. This increases the risk of decompression sickness because the body doesn’t have enough time to off-gas nitrogen between dives. Proper dive interval planning and the use of dive tables or computers is essential here.

- Deep Dive Profile: Dives exceeding 30 meters (100 feet). These dives are significantly more dangerous due to increased risks of nitrogen narcosis, oxygen toxicity, and decompression sickness. Specialized training is required.

Understanding the implications of each profile allows divers to make informed choices, plan accordingly, and mitigate the risks associated with the dive.

Q 18. Explain the use of dive tables and dive computers.

Dive tables and dive computers are tools used to manage dive time and depth to minimize the risk of decompression sickness (DCS), also known as ‘the bends’.

Dive Tables: These are printed tables that provide a conservative estimate of safe no-decompression dive times at various depths. They are based on established decompression models and are relatively simple to use but lack the precision and flexibility of dive computers.

Dive Computers: These sophisticated electronic devices track dive parameters like depth, time, and ascent rate, calculating the diver’s tissue saturation and providing real-time feedback. They offer more personalized dive planning, adapt to changes in the dive profile, and provide warnings of potential DCS risks. They consider repetitive dives and are generally more accurate than dive tables.

Both tools aim to prevent DCS by ensuring adequate time for nitrogen to be eliminated from the body after a dive. However, dive computers offer enhanced safety and flexibility but require proper understanding and maintenance.

Q 19. What are the standard safety procedures for using scuba equipment?

Standard safety procedures for scuba equipment use are critical for safe diving. These procedures should be rigorously followed before, during, and after every dive.

- Pre-Dive Checks: A thorough equipment check, often following a specific checklist, is paramount. This includes verifying the proper functioning of the regulator, BCD, gauges, and other essential equipment.

- Buddy System: Never dive alone. Always dive with a qualified buddy, sharing responsibilities and ensuring mutual support.

- Proper Weighting: Appropriate weighting is crucial for safe buoyancy control. Incorrect weighting can lead to exhaustion and difficulty managing ascents and descents.

- Controlled Ascents and Descents: Slow and controlled ascents and descents are essential to prevent DCS. Rapid ascents can cause serious injury.

- Air Management: Careful monitoring of air supply and efficient air consumption are crucial to avoid running out of air underwater.

- Post-Dive Procedures: Proper rinsing and storage of equipment after each dive extends its lifespan and prevents damage.

Following these procedures significantly reduces the chances of equipment failure and ensures a safe diving experience.

Q 20. How do you ensure the safety of your dive team members?

Ensuring the safety of dive team members relies on proactive measures and adherence to established safety protocols.

- Pre-Dive Briefing: A thorough briefing covering dive plan, potential hazards, communication procedures, emergency procedures, and contingency plans.

- Buddy System Enforcement: Strict adherence to the buddy system, with regular buddy checks and close monitoring of each other’s wellbeing.

- Risk Assessment: Careful assessment of the dive site, weather conditions, and diver experience levels to identify and mitigate potential risks.

- Appropriate Training and Certification: Ensuring all members possess the necessary training and certification for the planned dive.

- Emergency Response Plan: A clearly defined emergency response plan, including communication procedures, emergency ascent techniques, and first aid protocols.

- Post-Dive Debriefing: A discussion after the dive to review the events, identify any issues, and learn from the experience.

A strong safety culture where divers prioritize safety, follow protocols, and support each other is essential for a safe dive operation. Remember that teamwork and communication are paramount.

Q 21. Describe your experience with emergency oxygen administration.

Emergency oxygen administration is a critical skill for dive rescue and emergency response. I have extensive experience administering emergency oxygen using both portable and fixed oxygen systems. This includes assessing the diver’s condition, selecting the appropriate mask or non-rebreather, ensuring proper oxygen flow, and monitoring the patient’s response.

My experience encompasses various scenarios including suspected decompression sickness, air embolism, and other dive-related emergencies. Proper training and certification in oxygen administration, along with frequent practice and drills, are critical to handling these potentially life-threatening situations effectively and efficiently.

I am proficient in recognizing the signs and symptoms of oxygen toxicity, and can adjust oxygen delivery accordingly to prevent adverse effects. Knowing when to initiate oxygen therapy and when to seek further medical attention is crucial. Proper documentation of oxygen administration, including time, flow rate, and the patient’s response is vital.

Q 22. Explain the proper techniques for performing CPR on a diver.

Performing CPR on a diver is similar to standard CPR, but with crucial considerations for the unique environment and potential injuries. The first step is always to ensure scene safety – is the diver still underwater? Are there any hazardous conditions? Once the diver is brought to a safe location and secured from further harm, we assess their airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs).

Airway: Open the diver’s airway using the head-tilt-chin-lift maneuver. Be cautious, as spinal injuries are a possibility, especially in diving accidents. If a suspected spinal injury exists, use the jaw-thrust maneuver instead. Clear any obstructions from the mouth and throat.

Breathing: Check for breathing. If not breathing or only gasping, immediately begin rescue breaths. Deliver two rescue breaths before starting chest compressions.

Circulation: Begin chest compressions at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute, pushing hard and fast. The depth of compressions should be at least 2 inches. Continue CPR until the diver regains consciousness, an AED becomes available, or emergency medical services (EMS) arrive. Consider the possibility of decompression sickness; rapid changes in altitude or movement could worsen the situation.

Important Considerations for Divers: Divers might have a pneumothorax (collapsed lung) or air embolism (air bubbles in the bloodstream), which can be aggravated by CPR. If possible, keep the diver’s head and torso aligned to minimize any such risk. Early access to hyperbaric oxygen therapy is crucial for decompression sickness.

Q 23. How do you manage a dive accident in a remote location?

Managing a dive accident in a remote location necessitates immediate, decisive action and efficient resource utilization. The acronym ‘RACE’ can be helpful: Rescue, Assess, Communicate, Evacuate.

- Rescue: Safely retrieve the diver from the water, prioritizing the safety of rescuers. Use appropriate equipment (e.g., dive rescue equipment, flotation devices).

- Assess: Quickly assess the diver’s condition, focusing on ABCs, signs of decompression sickness (DCS), and other injuries. Administer first aid as needed, and continue CPR if necessary. Note, in a remote location, advanced skills may need to be applied immediately given delayed help.

- Communicate: Contact emergency services as soon as possible via satellite phone or other available communication methods. Provide your exact location, number of divers involved, nature of the incident, and the diver’s condition.

- Evacuate: Plan and execute an evacuation strategy based on the diver’s condition and available resources. This might involve using a boat, helicopter, or other means of transport to reach a medical facility.

Essential Supplies: A remote dive kit should include a comprehensive first-aid kit with specific supplies for managing diving injuries, a satellite phone or other communication device, emergency oxygen, and appropriate signaling devices.

Q 24. How do you handle a conflict within a dive team?

Conflict within a dive team can be extremely dangerous, compromising safety and mission success. Addressing conflict requires diplomacy, clear communication, and a focus on teamwork. The first step is to identify the source of conflict. Is it a personality clash, differing opinions on dive procedures, equipment malfunction or simple fatigue?

Mediation: If possible, a team leader or experienced diver should facilitate open communication between the involved parties. This should be done in a private, safe space away from other divers.

Addressing the Root Cause: Explore the root of the issue. Is it a misunderstanding, differing expectations, or a procedural problem? Clearly establish the diving plan and roles. Addressing specific issues with equipment failure, for example, helps alleviate the problem.

Safety First: If the conflict cannot be resolved and it poses a risk to safety, the team leader has the authority to remove individuals from the diving operation. Prioritizing safety is paramount.

Post-Dive Debriefing: A post-dive debriefing is often a beneficial step to discuss the events and address team dynamics, promoting open communication and creating a more positive team atmosphere.

Q 25. Describe your experience with incident reporting and documentation.

Accurate and thorough incident reporting and documentation are critical for ensuring accountability, learning from mistakes, and improving safety procedures. My experience involves using a standardized reporting format that captures all pertinent information: date, time, location, individuals involved, equipment used, the nature of the incident, actions taken, injuries sustained, and outcomes. This usually follows a specific format, commonly used in the diving industry.

Detailed Documentation: The documentation is comprehensive, including detailed descriptions of the events leading up to, during, and after the incident. Photographs and videos, when possible and appropriate, support the written report.

Confidentiality: Maintaining confidentiality of personal information and following all relevant data protection regulations is essential.

Analysis and Improvement: The reported information is used for analysis, identifying areas where safety procedures can be improved. This could include retraining, equipment modifications, or changes to standard operating procedures.

Legal Considerations: Accurate and complete documentation is essential to mitigate potential legal liabilities following accidents or injuries.

Q 26. Explain your understanding of different types of diving equipment malfunctions.

Diving equipment malfunctions can range from minor inconveniences to life-threatening emergencies. Understanding the potential failure points of different equipment components is crucial for safe diving.

- Breathing Apparatus: Malfunctions can include regulator free-flows, low-pressure alarms, or complete system failure. Proper equipment checks and maintenance are vital.

- Buoyancy Compensators (BCs): Leaks, inflation/deflation issues, and harness failures can impact buoyancy control and safety. Regular inspections are crucial.

- Dive Computers: Battery failure, software glitches, or incorrect sensor readings can lead to dangerous decisions about dive profiles. Backup methods for depth and dive time monitoring should be considered.

- Exposure Protection: Suit leaks, tears, or loss of insulation can lead to hypothermia. Proper inspection and maintenance of the suit is essential.

- Other Equipment: Fins, masks, and other gear can fail due to wear and tear, leading to problems like impaired visibility or loss of propulsion.

Preventative Measures: Regular equipment maintenance, thorough pre-dive checks, and proper training significantly reduce the likelihood of equipment-related incidents.

Q 27. How do you maintain your own dive skills and certifications?

Maintaining dive skills and certifications requires a commitment to continuous learning and practice. My approach involves a combination of:

- Regular Diving: Consistent diving practice helps maintain proficiency in various dive conditions and environments. I try to dive frequently and in different conditions to keep my skills sharp.

- Continuing Education: Participating in refresher courses, specialized courses (e.g., rescue diver, technical diving), and workshops helps update knowledge and skills. This is vital in the constantly evolving world of dive equipment and techniques.

- Equipment Maintenance: Regular maintenance of my own equipment is vital to ensure that it is in perfect working order. It’s best to prevent problems before they arise.

- Professional Development: Attending industry conferences and seminars, reading trade publications, and staying updated on the latest safety standards and best practices are also key components.

- Physical Fitness: Maintaining a high level of physical fitness is crucial for safe diving, given the physical demands. This includes cardiovascular and strength training.

Q 28. Describe a challenging dive accident scenario you have encountered and how you handled it.

During a night dive in strong currents, a diver experienced a rapid loss of buoyancy and began ascending uncontrollably, potentially leading to a lung overexpansion injury. The diver had difficulty controlling their buoyancy compensator (BC) due to a malfunction of the inflation mechanism.

Immediate Actions: I immediately signaled other divers in the group, establishing an emergency ascent procedure. I quickly positioned myself alongside the ascending diver, providing physical assistance and helping them maintain a slower, controlled ascent. We brought the diver to the surface gently and administered emergency oxygen.

Post-Incident: Once on the surface, we conducted a thorough assessment, checking for injuries and symptoms of lung overexpansion. We then immediately informed our dive operation and commenced the appropriate emergency protocol for the situation, including communicating with the dive boat and other emergency services.

Lessons Learned: This incident highlighted the importance of thorough pre-dive checks and redundancy in equipment. We revised the standard operating procedures to include additional safety checks related to BC inflation mechanisms and emergency buoyancy control drills. It reinforced the need for continuous vigilance and strong team communication during diving operations.

Key Topics to Learn for Emergency Response and Dive Accident Management Interview

- Emergency Response Principles: Understanding incident command systems (ICS), risk assessment, scene safety procedures, and communication protocols.

- Dive Accident Recognition and Response: Identifying various dive-related emergencies (e.g., decompression sickness, air embolism, equipment failure), initiating appropriate emergency care, and coordinating rescue efforts.

- Dive Physiology and Medicine: Knowledge of the physiological effects of diving on the human body, the causes of diving injuries, and the principles of dive-related first aid and treatment.

- Rescue Techniques and Equipment: Proficiency in various dive rescue techniques (surface and underwater), understanding the operation and limitations of rescue equipment (e.g., surface-supplied air, recompression chambers).

- Legal and Regulatory Compliance: Familiarity with relevant regulations, reporting procedures, and legal responsibilities related to dive accidents and emergency responses.

- Practical Application: Scenario-based problem-solving, demonstrating the ability to apply theoretical knowledge to real-world emergency situations, including decision-making under pressure.

- Teamwork and Leadership: Understanding the importance of effective teamwork in emergency response, demonstrating leadership qualities and the ability to manage personnel during critical incidents.

- Documentation and Reporting: Accurate and detailed record-keeping of incidents, including incident reports, medical documentation, and communication logs.

Next Steps

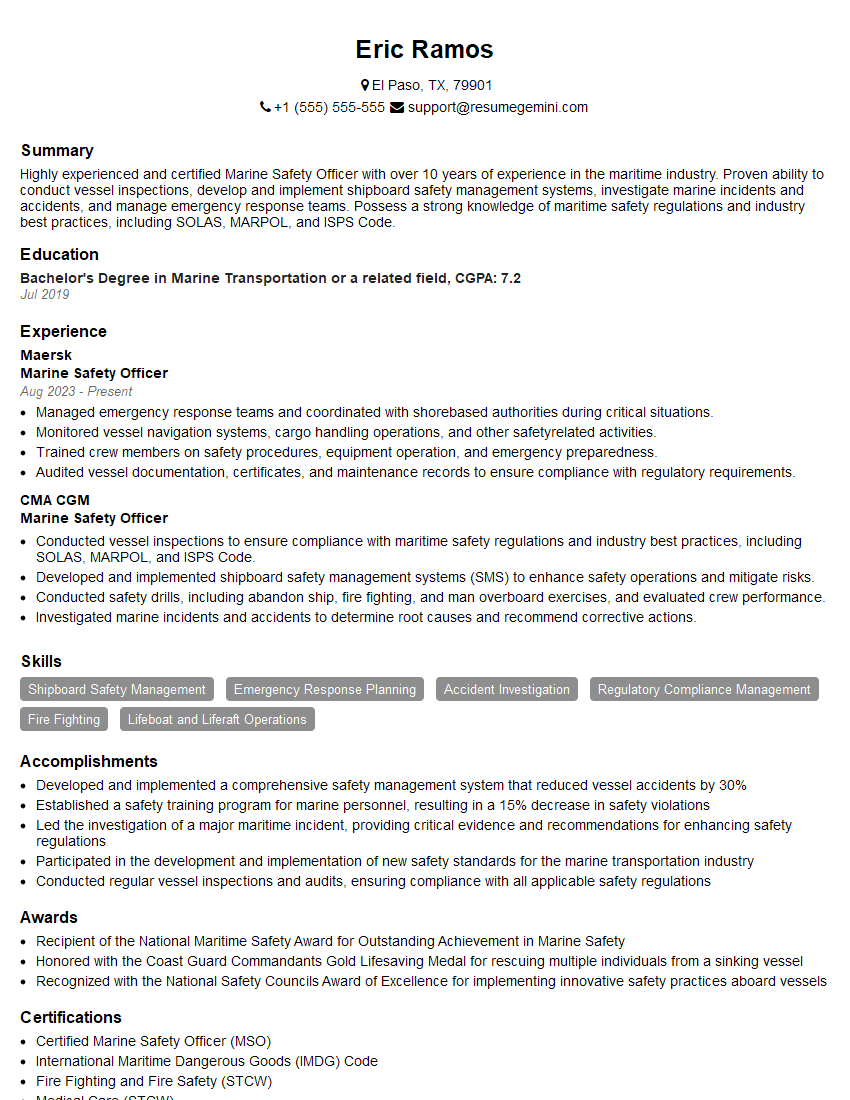

Mastering Emergency Response and Dive Accident Management opens doors to exciting and rewarding careers, offering opportunities for growth and specialization within the diving and safety industries. A strong resume is crucial for showcasing your skills and experience to potential employers. To maximize your job prospects, crafting an ATS-friendly resume is essential. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource that can help you build a professional and impactful resume, significantly improving your chances of landing your dream job. Examples of resumes tailored to Emergency Response and Dive Accident Management are available to guide you through the process.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

There are no reviews yet. Be the first one to write one.