Every successful interview starts with knowing what to expect. In this blog, we’ll take you through the top Gauging and Metrology interview questions, breaking them down with expert tips to help you deliver impactful answers. Step into your next interview fully prepared and ready to succeed.

Questions Asked in Gauging and Metrology Interview

Q 1. Explain the difference between accuracy and precision in measurement.

Accuracy and precision are two crucial aspects of measurement, often confused but distinct. Accuracy refers to how close a measurement is to the true or accepted value. Think of it like hitting the bullseye on a dartboard – a highly accurate measurement consistently lands near the center. Precision, on the other hand, describes how close multiple measurements are to each other, regardless of their proximity to the true value. Imagine throwing darts that all cluster tightly together, but far from the bullseye; this demonstrates high precision but low accuracy. A measurement can be precise without being accurate, and vice-versa. For instance, a poorly calibrated scale might consistently give readings 10 grams heavier than the actual weight (high precision, low accuracy), while repeated measurements using a different scale might vary widely, but occasionally get close to the real value (low precision, potentially moderate accuracy).

Example: Imagine weighing a 100g weight. An accurate scale would consistently read close to 100g. A precise scale might consistently read 101g (high precision, but only slightly inaccurate). A scale that gives random readings between 90g and 110g is neither accurate nor precise.

Q 2. Describe various types of gauging instruments and their applications.

Gauging instruments are tools used for precise measurements, often focused on specific dimensions or characteristics. They come in various types, each suited to different applications:

- Micrometers: These provide highly precise linear measurements, often to thousandths of an inch or micrometers. Used widely in machining and manufacturing for verifying part dimensions.

- Calipers: Offer less precision than micrometers but are more versatile. They come in various forms (vernier calipers, digital calipers) and measure internal, external, and depth dimensions. Common in many industries including woodworking and metalworking.

- Dial Indicators/Gauge Heads: Measure small displacements or variations in surface flatness. Used for checking runout, parallelism, and other aspects of part geometry, often integrated into fixtures.

- Plug Gauges and Ring Gauges: Used for go/no-go inspection of cylindrical parts, quickly determining if a part is within tolerance. Crucial in quality control and manufacturing.

- Height Gauges: Precisely measure vertical distances, frequently used in toolmaking and metrology laboratories.

- Thread Gauges: Used to inspect the dimensions of screw threads, ensuring they meet specifications.

- Optical Comparators: These instruments project an image of a part onto a screen, allowing for detailed comparison to a master drawing or template, ideal for complex shapes and intricate features.

The choice of gauging instrument depends heavily on the required precision, the type of measurement needed, and the application context.

Q 3. What are the common sources of measurement errors?

Measurement errors can stem from various sources, broadly categorized as:

- Environmental Factors: Temperature variations, humidity, and vibrations can all affect measurements. For instance, a steel ruler might expand slightly in higher temperatures, leading to inaccurate readings.

- Instrument Errors: These include inherent inaccuracies within the instrument itself, such as wear and tear on a micrometer, calibration drift in a digital device, or poor design leading to systematic errors.

- Operator Errors: Incorrect use of instruments (e.g., applying too much pressure to a caliper), parallax error (reading a scale from an angle), or misinterpretation of readings are all human factors that contribute to measurement error.

- Part Errors: The part being measured itself may have imperfections or variations that affect the measurement. This might include surface roughness, irregularities in shape, or deformations.

- Method Errors: The measurement process itself might contain flaws, for example, the choice of an inappropriate measurement technique or poor fixturing.

Understanding these sources helps in identifying and minimizing errors through proper instrument calibration, operator training, and controlled environmental conditions.

Q 4. How do you perform a gauge R&R study?

A Gauge R&R (Repeatability and Reproducibility) study assesses the variability in measurements obtained using a specific gauge by different operators. The goal is to determine how much of the total variation in measurements is due to the gauge itself (repeatability) and how much is due to differences between operators (reproducibility). This helps determine if the gauge is suitable for its intended application.

Steps involved:

- Select Parts: Choose a representative sample of parts, spanning the expected range of measurements.

- Select Operators: Include all operators who will use the gauge.

- Measurements: Each operator measures each part multiple times (typically 2-3 repetitions per part per operator).

- Data Analysis: Statistical methods (e.g., ANOVA) are used to analyze the data and partition the variation into components: repeatability (variation within an operator’s measurements), reproducibility (variation between operators), and part-to-part variation.

- Interpretation: The results are expressed as %GRR (%Gauge R&R) – the percentage of total variation attributed to the gauge and operators. Generally, a %GRR of less than 10% is considered acceptable. A higher %GRR indicates significant variation due to the measurement system and suggests either improving the gauge or training operators.

Software packages are commonly used for Gauge R&R analysis, simplifying the calculations and providing clear visualizations of the results.

Q 5. Explain the concept of statistical process control (SPC) in metrology.

Statistical Process Control (SPC) in metrology involves using statistical techniques to monitor and control the measurement process. It aims to identify and address sources of variation, ensuring measurements are consistent and reliable. Control charts are a cornerstone of SPC, graphically displaying measurements over time. These charts allow for the detection of trends, shifts, or other unusual patterns that may indicate a problem in the measurement process (e.g., instrument drift, operator error). Examples include X-bar and R charts (for monitoring average and range of measurements), and individuals and moving range charts (for individual measurements).

In metrology, SPC helps:

- Ensure measurement accuracy and precision: By identifying and addressing variations, SPC helps minimize errors.

- Monitor gauge performance: Tracking measurements over time helps detect when a gauge needs recalibration or repair.

- Improve process efficiency: Identifying and correcting issues early in the measurement process prevents wasted time and materials.

- Support compliance: Many quality management systems (e.g., ISO 9001) require the use of SPC for process monitoring and control.

SPC is not merely about detecting problems but also about preventing them. Regular monitoring and analysis, using control charts, allow for proactive identification and correction of variations before they significantly affect product quality.

Q 6. How do you calibrate measurement instruments?

Calibrating measurement instruments is crucial for ensuring their accuracy. It involves comparing the instrument’s readings to a known standard of higher accuracy. The process typically involves:

- Selecting Standards: Choose traceable standards with a higher accuracy than the instrument being calibrated.

- Establishing a Controlled Environment: Maintain stable temperature and humidity to minimize environmental effects on measurements.

- Performing Measurements: Make multiple measurements using both the instrument being calibrated and the standard, over the full range of the instrument.

- Comparing Readings: Analyze the differences between the instrument’s readings and the standard’s readings.

- Adjustments (if necessary): Some instruments allow for adjustments to compensate for discrepancies. This might involve adjusting a micrometer’s zero setting or modifying the calibration parameters of a digital gauge.

- Documentation: Meticulously document the calibration process, including the date, the standards used, the measurements, any adjustments made, and the results. This documentation provides a traceable record of the instrument’s accuracy.

Calibration frequency depends on several factors: instrument type, usage frequency, criticality of measurements, and environmental conditions. A calibration certificate should be issued after successful calibration, indicating the instrument’s accuracy and the validity period.

Q 7. What are the different types of coordinate measuring machines (CMMs)?

Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) are used to precisely measure the three-dimensional coordinates of points on an object. Different types exist, categorized primarily by their measuring probe and structure:

- Contact CMMs: These use a physical probe to touch the part surface, measuring the coordinates of each contact point. They offer high accuracy and are suitable for a wide range of applications. Subtypes within this category include bridge-type, cantilever-type, and horizontal-arm CMMs based on their physical structure.

- Non-contact CMMs: These use optical or laser scanning techniques to measure the part without physical contact. They are faster than contact CMMs and are suitable for measuring fragile or complex shapes. Optical CMMs might use laser triangulation or white-light scanning.

- Hybrid CMMs: Combine contact and non-contact measurement technologies to leverage the advantages of both approaches.

The selection of a CMM depends on factors such as part complexity, required accuracy, measurement speed, and budget. Choosing the right type is crucial for efficient and accurate dimensional inspection.

Q 8. Describe your experience with CMM programming and operation.

My experience with CMM (Coordinate Measuring Machine) programming and operation spans over [Number] years, encompassing various machine types and applications. I’m proficient in programming using both manual methods (e.g., creating measurement routines point-by-point) and using CAD model-based programming. This allows me to efficiently measure complex geometries with high accuracy.

For example, in a recent project involving the inspection of a complex automotive part, I developed a CMM program that automatically measured over 200 features, including dimensions, angles, and surface roughness, generating a comprehensive report within minutes. The program incorporated advanced features like automated probing and feature recognition to reduce measurement time and enhance precision. I also have experience with various probing systems, including touch-trigger, scanning, and optical probes, selecting the most appropriate technique depending on part geometry and material.

Furthermore, my operational experience includes routine maintenance, calibration checks, and troubleshooting of CMMs. I understand the importance of ensuring the machine’s accuracy and reliability through proper operation and preventative maintenance procedures. I am familiar with various software packages used in CMM operation and data analysis.

Q 9. How do you handle measurement uncertainties?

Handling measurement uncertainties is crucial for ensuring the reliability of measurement results. This involves understanding and quantifying all sources of uncertainty, from the instrument itself (e.g., resolution, repeatability) to environmental factors (e.g., temperature, humidity) and operator variability. We utilize a combination of methods to address this:

- Calibration and Traceability: Regularly calibrating the measuring instruments against traceable standards minimizes instrument-related uncertainties.

- Statistical Analysis: Repeating measurements multiple times and applying statistical methods (e.g., calculating standard deviations) helps identify and quantify random errors.

- Uncertainty Budgeting: This systematic approach involves identifying and quantifying all significant sources of uncertainty and combining them to determine the overall measurement uncertainty. The result is often expressed as an expanded uncertainty, typically using a coverage factor of 2 or 3, which gives a confidence interval around the measured value.

- Environmental Control: Maintaining a stable environment helps minimize environmental influences on measurement results.

For example, when measuring a critical dimension on a precision part, a detailed uncertainty budget would be prepared, considering uncertainties from the CMM’s calibration, probe wear, temperature variations, and operator technique. This allows us to state the measurement result with a clearly defined uncertainty, enabling a reliable assessment of whether the part meets specifications.

Q 10. Explain the importance of traceability in metrology.

Traceability in metrology is essential for ensuring the reliability and comparability of measurement results. It establishes an unbroken chain of comparisons linking a measurement to a known standard, typically national or international standards. This chain provides confidence that measurements made at different times and locations are consistent and meaningful.

Think of it like a family tree for your measurements. Each measurement is linked to a previous calibration or standard, going all the way back to a primary standard maintained by a national metrology institute. Without traceability, it’s difficult to verify the accuracy of measurements, making it challenging to compare results from different labs or over time. This is especially crucial in regulated industries like aerospace or medical devices, where accurate and reliable measurements are critical for safety and quality.

Traceability is documented through calibration certificates which provide information on the measurement equipment used, the standards employed, and the uncertainties associated with the calibration process. This documentation is vital for demonstrating compliance with industry standards and regulations.

Q 11. What are the common standards and specifications used in your field?

The field of gauging and metrology relies heavily on international and national standards. Some of the most common include:

- ISO 9001: Quality management systems, providing a framework for quality control and assurance.

- ISO 10012: Measurement management systems, specifying requirements for establishing, implementing, and maintaining a measurement management system.

- ASME Y14.5: Dimensioning and tolerancing standards for engineering drawings. This is crucial for interpreting and verifying part specifications.

- VIM (International Vocabulary of Metrology): Defines key metrological terms and concepts, ensuring consistent understanding and communication within the field.

- National standards from various countries (e.g., ANSI in the US, BS in the UK) often provide more specific guidelines or adaptations of international standards.

These standards guide best practices for measurement, calibration, and data analysis, ensuring consistency and reliability across different organizations and applications.

Q 12. Describe your experience with different types of gauges (e.g., plug gauges, ring gauges).

I have extensive experience with various types of gauges, including plug gauges, ring gauges, snap gauges, and dial indicators. My experience covers the use, inspection, and calibration of these instruments.

Plug gauges and ring gauges are used for verifying the diameter of cylindrical features. I understand the importance of selecting the appropriate gauge tolerance grades (e.g., GO/NO-GO) to ensure effective and reliable inspection. I am proficient in using these gauges, ensuring proper insertion and identifying whether a part falls within the acceptable tolerance range. For example, in an automotive engine component inspection, we’d use a series of plug gauges to ensure the precise dimensions of a critical bore to prevent engine failure. Incorrect dimensions could lead to leaks or improper fit.

Snap gauges provide a quicker assessment of whether a part is within tolerance. Dial indicators are versatile and offer precise measurements of various features, including linear displacement, run-out, and parallelism. My experience also includes using other gauging techniques like optical comparators or profilometers for more complex geometry.

Q 13. How do you interpret measurement data and identify trends?

Interpreting measurement data and identifying trends involves a combination of visual inspection, statistical analysis, and an understanding of the manufacturing process. I typically start by visually reviewing the data to identify any obvious outliers or inconsistencies. Then I use statistical tools to analyze the data further.

For instance, control charts are extremely useful for identifying trends and detecting shifts in process performance. Histograms can illustrate the distribution of measurement data, highlighting potential issues like excessive variability or bias. I’d look for patterns such as:

- Increasing or decreasing trends: Indicating potential tool wear, process drift, or other systemic issues.

- Cyclical patterns: Often related to machine vibrations or periodic maintenance intervals.

- Outliers: Suggesting potential errors in measurement or unexpected variations in the manufacturing process.

The understanding of the manufacturing process is crucial, as this context helps interpret the data meaningfully. A single outlier might be a fluke, or it might signal a significant problem. The investigation would depend on the pattern and context. By combining statistical analysis with process knowledge, we can accurately identify the root causes of variations and implement corrective actions.

Q 14. What are your preferred methods for data analysis and reporting?

My preferred methods for data analysis and reporting involve the use of statistical software packages like Minitab or JMP, and spreadsheet software like Excel. I also utilize specialized CMM software for data processing and report generation. The choice depends on the complexity of the data and the specific requirements of the project.

My reports typically include:

- Summary statistics: Mean, standard deviation, range, etc., providing a clear overview of the measurement data.

- Graphical representations: Histograms, control charts, scatter plots, etc., to visually communicate the data trends and patterns.

- Uncertainty analysis: A clear statement of the measurement uncertainty associated with the results.

- Conclusions and recommendations: A concise summary of the findings and recommendations for corrective actions, if necessary.

Clear, concise reporting is crucial for effective communication of findings. My reports are designed to be easily understood by both technical and non-technical audiences, ensuring that the information is readily accessible and actionable.

Q 15. Explain your understanding of tolerance analysis.

Tolerance analysis is a crucial process in engineering and manufacturing that determines the acceptable variations in dimensions and characteristics of a part or assembly. It helps ensure that components fit together correctly and function as intended. Essentially, it’s about quantifying how much deviation from the ideal design is still acceptable without compromising performance or safety.

The process usually involves identifying all dimensions, analyzing their individual tolerances, and using statistical methods to predict the overall variation in the final assembly. This often includes considering the worst-case scenario (stacking tolerances) and more statistically-based approaches like root-sum-square (RSS) calculations to predict the overall variation. For instance, if you’re assembling a shaft and a hole, the tolerance analysis will determine the range of shaft and hole diameters that will ensure the shaft fits within the hole without excessive clearance or interference.

Software tools play a significant role in simplifying tolerance analysis, allowing engineers to quickly assess the impact of dimensional variations on the assembly. The output of tolerance analysis directly influences design decisions, manufacturing processes, and inspection procedures.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Describe your experience working with GD&T (Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing).

I have extensive experience with GD&T, utilizing it throughout my career to effectively communicate design intent and ensure product quality. My proficiency extends beyond simple understanding of the symbols; I can apply GD&T principles to complex assemblies and leverage its power to control form, orientation, location, and runout.

For example, I’ve successfully used GD&T to define the acceptable position of a critical component in a high-precision medical device assembly. By specifying position tolerances using a datum reference frame, we minimized ambiguity and ensured consistent assembly. This not only simplified the manufacturing process but also significantly reduced the risk of assembly errors and potential product failures.

I’m also experienced in using GD&T analysis software to simulate the effects of tolerances on the assembly, helping to identify potential issues early in the design phase and preventing costly rework later on.

Q 17. How do you ensure the accuracy and reliability of measurement results?

Ensuring the accuracy and reliability of measurement results is paramount. My approach is multifaceted and relies on several key strategies:

- Calibration: Regular calibration of all measurement instruments against traceable standards is fundamental. This guarantees the instruments are functioning within their specified accuracy limits. I maintain meticulous calibration records and follow strict procedures.

- Environmental Control: Measurements are highly sensitive to environmental factors like temperature and humidity. Controlling these factors is critical. I always operate within stable environmental conditions or apply appropriate compensation techniques.

- Measurement Methods: Selecting the right measurement technique for the task is essential. I ensure that the method chosen is suitable for the part’s geometry, material, and required accuracy. This involves understanding the limitations and uncertainties associated with each technique.

- Statistical Process Control (SPC): Implementing SPC techniques allows for continuous monitoring of measurement data. By tracking trends and identifying patterns, we can detect potential issues early on and prevent them from affecting the product quality.

- Operator Training: Proper training of measurement personnel is vital to minimize human error. I ensure all operators are well-trained in the use of instruments and the appropriate measurement techniques.

Combining these strategies enables us to maintain high confidence in the reliability and accuracy of the measurement results.

Q 18. Describe a time you had to troubleshoot a measurement issue.

In a previous project involving the measurement of complex surface profiles on a turbine blade, we encountered consistently inconsistent results. The initial measurements exhibited significant variations, far exceeding the acceptable tolerance.

My troubleshooting process involved:

- Identifying the Source: I systematically reviewed the entire measurement process, including the instrument setup, calibration, environmental conditions, and operator technique.

- Data Analysis: A thorough analysis of the measurement data revealed a non-random pattern, suggesting a problem with the probe setup or the instrument itself.

- Verification: We re-calibrated the instrument and meticulously checked its setup against the manufacturer’s specifications. We also verified the stability of the environmental conditions.

- Solution: We discovered a slight misalignment in the probe, which was causing the inconsistent measurements. After correcting the alignment, we obtained consistent and reliable results within the acceptable tolerance.

This experience highlighted the importance of systematic troubleshooting and the need for a thorough understanding of the measurement system and its potential sources of error.

Q 19. How familiar are you with different types of measurement software?

I’m proficient with various measurement software packages, including CMM software (e.g., PC-DMIS, CALYPSO), optical measurement software (e.g., for laser scanners), and other specialized metrology software. My experience extends to data acquisition, analysis, report generation, and statistical analysis of the measurement data. I can readily adapt to new software packages as needed, focusing on functionality relevant to the project.

For instance, I frequently utilize PC-DMIS for CMM programming and data analysis, generating detailed inspection reports to assess part conformance to specifications. Similarly, I’ve utilized optical metrology software to process scan data from 3D laser scanners for reverse engineering and surface quality analysis.

Q 20. Describe your experience with different material testing methods related to gauging.

My experience with material testing methods related to gauging encompasses various techniques used to assess material properties relevant to gauging performance and part quality. This includes tensile testing, hardness testing, and surface roughness measurement.

Tensile testing provides insights into the material’s strength and ductility, crucial for understanding the gauge’s robustness and lifespan. Hardness testing helps determine the gauge’s resistance to wear and deformation. Measuring surface roughness is important for evaluating the gauge’s interaction with the measured part, and ensuring accuracy.

I understand the importance of selecting appropriate testing methods based on the material type and the specific gauging application. For example, selecting the right hardness testing method (Rockwell, Brinell, Vickers) depends on the material’s hardness range.

Q 21. Explain your understanding of measurement system analysis (MSA).

Measurement System Analysis (MSA) is a critical process used to evaluate the accuracy and precision of a measurement system. It helps determine if the measurement system is capable of providing reliable data for its intended use. The goal is to identify and quantify sources of variation within the measurement system, ensuring that variations in the measurements are due to actual differences in the part, not inaccuracies in the measurement process itself.

Common MSA studies include Gauge Repeatability and Reproducibility (GR&R) studies, which analyze the variation due to different operators, different gauges, and part-to-part variation. These studies use statistical methods to quantify the measurement system’s capability, often expressed as a percentage of tolerance or a signal-to-noise ratio. If the measurement system is found to be inadequate, MSA helps identify the sources of error, which may include instrument calibration, operator training, or environmental factors.

A well-executed MSA is crucial for ensuring the reliability of data used in quality control, process improvement, and other critical decision-making processes.

Q 22. How do you maintain and care for gauging equipment?

Maintaining gauging equipment is crucial for accurate measurements and reliable results. It’s a multi-faceted process encompassing regular cleaning, calibration, and proper storage. Think of it like maintaining a high-precision instrument – a slight misalignment can drastically alter your findings.

- Cleaning: Regular cleaning removes dirt, debris, and oils that can affect the gauge’s accuracy. The cleaning method depends on the gauge material and design; some may require specialized cleaning solutions, while others can be wiped down with a lint-free cloth. Always consult the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Calibration: This is the most critical aspect. Gauges need to be calibrated against traceable standards at regular intervals (frequency determined by usage and the gauge’s sensitivity). This ensures the gauge readings are accurate and compliant with industry standards. Calibration certificates serve as documentation of this process.

- Storage: Gauges should be stored in a clean, controlled environment to prevent damage and maintain accuracy. This includes protecting them from extreme temperatures, humidity, and physical damage. Proper storage also helps to extend the lifespan of the equipment.

- Regular Inspection: Visual inspections should be performed before each use, checking for signs of damage, wear, or misalignment. This proactive approach helps identify potential problems before they affect the measurements.

For example, in a manufacturing setting where I worked, we had a strict calibration schedule for our micrometers and calipers, with traceability to national standards. Failure to follow the calibration schedule resulted in a stop-work order until the gauges were recalibrated, ensuring product quality.

Q 23. Describe your experience with laser scanning technology.

Laser scanning technology offers highly accurate and efficient dimensional measurement. My experience includes using laser scanners for various applications, including reverse engineering, quality control, and rapid prototyping.

I’ve worked with both contact and non-contact laser scanners. Non-contact scanners are particularly beneficial for complex geometries and delicate parts, where traditional methods might be impractical or cause damage. They provide a point cloud representing the part’s surface, from which dimensional data is extracted through software analysis.

For instance, in a project involving intricate turbine blades, laser scanning proved invaluable. The speed and precision of the scan allowed us to create a precise digital model for analysis and comparison against CAD designs, highlighting any deviations much faster than manual methods.

I am proficient in various software packages used for processing and analyzing the point cloud data, extracting critical dimensions, and generating reports.

Q 24. What is your experience with automated gauging systems?

I have extensive experience with automated gauging systems, which significantly enhance efficiency and precision in measurement processes. These systems can automate various tasks, from part handling and measurement to data analysis and reporting, reducing manual effort and eliminating human error.

My experience encompasses the integration and operation of various automated systems, including coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) with automated probing systems, vision-based gauging systems, and robotic-assisted gauging cells. I’m familiar with programming and troubleshooting these systems, ensuring optimal performance and accurate results.

For example, in a previous role, I helped implement an automated gauging system for inspecting automotive components. This system significantly reduced inspection time and improved consistency, leading to a reduction in scrap and rework.

I also possess expertise in selecting appropriate automated gauging solutions based on specific application requirements, considering factors such as part geometry, throughput requirements, and budget constraints.

Q 25. How familiar are you with quality management systems (e.g., ISO 9001)?

I am very familiar with quality management systems, particularly ISO 9001. My experience includes working within organizations that are certified to this standard and actively participating in maintaining compliance. I understand the principles of ISO 9001, including its requirements for quality management, internal audits, and continuous improvement.

My understanding extends beyond just knowing the standards; I’ve actively contributed to the development and implementation of quality procedures, documented processes, and ensuring traceability of measurement data. This ensures compliance not just with ISO 9001 but also with specific industry standards relevant to the types of gauging activities undertaken.

I’m adept at using statistical process control (SPC) techniques to monitor process capability and identify potential issues before they lead to non-conforming products.

Q 26. Explain your experience with root cause analysis related to measurement problems.

Root cause analysis (RCA) is vital when dealing with measurement discrepancies. My approach utilizes structured methodologies such as the 5 Whys, fishbone diagrams, and fault tree analysis to identify the underlying causes of measurement problems.

I start by clearly defining the problem – for instance, a consistent bias in measurements from a particular gauge. Then, I systematically investigate possible causes, considering factors such as gauge calibration, environmental conditions, operator technique, and part variations. This involves gathering data, analyzing trends, and eliminating potential causes until the root cause is identified.

In one instance, a recurring measurement problem was traced to inconsistent clamping pressure on a part during measurement using a CMM. By implementing a standardized clamping procedure, the problem was resolved.

My RCA experience involves the creation of corrective and preventative actions (CAPAs) to prevent similar problems from recurring. This involves implementing process improvements, updating work instructions, and enhancing operator training.

Q 27. Describe your experience with different types of surface finish measurement techniques.

Surface finish measurement is crucial for many applications, and I’m experienced in various techniques. The choice of technique depends on the specific requirements, including the material, the desired level of detail, and the available budget.

- Profilometry: This technique uses a stylus to physically traverse the surface, providing a 3D profile. This method is suitable for a variety of materials and offers high resolution, but it can be time-consuming and may damage delicate surfaces.

- Optical Techniques: Techniques such as confocal microscopy and optical profilometry offer non-contact measurements, providing high-resolution surface profiles without damaging the part. They are ideal for delicate or complex surfaces.

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): AFM offers the highest resolution, providing nanoscale surface characterization. This technique is suitable for very fine surface features, but it is more complex and expensive.

- Surface Roughness Measurement Instruments: These instruments, such as contact roughness testers (using a stylus) and non-contact optical roughness testers, provide surface roughness parameters like Ra, Rz, and others. These are widely used in quality control to ensure surface quality meets specifications.

My experience includes using all these techniques and interpreting the resulting data to determine whether the surface finish meets the specified requirements. I understand the different surface roughness parameters and their significance in different applications.

Q 28. What are your salary expectations?

My salary expectations are commensurate with my experience and skills, and are in line with the industry standard for a domain expert in Gauging and Metrology with my qualifications. I am open to discussing a competitive compensation package that reflects the value I bring to your organization. I would be happy to provide a specific range after learning more about the details of the position and the company’s compensation structure.

Key Topics to Learn for Gauging and Metrology Interview

- Dimensional Metrology: Understanding various measurement techniques (e.g., linear, angular, surface roughness), their principles, and limitations. Consider the impact of different measurement uncertainties.

- Gauging Principles: Explore the design and application of various gauges (e.g., plug gauges, ring gauges, snap gauges), including their tolerances and acceptance criteria. Practice calculating gauge tolerances and understanding their role in quality control.

- Statistical Process Control (SPC): Learn how to interpret control charts, calculate process capability indices (Cp, Cpk), and understand their implications for manufacturing processes. Be prepared to discuss how SPC relates to gauging and metrology.

- Calibration and Traceability: Understand the importance of calibration standards and traceability to national or international standards. Be ready to discuss calibration procedures and the impact of calibration uncertainty.

- Measurement System Analysis (MSA): Familiarize yourself with methods for evaluating the accuracy, precision, and stability of measurement systems. Be able to discuss the impact of measurement errors on product quality.

- Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs): Understand the operation and applications of CMMs, including different probing techniques and data analysis methods. Be prepared to discuss the advantages and limitations of CMMs compared to other gauging methods.

- Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T): Gain a solid understanding of GD&T symbols and their application in defining part tolerances. Be able to interpret GD&T specifications and their implications for manufacturing and inspection.

- Practical Application: Be prepared to discuss real-world examples of how gauging and metrology principles are applied in various industries (e.g., automotive, aerospace, medical device manufacturing).

- Problem-Solving: Practice identifying and troubleshooting measurement problems, including the analysis of measurement errors and the development of corrective actions.

Next Steps

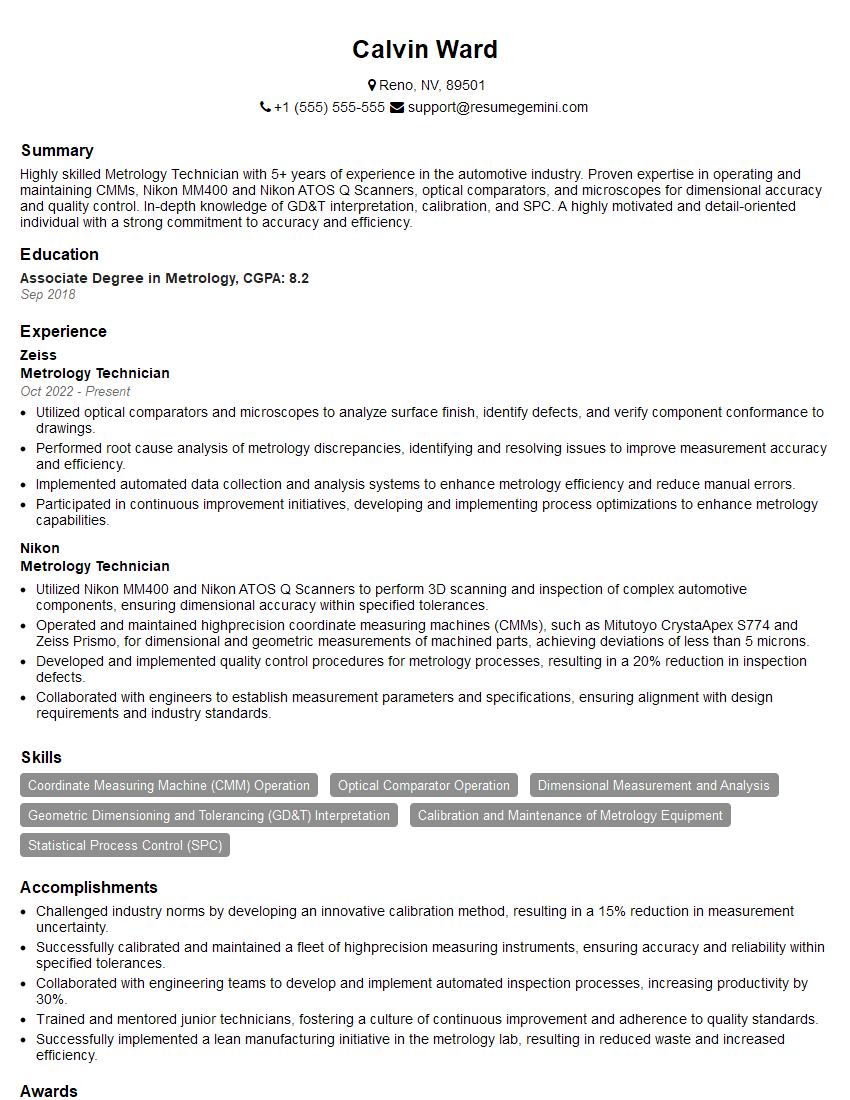

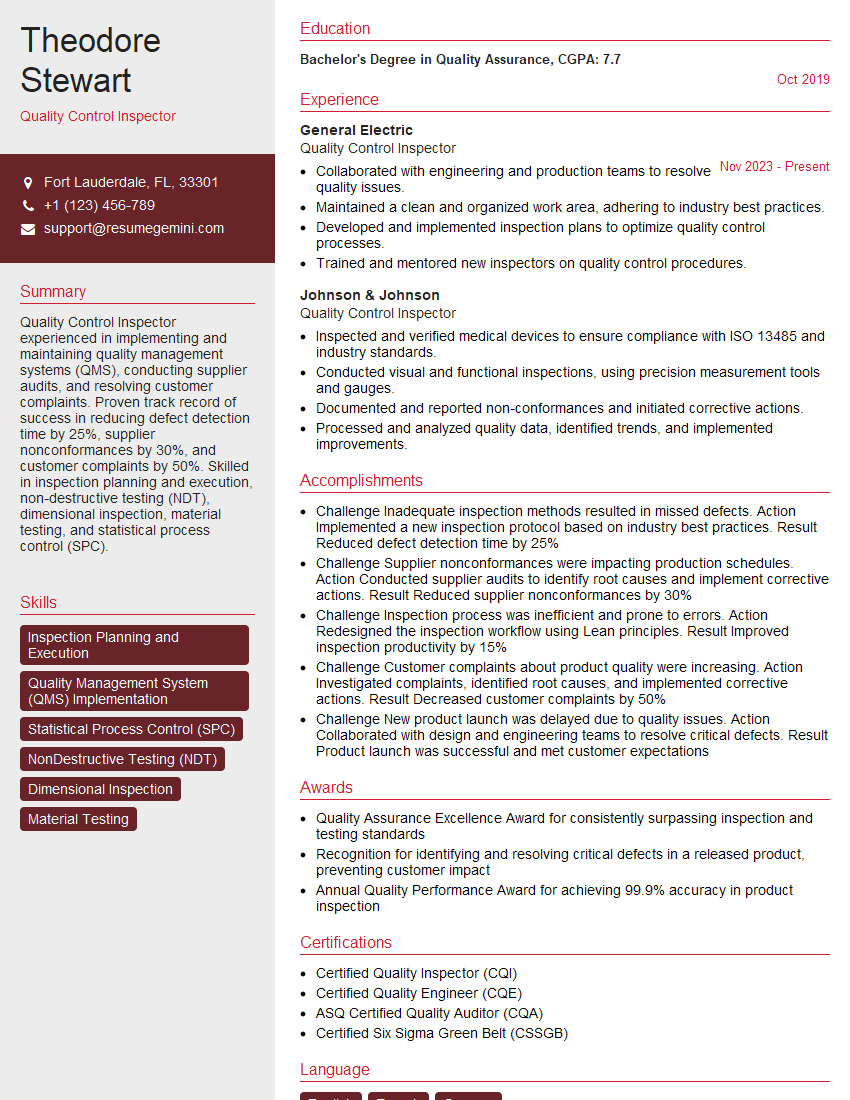

Mastering Gauging and Metrology opens doors to exciting career opportunities in quality control, manufacturing, and engineering. A strong understanding of these principles is highly valued by employers and can significantly boost your career prospects. To increase your chances of landing your dream job, it’s crucial to create an ATS-friendly resume that effectively showcases your skills and experience. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource that can help you build a professional and impactful resume. They provide examples of resumes tailored to the Gauging and Metrology field, ensuring your application stands out from the competition. Take the next step and craft a winning resume today!

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO