Every successful interview starts with knowing what to expect. In this blog, we’ll take you through the top Knowledge of Metallurgy and Heat Treatment interview questions, breaking them down with expert tips to help you deliver impactful answers. Step into your next interview fully prepared and ready to succeed.

Questions Asked in Knowledge of Metallurgy and Heat Treatment Interview

Q 1. Explain the difference between ferrous and non-ferrous metals.

The primary difference between ferrous and non-ferrous metals lies in their iron content. Ferrous metals contain iron as their primary constituent, often with carbon as a significant alloying element. This results in materials that are generally strong, but can also be prone to corrosion. Examples include steel (an alloy of iron and carbon) and cast iron (a higher-carbon iron alloy). Non-ferrous metals, on the other hand, do not contain iron as their primary element. They often possess properties like better corrosion resistance, higher electrical conductivity, or specific color characteristics. Examples include copper, aluminum, zinc, and titanium. The choice between ferrous and non-ferrous metals depends heavily on the application’s requirements – strength versus corrosion resistance, for instance.

Think of it like this: if you need something strong and relatively inexpensive for construction, a ferrous metal like steel is likely your choice. But, if you need something corrosion-resistant for electrical wiring, then copper, a non-ferrous metal, is the superior option.

Q 2. Describe the iron-carbon equilibrium diagram and its significance.

The iron-carbon equilibrium diagram, also known as the phase diagram, is a graphical representation of the phases present in iron-carbon alloys at different temperatures and carbon concentrations. It’s crucial in metallurgy because it predicts the microstructure and thus the properties of steel at various temperatures and compositions. The diagram shows regions where austenite (FCC structure), ferrite (BCC structure), pearlite (a layered structure of ferrite and cementite), cementite (Fe3C), and other phases exist.

Its significance lies in its ability to guide heat treatments. By understanding the diagram, metallurgists can predict the microstructural changes that occur during processes like heating and cooling, allowing them to tailor the properties (strength, ductility, hardness) of steel for specific applications. For example, by understanding the eutectoid point (0.77% carbon), we know that cooling slowly from the austenite region will produce pearlite, a relatively ductile material; whereas, rapid cooling (quenching) can trap the carbon in austenite, forming martensite – a very hard but brittle structure.

Q 3. What are the different types of heat treatments and their applications?

Heat treatments are processes that involve controlled heating and cooling of metals to alter their microstructure and, consequently, their mechanical properties. Different types include:

- Annealing: Relieves internal stresses and improves ductility (discussed in detail later).

- Normalizing: Refines the grain structure, improving mechanical properties.

- Hardening (Quenching): Rapid cooling from the austenite phase to produce a hard martensitic structure (discussed later).

- Tempering: A low-temperature heating of hardened steel to reduce brittleness and improve toughness (discussed later).

- Carburizing: Increasing the carbon content of the surface of steel to increase hardness and wear resistance.

- Nitriding: Diffusing nitrogen into the surface to create a hard, wear-resistant case.

Applications vary wildly: hardening gears to withstand wear, annealing components after manufacturing to release stresses, and tempering tools to achieve a balance between hardness and toughness.

Q 4. Explain the process of annealing and its effects on material properties.

Annealing is a heat treatment process involving heating a metal to a specific temperature, holding it there for a sufficient time, and then cooling it slowly (usually in a furnace). The purpose is to relieve internal stresses and improve ductility. Internal stresses can build up during manufacturing processes like forging, casting, or machining. These stresses can lead to distortion, cracking, or premature failure.

The effects of annealing depend on the specific annealing type (e.g., stress-relief annealing, full annealing, process annealing). In general, annealing reduces hardness, increases ductility, and improves machinability. For example, annealing a severely cold-worked metal will soften it, making it easier to deform further. In practical terms, imagine forging a metal part – it will be stressed after the forging process. Annealing helps to eliminate those stresses, enhancing the part’s durability and reducing the risk of cracks.

Q 5. What is quenching and what factors influence the effectiveness of quenching?

Quenching is a rapid cooling process, typically involving submerging a heated metal into a quenching medium like oil, water, or polymer solutions. The purpose is to transform austenite into martensite, a hard and brittle phase. The effectiveness of quenching depends on several factors:

- Quenchant type: Different quenchants have different cooling rates. Water cools faster than oil, resulting in a more complete martensitic transformation, but also increasing the risk of cracking.

- Part geometry: Complex shapes cool unevenly, leading to residual stresses and potential cracking. Thicker sections retain heat longer, resulting in incomplete martensite formation.

- Quenchant temperature: Higher quenchant temperatures generally reduce cooling rate.

- Alloy composition: Hardenability, which is the ability of an alloy to form martensite, is directly affected by the composition of the metal. Steels with higher carbon and alloying element content exhibit higher hardenability.

For instance, a small, simple part can be quenched in water effectively; however, a large, complex part might require oil quenching to prevent cracking. Choosing the correct quenchant and monitoring the process is vital for achieving the desired hardness without compromising part integrity.

Q 6. Describe the process of tempering and its impact on material hardness and toughness.

Tempering is a low-temperature heat treatment applied to hardened steel (usually martensite) to reduce brittleness and improve toughness. Hardened steel, while extremely hard, is very brittle and prone to cracking under impact. Tempering involves reheating the hardened steel to a temperature below the lower critical temperature (Ac1), holding it at that temperature for a specific time, and then allowing it to cool. This process reduces residual stresses and causes the martensite to transform partially into more ductile phases such as tempered martensite and bainite.

The impact on hardness and toughness is significant: tempering decreases hardness but drastically improves toughness, making the material more resistant to fracture. This balance between hardness and toughness is critical in many applications. Think of a knife blade: it needs to be hard enough to hold an edge but also tough enough to withstand impacts without chipping. Tempering allows us to achieve this balance.

Q 7. Explain the concept of hardenability and its importance in heat treatment.

Hardenability refers to the ability of a steel alloy to form martensite in its interior during quenching. It’s not simply a measure of how hard a steel can become, but rather a measure of how *deep* the hardened martensitic layer will penetrate into a component after quenching. A steel with high hardenability will form a deep hardened layer, even in large sections, while a steel with low hardenability will only have a thin hardened surface layer. Hardenability is heavily influenced by the chemical composition of the steel, particularly the carbon content and the presence of alloying elements such as chromium, molybdenum, nickel and manganese.

Its importance in heat treatment is paramount because it dictates the choice of steel for a given application. For example, a large gear requiring hardness throughout its section needs a steel with high hardenability to ensure that the interior is also hardened adequately. On the other hand, a thin part that needs a surface hardness only might use a steel with lower hardenability, avoiding potential cracking during quenching. Hardenability is determined using tests like the Jominy test, which helps predict how a given steel will harden under specific quenching conditions.

Q 8. What are the different types of steel and their respective applications?

Steel is an alloy primarily of iron and carbon, with other elements added to modify its properties. The type and amount of these alloying elements drastically alter the steel’s characteristics, leading to a vast array of applications.

- Carbon Steel: The simplest form, containing up to 2% carbon. Higher carbon content increases strength and hardness but reduces ductility. Applications include tools, machinery components, and structural elements. Think of the steel in a simple wrench or a bridge beam. The amount of carbon dictates the specific application.

- Alloy Steel: Carbon steel enhanced with other elements like chromium, nickel, manganese, molybdenum, and vanadium. These additions improve properties such as strength, corrosion resistance, hardenability, and toughness. Stainless steel, a common example, contains chromium for excellent corrosion resistance, making it suitable for cutlery, medical instruments, and architectural elements. High-speed steel, containing tungsten and molybdenum, retains hardness at high temperatures, essential for cutting tools.

- Tool Steel: High-carbon alloy steels designed for tools requiring high hardness, wear resistance, and toughness. Examples include high-speed steel used in drills and milling cutters, and cold work tool steel used in punches and dies.

- Stainless Steel: A family of alloy steels with at least 10.5% chromium, resulting in excellent corrosion resistance. There are various grades, like austenitic (non-magnetic, easily formable) used in kitchen appliances and ferritic (magnetic, more brittle) used in automotive parts.

The choice of steel depends on the required properties for a specific application. For instance, a surgeon’s scalpel needs corrosion-resistant stainless steel, whereas a structural beam might use high-strength low-alloy steel.

Q 9. Explain the principles of phase transformations in metals.

Phase transformations in metals involve changes in the crystal structure and/or composition. These are driven by changes in temperature and/or pressure. Imagine it like water: it can exist as ice (solid), water (liquid), and steam (gas), each with different structures and properties. Similarly, metals can exist in different phases (like austenite, ferrite, pearlite), each with unique crystal structures and properties.

A crucial example is the iron-carbon diagram, which illustrates the phases present in steel at different temperatures and carbon concentrations. Heating or cooling a steel will cause it to transition between these phases, leading to changes in microstructure and therefore mechanical properties. For example, austenite is a high-temperature phase of iron-carbon that is face-centered cubic (FCC). Upon cooling, it can transform into ferrite (body-centered cubic – BCC) and pearlite (a mixture of ferrite and cementite). This transformation process, if controlled carefully through heat treatment (like annealing, quenching, tempering), allows us to tailor the properties of the steel to meet our needs.

The kinetics of these transformations – how fast they occur – are also essential. Rapid cooling (quenching) can trap high-temperature phases that are otherwise metastable, leading to hard, martensitic structures. Slower cooling allows for equilibrium phases to form.

Q 10. Describe different non-destructive testing (NDT) methods used in metallurgy.

Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods are crucial for evaluating the integrity of metallic components without causing damage. Various techniques are employed, each with its strengths and weaknesses:

- Visual Inspection: The simplest method, involving careful visual examination for surface defects like cracks, corrosion, or dimensional inaccuracies.

- Liquid Penetrant Testing (LPT): A dye is applied to the surface to reveal surface-breaking flaws. The dye penetrates the flaw, and a developer draws it to the surface, making it visible.

- Magnetic Particle Testing (MPT): Used for ferromagnetic materials. Magnetic particles are applied to the surface, and a magnetic field is induced. Flaws disrupt the magnetic field, causing the particles to accumulate at the flaw, making it visible.

- Ultrasonic Testing (UT): High-frequency sound waves are transmitted into the material. Reflections from internal flaws are detected and analyzed to determine the flaw’s size, location, and orientation. This method is excellent for detecting internal flaws.

- Radiographic Testing (RT): X-rays or gamma rays are passed through the material. Flaws attenuate the radiation differently than the surrounding material, creating shadows on a film or digital detector, revealing internal flaws.

- Eddy Current Testing (ECT): Uses electromagnetic induction to detect surface and near-surface flaws in conductive materials. An alternating current induces eddy currents in the material, and flaws disrupt these currents, which is detected by a probe.

The choice of NDT method depends on the material, the type of flaw expected, and the access to the component.

Q 11. What are the common causes of metal failure and how can they be prevented?

Metal failure is a catastrophic event that can result from various causes. Understanding these causes is crucial for preventing failures.

- Yielding: Permanent deformation occurs when the material is stressed beyond its yield strength. This can be prevented by using materials with higher yield strengths or by designing components to remain within the elastic region.

- Fracture: Separation of the material into two or more pieces. Brittle fracture occurs suddenly with little or no plastic deformation, often due to high stress concentrations or low temperatures. Ductile fracture involves significant plastic deformation before failure. Proper material selection (tough materials), stress relieving heat treatments, and good design practices are key preventive measures.

- Fatigue: Failure under cyclic loading at stresses lower than the yield strength. Fatigue cracks initiate at stress concentrations and propagate gradually until failure occurs. Preventing fatigue involves reducing stress concentrations (smooth surfaces, appropriate design), using fatigue-resistant materials, and proper maintenance.

- Creep: Time-dependent deformation under sustained stress at elevated temperatures. This is often seen in high-temperature applications such as power plant components. Creep can be prevented by using creep-resistant materials or by limiting the operating temperature and stress.

- Corrosion: Degradation of material due to chemical or electrochemical reactions. Corrosion protection involves surface treatments (coating, plating), material selection (corrosion-resistant alloys), and environmental control.

Preventive measures often involve a combination of material selection, design considerations, and process controls.

Q 12. How do you determine the grain size of a metal?

Grain size determination is essential for understanding and controlling the mechanical properties of metals. Several methods exist:

- Microscopic Method: A polished and etched sample is examined under an optical or electron microscope. The average grain size is determined by counting the number of grains in a known area or by measuring the average intercept length of grain boundaries.

- Comparison Chart Method: The microstructure is compared visually to a standardized chart with different grain sizes. This method is quicker but less precise than the microscopic method.

The grain size is often expressed using ASTM grain size number or average grain diameter. Smaller grain sizes generally result in higher strength and hardness but lower ductility.

Q 13. Explain the concept of grain boundary and its influence on material properties.

Grain boundaries are the interfaces between individual grains (crystals) in a polycrystalline material. They are regions of atomic mismatch, where the crystal lattice is disordered.

Grain boundaries significantly influence material properties:

- Strength: Grain boundaries impede the movement of dislocations, increasing strength and hardness. Finer grain sizes (more grain boundaries) lead to higher strength.

- Ductility: Grain boundaries can act as barriers to dislocation movement, reducing ductility. However, they can also provide paths for deformation at higher temperatures.

- Creep resistance: Grain boundaries act as diffusion paths for atoms, leading to creep at high temperatures. Controlling grain size and boundary character is crucial for creep resistance.

- Corrosion: Grain boundaries can be sites for preferential corrosion attack because of their higher energy state and different composition.

Understanding grain boundary characteristics is crucial for controlling material properties. Techniques like grain refinement (reducing grain size through heat treatments) are used to enhance the mechanical properties.

Q 14. Describe the different types of corrosion and their prevention methods.

Corrosion is the deterioration of a material due to chemical or electrochemical reactions with its environment. Different types exist:

- Uniform Corrosion: Occurs uniformly over the entire surface. It’s predictable and relatively easy to manage.

- Galvanic Corrosion: Occurs when two dissimilar metals are in contact in an electrolyte. The more active metal corrodes preferentially. Preventing this involves using dissimilar metals that are compatible or by using insulating materials to separate them.

- Pitting Corrosion: Localized corrosion that leads to small pits or holes. It’s difficult to detect and can lead to catastrophic failure. Material selection, surface treatments, and inhibitors can help prevent it.

- Crevice Corrosion: Occurs in narrow crevices or gaps where oxygen access is restricted. Stagnant solutions within the crevice become more aggressive. Good design to avoid crevices and appropriate sealing are key preventive measures.

- Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC): Occurs when a metal is subjected to tensile stress in a corrosive environment. The combination of stress and corrosion leads to crack initiation and propagation.

- Intergranular Corrosion: Corrosion occurring preferentially along grain boundaries. It weakens the material significantly. Proper heat treatments and material selection are crucial in mitigating this type of corrosion.

Corrosion prevention methods involve material selection (stainless steels, corrosion-resistant alloys), protective coatings (paint, plating, anodizing), cathodic protection (applying a protective current), and corrosion inhibitors (chemicals added to the environment to reduce corrosion rate).

Q 15. What is the significance of microstructure analysis in metallurgy?

Microstructure analysis is absolutely fundamental in metallurgy because it reveals the internal structure of a material, which directly dictates its macroscopic properties. Think of it like this: a building’s strength depends not just on the quantity of bricks but also on how they are arranged. Similarly, a metal’s strength, ductility, toughness, and other properties are directly related to the arrangement of its grains, phases, and defects at the microscopic level.

We use techniques like optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to visualize these microstructures. For instance, analyzing the grain size can tell us about the metal’s strength – smaller grains generally mean higher strength because they impede dislocation movement (a type of crystal defect that leads to deformation). The presence of certain phases or precipitates can also significantly alter properties; for example, carbides in steel contribute to hardness and wear resistance. By understanding the microstructure, we can tailor processing parameters and material selection to meet specific application needs.

For example, in designing a high-strength component for an aircraft, we’d carefully analyze the microstructure to ensure it possesses the required yield strength, tensile strength, and fatigue resistance, as well as the appropriate level of ductility to avoid brittle fracture.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Explain the role of alloying elements in modifying the properties of metals.

Alloying elements are the secret sauce of metallurgy! They are added to base metals to dramatically modify their properties. This is done by altering the microstructure and influencing factors like solid solubility, phase transformations, and the formation of intermetallic compounds.

Consider the classic example of steel: adding carbon to iron changes its properties from soft and ductile (pure iron) to hard and strong (steel). Carbon atoms occupy interstitial sites in the iron lattice, hindering dislocation movement and thus increasing strength and hardness. Different carbon percentages result in different steel grades, each with unique properties tailored to specific applications.

Other alloying elements, such as chromium, nickel, molybdenum, and vanadium, further refine properties. Chromium enhances corrosion resistance (stainless steel), nickel boosts toughness and ductility, molybdenum improves high-temperature strength, and vanadium strengthens and refines the grain structure. Understanding the interaction between alloying elements and the base metal allows for the precise tailoring of materials for various engineering challenges, from creating lightweight yet strong aerospace alloys to designing corrosion-resistant components for chemical plants.

Q 17. What are the different types of casting processes?

Casting is a fundamental manufacturing process involving pouring molten metal into a mold, allowing it to solidify into the desired shape. Many different casting processes exist, each with its own advantages and limitations:

- Sand Casting: The oldest and most versatile method. Molten metal is poured into a sand mold, which is then broken to remove the casting. Simple and cost-effective, but surface finish and dimensional accuracy are limited.

- Die Casting: Molten metal is injected under high pressure into a reusable metal mold (die). Produces high-quality castings with excellent dimensional accuracy and surface finish, but requires expensive tooling.

- Investment Casting (Lost-Wax Casting): A wax pattern is created and coated with a ceramic mold. The wax is melted out, and molten metal is poured into the mold. Allows for intricate designs and excellent surface finish.

- Centrifugal Casting: Molten metal is poured into a spinning mold. Centrifugal force distributes the metal evenly, resulting in dense and uniform castings.

The choice of casting process depends on factors such as the complexity of the part, required accuracy, material properties, and production volume. A simple component might be suitable for sand casting, whereas a complex, high-precision component would benefit from investment casting or die casting.

Q 18. Explain the process of forging and its advantages.

Forging is a metal forming process where a metal workpiece is compressed and shaped using localized compressive forces. Think of a blacksmith hammering a piece of metal on an anvil: that’s forging!

The process can be done using hammers, presses, or other specialized equipment. The metal is heated to a suitable temperature (for easier deformation and to avoid cracking) and then shaped by controlled deformation. This process refines the grain structure, resulting in enhanced strength, ductility, and fatigue resistance. The improved fiber flow aligns the grains along the direction of loading, further increasing strength in that specific direction.

Advantages of Forging:

- Increased strength and toughness due to grain refinement and fiber flow.

- Improved fatigue and impact resistance.

- Excellent dimensional accuracy and surface finish, especially with precision forging techniques.

- Ability to produce complex shapes.

Forged components are found in critical applications like automotive crankshafts, aircraft landing gear, and other high-stress components where reliability and strength are paramount.

Q 19. Describe the process of rolling and its applications.

Rolling is a metal forming process that reduces the thickness of a metal workpiece by passing it through a set of rollers. Imagine rolling out dough with a rolling pin – similar concept, but on a much larger scale and with much greater force!

The process can be used to produce sheets, plates, strips, and other forms of flat metal products. Different rolling techniques exist, such as hot rolling (at elevated temperatures) and cold rolling (at room temperature). Hot rolling allows for greater deformation, resulting in larger reductions in thickness, while cold rolling produces improved surface finish, tighter dimensional tolerances, and higher strength due to work hardening.

Applications of Rolling:

- Production of sheets and plates for automotive bodies, construction, and appliances.

- Manufacturing of rails for railways.

- Creating tubes and pipes for various applications.

- Producing thin foils for packaging and electronic applications.

The versatility of rolling makes it a cornerstone of the metal manufacturing industry, supplying a wide range of products essential to modern life.

Q 20. What are the different types of welding processes?

Welding is a fundamental joining process that fuses two or more metal pieces together using heat, pressure, or a combination of both. Many types of welding processes exist, categorized by their heat source and joining method:

- Arc Welding (SMAW, GMAW, GTAW): Uses an electric arc to generate the heat needed to melt the metal. SMAW (Shielded Metal Arc Welding) uses a consumable electrode coated with flux; GMAW (Gas Metal Arc Welding) uses a continuous wire electrode; and GTAW (Gas Tungsten Arc Welding) uses a non-consumable tungsten electrode. Each varies in efficiency, precision, and application.

- Resistance Welding (Spot Welding, Seam Welding): Uses electric resistance to generate heat at the joint, melting the metal and fusing the pieces together. Common for joining sheet metal.

- Gas Welding (Oxy-fuel Welding): Uses a mixture of oxygen and fuel gas (acetylene) to produce a flame for melting the metal. Versatile but slower than arc welding.

- Laser Welding: Employs a high-powered laser beam to precisely melt and fuse the metal. Allows for very precise and deep welds.

The selection of a welding process depends on several factors, including the thickness of the materials, the type of metal, the required joint strength, and the desired weld quality. For instance, spot welding is ideal for joining thin sheet metal in automotive production, while GTAW offers excellent control and quality for critical components.

Q 21. Explain the importance of understanding material properties in selecting appropriate materials for a specific application.

Understanding material properties is absolutely crucial in selecting the right material for a specific application. This is because the performance and longevity of any component or structure depend heavily on the material’s ability to withstand the expected operating conditions.

Consider the design of a bridge: we wouldn’t use a material with low tensile strength or poor fatigue resistance; instead, high-strength steel or even advanced composite materials are chosen to guarantee safety and durability under anticipated loads and environmental factors. Similarly, designing a component for a high-temperature environment requires choosing a material with excellent creep resistance and high-temperature strength. A biocompatible material is essential in medical implants, requiring consideration of aspects like corrosion resistance and the absence of toxic release.

Material property considerations encompass mechanical properties (strength, ductility, hardness, fatigue resistance), physical properties (density, melting point, thermal conductivity), and chemical properties (corrosion resistance, reactivity). A thorough understanding of these properties, coupled with detailed analysis of the operating conditions, guarantees the selection of a material that meets design criteria and ensures reliable operation, longevity and safety.

Q 22. Describe the different types of surface treatments and their applications.

Surface treatments modify the surface properties of a material, like hardness, corrosion resistance, or wear resistance, without significantly altering the bulk properties. Several types exist, each with specific applications:

- Carburizing: Diffuses carbon into the surface of low-carbon steel, increasing surface hardness. This is crucial for components requiring high wear resistance like gears and camshafts. For example, a car transmission gear uses carburizing to withstand the high stresses and friction during operation.

- Nitriding: Diffuses nitrogen into the surface, forming hard nitrides. It results in high surface hardness and excellent wear and fatigue resistance, often used in tools and engine components. Think of the increased durability of a precision cutting tool achieved through nitriding.

- Chromizing: Diffuses chromium into the surface, enhancing corrosion and oxidation resistance at high temperatures. This is commonly applied to parts operating in harsh environments like exhaust manifolds or furnace components. Imagine the extended lifespan of a furnace element in a power plant thanks to chromizing.

- Shot peening: Bombards the surface with small metallic shots, inducing compressive residual stresses. This significantly improves fatigue life and is frequently used in aircraft components and springs. The reduced risk of fatigue failure in an airplane wing is a direct benefit of shot peening.

- Anodizing: An electrochemical process that forms a thick oxide layer on aluminum, providing excellent corrosion protection and aesthetic appeal. Used widely in architectural applications and consumer electronics. The durable, corrosion-resistant finish on your aluminum laptop is a result of anodizing.

Q 23. Explain the concept of stress-strain curve and its importance in material characterization.

The stress-strain curve graphically represents a material’s response to an applied tensile load. The x-axis shows strain (deformation) and the y-axis shows stress (force per unit area). Its importance lies in characterizing a material’s mechanical properties:

- Young’s Modulus (Elastic Modulus): The slope of the initial linear portion represents the material’s stiffness – how much it deforms under stress. A steeper slope means higher stiffness.

- Yield Strength: The stress at which plastic deformation begins. Beyond this point, the material will not return to its original shape after the load is removed.

- Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS): The maximum stress the material can withstand before failure (fracture).

- Ductility: The ability of a material to deform plastically before fracture, represented by the elongation and reduction in area.

- Toughness: The material’s ability to absorb energy before fracture, represented by the area under the stress-strain curve.

Understanding these properties is crucial for selecting appropriate materials for engineering applications. For instance, designing a bridge requires a material with high yield strength and good ductility to withstand loads without failure.

Q 24. How do you interpret a tensile test report?

A tensile test report provides crucial data about a material’s mechanical properties. Key parameters to interpret include:

- Yield Strength: Indicates the stress at which permanent deformation begins.

- Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS): The maximum stress the material can withstand before failure.

- Elongation (%): The percentage increase in length after fracture, indicating ductility.

- Reduction in Area (%): The percentage decrease in cross-sectional area after fracture, another measure of ductility.

- Young’s Modulus: The material’s stiffness.

- Hardness: Often included, indicating resistance to indentation.

By comparing these values to material specifications, one can assess whether the material meets the required standards. For example, a low yield strength in a structural steel would indicate a serious quality issue.

Q 25. What is fatigue failure and how can it be prevented?

Fatigue failure is the progressive and localized structural damage that occurs when a material is subjected to cyclic loading (repeated stress). It leads to cracks that eventually propagate until complete fracture, even if the maximum stress is well below the material’s yield strength. Imagine repeatedly bending a paperclip – eventually it will break even though you’re not applying a huge force at once.

Preventing fatigue failure involves:

- Proper Material Selection: Choose materials with high fatigue strength.

- Stress Reduction: Reduce the magnitude of cyclic stresses by design modifications.

- Surface Treatments: Shot peening or other surface treatments can introduce compressive residual stresses, improving fatigue life.

- Good Design Practices: Avoid stress concentrations (sharp corners, holes) that act as crack initiation sites.

- Regular Inspection and Maintenance: Detect and address cracks before they propagate to failure.

Q 26. Explain the concept of creep and its implications in high-temperature applications.

Creep is the time-dependent deformation of a material under a constant load at elevated temperatures. Imagine a metal slowly stretching over time under a constant weight at a high temperature. This is essentially creep.

Implications in high-temperature applications are significant:

- Dimensional Changes: Components can deform, potentially leading to malfunction or failure. Turbine blades in jet engines are a prime example; creep can cause them to lose their aerodynamic shape.

- Reduced Strength: Prolonged creep weakens the material, reducing its load-carrying capacity.

- Fracture: In severe cases, creep can lead to fracture, causing catastrophic failure.

Mitigation strategies include using creep-resistant materials (e.g., high-temperature alloys), reducing operating temperatures, or applying design modifications to minimize stress.

Q 27. Describe your experience with specific heat treatment equipment and processes.

My experience encompasses a wide range of heat treatment equipment and processes. I’ve worked extensively with:

- Various Furnaces: Box furnaces, bell furnaces, pit furnaces, and controlled atmosphere furnaces for processes like annealing, hardening, tempering, and carburizing.

- Quenching Systems: Oil baths, water baths, polymer quenching systems, and air cooling to control cooling rates during heat treatment.

- Induction Heating Systems: For localized and rapid heating of components.

- Salt Baths: For specific heat treatments like nitriding.

I’m proficient in using data acquisition systems to monitor and control temperature profiles during heat treatment cycles, ensuring consistent and repeatable results. For instance, I’ve programmed and optimized numerous automated heat treatment cycles for improved efficiency and product quality.

Q 28. How do you troubleshoot problems related to heat treatment processes?

Troubleshooting heat treatment problems involves a systematic approach:

- Analyze the Problem: Identify the specific issue (e.g., inadequate hardness, distortion, cracking). Is the problem consistent across all parts or localized?

- Review Process Parameters: Check temperature profiles, heating and cooling rates, atmosphere control, and other process variables.

- Inspect the Equipment: Ensure furnace operation is within specifications, checking for malfunctions in heating elements, temperature sensors, or controllers.

- Material Analysis: Conduct metallurgical analysis (e.g., microstructural examination, hardness testing) to determine the root cause of the problem.

- Implement Corrective Actions: Based on the analysis, adjust process parameters, repair equipment, or change materials as needed.

For example, if parts are exhibiting excessive distortion after heat treatment, it may indicate an issue with the cooling rate or the presence of stress concentrators in the design.

Key Topics to Learn for Your Metallurgy and Heat Treatment Interview

Ace your next interview by mastering these essential concepts. Remember, understanding the “why” behind the processes is just as important as the “how.”

- Phase Diagrams: Understanding equilibrium diagrams, lever rule applications, and their implications for material properties and heat treatment processes. Think about how different phases influence mechanical behavior.

- Iron-Carbon Diagram: Deep dive into the key phases (austenite, ferrite, pearlite, cementite), their transformations, and the impact on steel properties. Consider practical examples like the heat treatment of different steel grades.

- Heat Treatment Processes: Mastering annealing, normalizing, hardening, tempering, and their effects on microstructure and mechanical properties. Be ready to discuss case hardening techniques and their applications.

- Alloying and its Effects: Explore how different alloying elements modify the properties of metals. Prepare to discuss the impact of specific elements (e.g., chromium, nickel, molybdenum) on steel characteristics.

- Mechanical Testing: Understand tensile testing, hardness testing, impact testing, and their relevance in evaluating material properties after heat treatment. Be prepared to interpret results and relate them to microstructure.

- Failure Analysis: Learn to identify common failure mechanisms in metallic components (e.g., fatigue, creep, stress corrosion cracking) and relate them to material selection and heat treatment practices.

- Non-Destructive Testing (NDT): Familiarize yourself with common NDT methods used to evaluate the quality and integrity of heat-treated components. Consider discussing examples like ultrasonic testing or magnetic particle inspection.

- Practical Applications: Be ready to discuss real-world applications of metallurgy and heat treatment in various industries (automotive, aerospace, manufacturing, etc.). Prepare examples of how heat treatment improves performance or solves specific engineering problems.

Next Steps: Unlock Your Career Potential

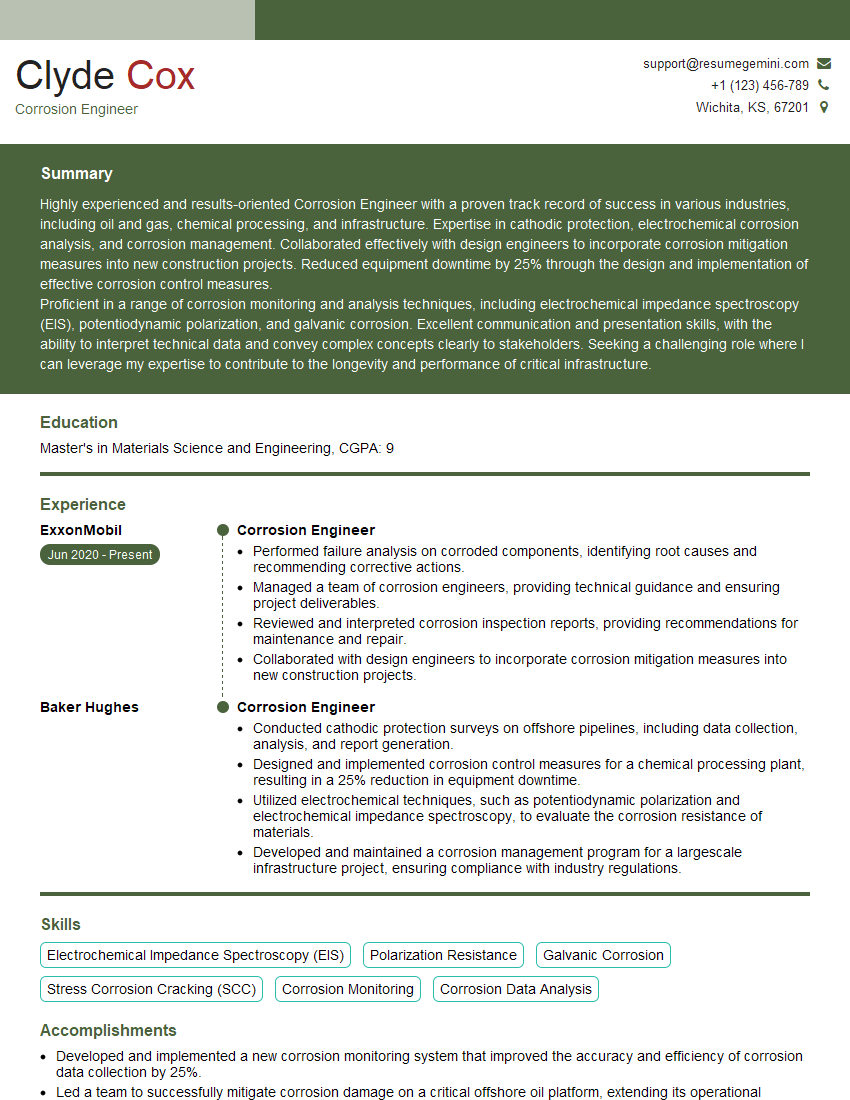

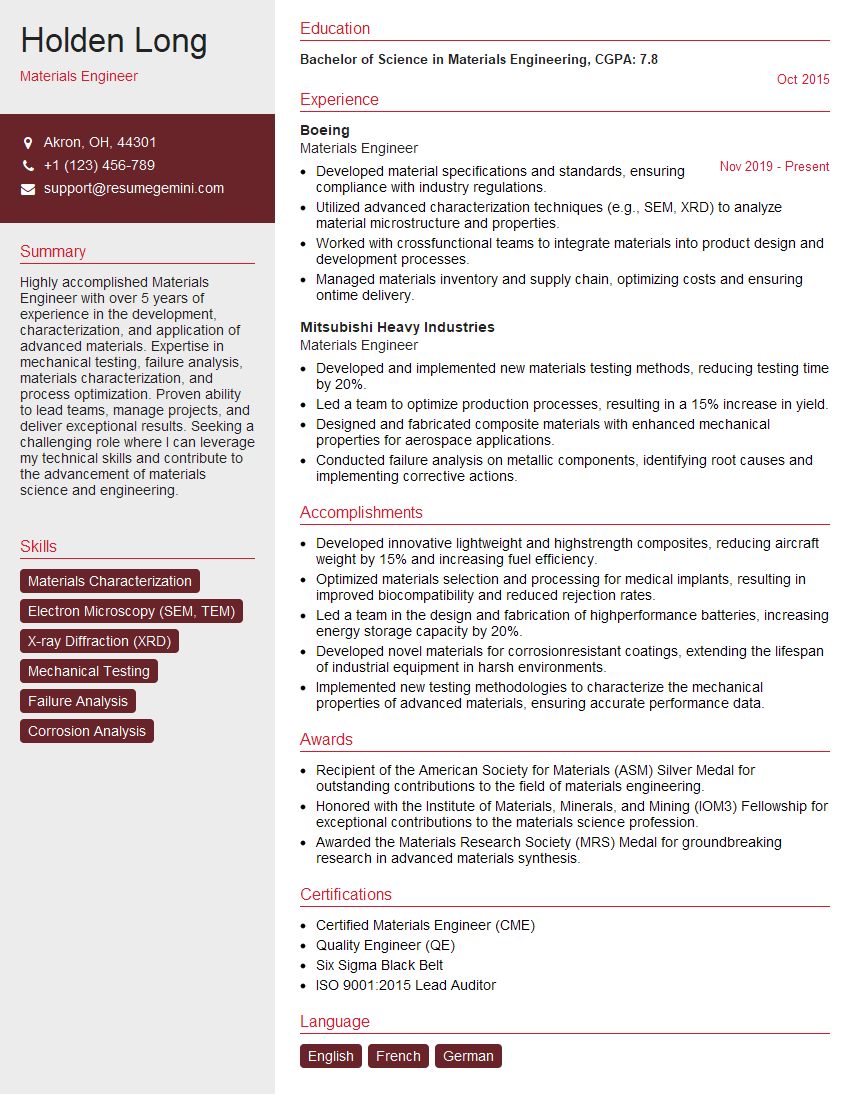

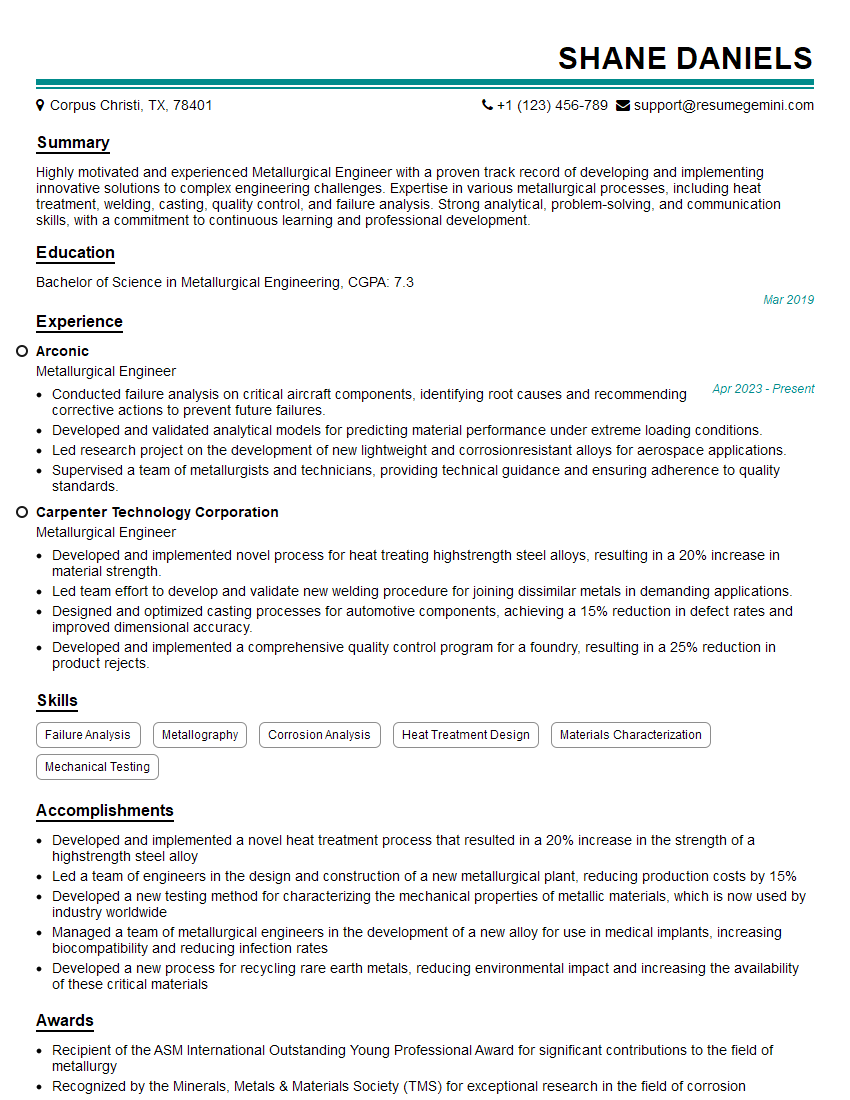

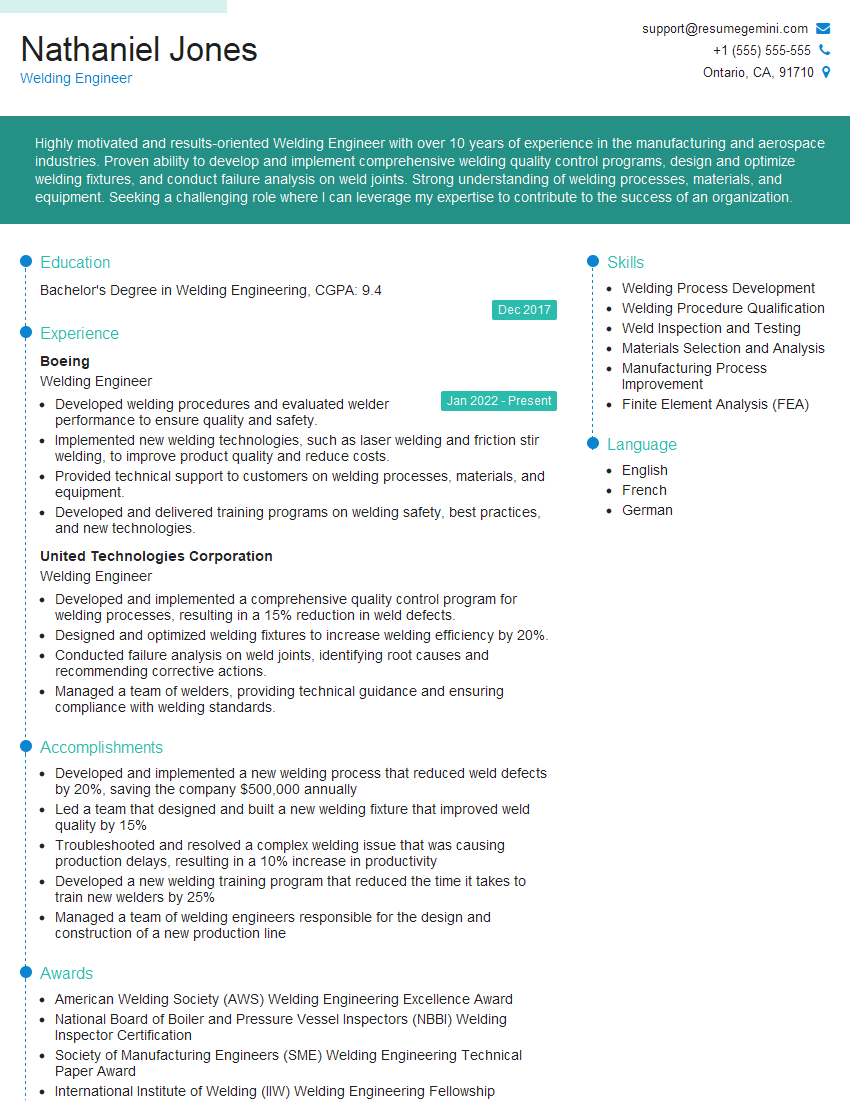

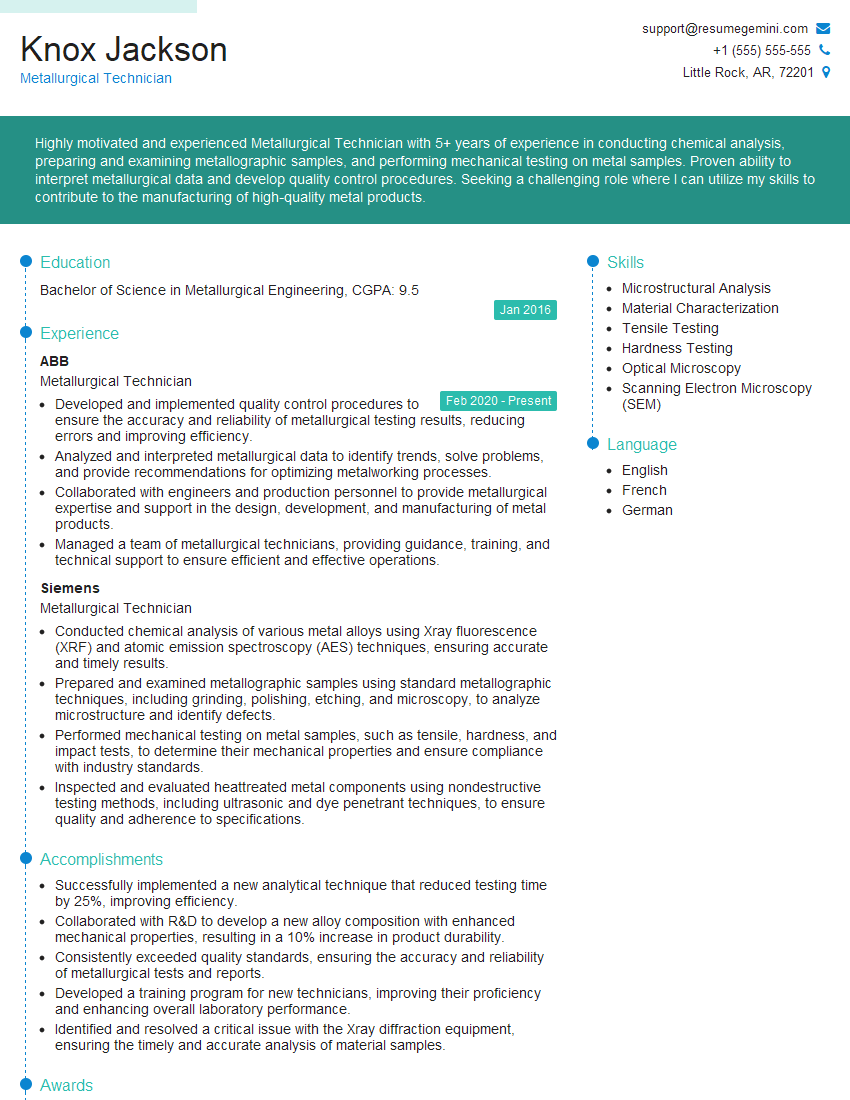

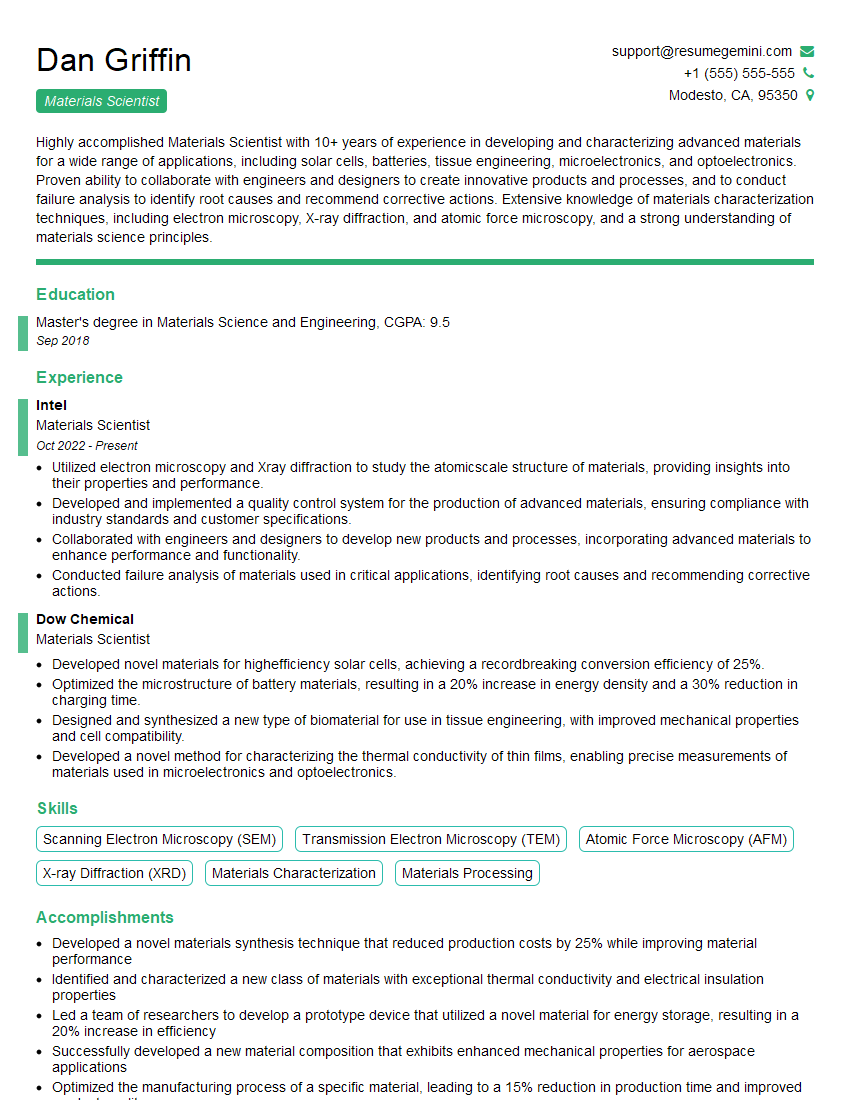

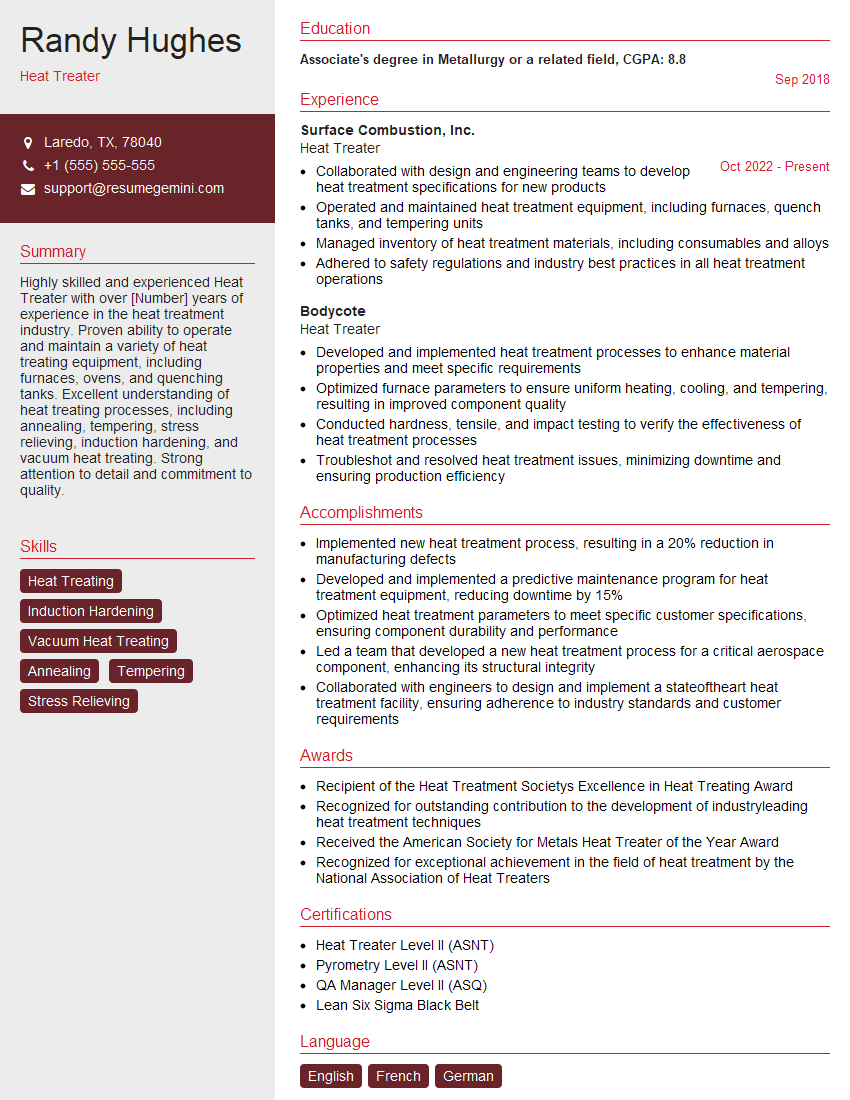

A strong understanding of Metallurgy and Heat Treatment is crucial for career advancement in many engineering fields. It demonstrates a deep technical knowledge and problem-solving ability highly valued by employers. To maximize your chances of landing your dream job, invest time in crafting a compelling, ATS-friendly resume that highlights your skills and experience effectively.

ResumeGemini can help you build a professional resume that stands out from the competition. They provide expert guidance and resources, including examples of resumes tailored to the Metallurgy and Heat Treatment field. Use their tools to showcase your expertise and make a lasting impression on potential employers.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO