Preparation is the key to success in any interview. In this post, we’ll explore crucial Proficient in Optical Software interview questions and equip you with strategies to craft impactful answers. Whether you’re a beginner or a pro, these tips will elevate your preparation.

Questions Asked in Proficient in Optical Software Interview

Q 1. Explain the concept of ray tracing in optical design software.

Ray tracing is a fundamental technique in optical design software that simulates the path of light rays as they propagate through an optical system. Imagine shining a flashlight—ray tracing is like meticulously tracking each individual light ray from the source, through lenses, mirrors, and other optical components, to the final image plane. This allows us to predict how the system will perform before it’s even built.

The software utilizes geometric optics principles, treating light as straight lines (rays). Each ray’s interaction with optical surfaces is calculated using Snell’s law (refraction) and the law of reflection. The software iteratively traces thousands or millions of rays, typically from a source or object point, to determine the intensity and position of the light at the image plane. This process provides crucial data like spot diagrams, ray fan plots, and Modulation Transfer Functions (MTFs), offering a detailed performance assessment.

For example, in designing a telescope, we might ray trace to see how well the system focuses starlight onto a sensor, identifying potential aberrations that need correction.

Q 2. Describe different types of optical aberrations and how to correct them.

Optical aberrations are imperfections in an optical system that cause the image to be blurred or distorted. They arise from the limitations of approximating light propagation using simple geometric optics. Several common types exist:

- Spherical Aberration: Rays passing through different zones of a spherical lens don’t converge at a single point.

- Chromatic Aberration: Different wavelengths of light are refracted differently, leading to color fringes.

- Coma: Off-axis points appear as comet-shaped blur.

- Astigmatism: Off-axis points are blurred into two lines at different locations.

- Distortion: The shape of the image is distorted, such as pincushion or barrel distortion.

- Field Curvature: The image plane is curved instead of flat.

Correction involves using a combination of techniques. For example, aspherical lenses can reduce spherical aberration, while achromatic doublets (combining lenses of different materials) minimize chromatic aberration. Sophisticated optical design software allows for iterative optimization, where the software adjusts lens curvatures, thicknesses, and materials to minimize aberration effects. This often involves setting up merit functions that weigh the relative importance of different aberrations.

Q 3. How do you perform tolerance analysis in optical design software?

Tolerance analysis in optical design software assesses the sensitivity of the optical system’s performance to manufacturing imperfections. Real-world components never have perfectly specified dimensions; there’s always some variation. Tolerance analysis helps determine how much variation is acceptable without significantly degrading the image quality.

The process usually involves defining tolerances for parameters like lens radii, thicknesses, surface irregularities, and material properties. The software then performs Monte Carlo simulations, randomly varying these parameters within the defined tolerances. For each simulation, it ray traces the system and evaluates its performance metrics (e.g., RMS spot size, MTF). This generates a statistical distribution of performance values, indicating the robustness of the design.

This helps identify critical tolerances – parameters where small variations have a large impact on performance. By tightening critical tolerances and relaxing less-sensitive ones, we can optimize manufacturability while maintaining performance.

Q 4. What are the key differences between sequential and non-sequential ray tracing?

Sequential and non-sequential ray tracing are two fundamentally different approaches to simulating light propagation:

- Sequential ray tracing: Assumes that light rays pass through each optical element in a specific sequence. It’s efficient for relatively simple systems where rays don’t cross or interact in complex ways before reaching the image plane. Think of it like tracing a ball rolling down a straight track; it only interacts with each part of the track once.

- Non-sequential ray tracing: Allows for arbitrary interactions between light rays and optical components. It’s crucial for modeling complex systems involving scattering, diffraction, or multiple reflections. Imagine a ball bouncing randomly in a room—the non-sequential method tracks each bounce. It’s essential for systems with freeform surfaces, complex illumination designs, or diffractive elements.

Sequential ray tracing is faster but less versatile. Non-sequential is more accurate and flexible for complex designs, but significantly more computationally intensive.

Q 5. Explain the importance of diffraction effects in optical systems.

Diffraction is the bending of light waves as they pass through an aperture or around an obstacle. While geometric optics ignores diffraction, it’s crucial in many optical systems, particularly those with high numerical aperture or small features. Diffraction limits the ability of an optical system to resolve fine details and can significantly affect the image quality.

Diffraction causes the Airy disk—a central bright spot surrounded by concentric rings. The size of the Airy disk determines the resolution of the system. The smaller the Airy disk, the better the resolution. Diffraction effects must be considered when designing high-resolution imaging systems like microscopes or telescopes. Optical design software often incorporates diffraction calculations to predict the actual performance, which differs from purely geometrical predictions.

For example, in designing a high-resolution camera lens, ignoring diffraction would lead to an overly optimistic prediction of achievable resolution.

Q 6. How do you optimize an optical system for minimum spot size?

Optimizing an optical system for minimum spot size involves minimizing the spread of rays at the image plane. This is achieved through iterative optimization within optical design software. The process typically includes these steps:

- Defining a merit function: This function quantifies the quality of the image, often focusing on the RMS spot radius or similar metrics related to spot size.

- Choosing optimization algorithms: Various algorithms (e.g., damped least squares, simulated annealing) are used to adjust design parameters (lens curvatures, thicknesses, separations, etc.) to minimize the merit function.

- Iterative optimization: The software iteratively adjusts the design parameters, evaluating the merit function at each step. This continues until a satisfactory solution is found or a predefined limit is reached.

- Tolerance analysis: After optimization, a tolerance analysis is performed to ensure that the design remains robust to manufacturing variations.

The specific optimization strategy depends on the complexity of the system and desired performance. Often, constraints are added to the optimization to ensure physical realizability.

Q 7. Describe your experience with various optical materials and their properties.

My experience encompasses a wide range of optical materials, including glasses (e.g., BK7, Fused Silica, various types of flint and crown glasses), crystals (e.g., Calcium Fluoride, Zinc Selenide), and polymers (e.g., PMMA, Zeonex). I’m familiar with their refractive indices, Abbe numbers (a measure of chromatic dispersion), transmission characteristics (dependent on wavelength), thermal expansion coefficients, and mechanical properties. Understanding these properties is critical in selecting appropriate materials for different optical applications.

For instance, Fused Silica is preferred for UV applications due to its high transmission in the UV range, while Zinc Selenide is often chosen for IR applications due to its transparency in the infrared. The choice of material significantly impacts the overall design, influencing aberration correction, thermal stability, and cost. I’ve used this knowledge to optimize designs for specific performance requirements, accounting for factors like material availability and cost.

Q 8. How do you model the performance of a diffractive optical element?

Modeling the performance of a diffractive optical element (DOE) involves rigorously accounting for its diffractive nature, unlike refractive elements modeled solely with Snell’s law. We primarily use scalar diffraction theory for simpler DOEs or rigorous coupled-wave analysis (RCWA) for more complex structures. Scalar diffraction simplifies the problem by assuming the light wave interacts with the DOE’s surface profile but not the bulk material properties. RCWA, on the other hand, considers the interactions within the DOE’s grating structure, providing higher accuracy but requiring significantly more computational resources.

In practice, I’d begin by defining the DOE’s surface profile, typically using a mathematical function or a set of sampled data points. This data then feeds into the chosen model. For scalar diffraction, we’d compute the diffraction efficiency and the resulting wavefront based on the profile’s Fourier transform. RCWA involves solving a system of coupled-wave equations, yielding a more precise prediction of the diffracted orders’ amplitudes and phases. Post-simulation, I analyze the output, focusing on parameters like diffraction efficiency, spot size, uniformity, and wavefront aberrations to assess the DOE’s performance. For example, in designing a DOE for laser beam shaping, I’d look for high diffraction efficiency in the desired order and minimal aberrations to ensure a uniform, well-defined beam profile. The choice between scalar diffraction and RCWA depends on the DOE’s complexity and the required accuracy.

Q 9. Explain the process of creating a tolerancing budget for an optical system.

Creating a tolerancing budget for an optical system is a critical step in ensuring manufacturability and performance. It’s essentially a systematic allocation of allowable errors in various optical components and assembly parameters. The process begins by identifying all the parameters that can affect the system’s performance, such as lens surface radii, thicknesses, center thicknesses, refractive indices, and assembly tolerances. Then, I perform a sensitivity analysis using optical design software (like Zemax or Code V) to determine how each parameter affects the key performance metrics, for example, Modulation Transfer Function (MTF), spot size, or wavefront error.

This sensitivity analysis often uses Monte Carlo simulations. These simulations introduce random variations within each parameter’s tolerance range and assess the resulting performance variations. The goal is to find tolerances that, when combined, maintain acceptable system performance within predefined limits. The budget allocation prioritizes parameters with higher sensitivity. For instance, a lens with a high sensitivity to surface curvature will receive a tighter tolerance than a lens less sensitive to that parameter. The process is iterative, adjusting tolerances until a balanced and achievable budget is obtained. Finally, the budget is documented, specifying the tolerance for each parameter, ensuring consistent manufacturing and assembly processes.

Q 10. Describe your experience with different types of optical coatings.

My experience with optical coatings encompasses a wide range, from simple anti-reflection (AR) coatings to highly specialized multilayer dielectric coatings and metallic coatings. AR coatings are crucial for minimizing unwanted reflections at optical surfaces, increasing transmission and reducing ghost images. I’ve worked extensively with various AR coating designs tailored for different wavelengths and incident angles. Multilayer dielectric coatings provide high reflectance or transmittance at specific wavelengths, finding applications in laser mirrors, dichroic filters, and beamsplitters.

For example, I’ve designed a broadband AR coating for a camera lens, optimizing for visible light, and a narrowband high-reflectance coating for a laser cavity mirror. Metallic coatings, like silver or aluminum, are useful for enhancing reflectance across broad spectral ranges, but they generally exhibit higher absorption and lower damage thresholds compared to dielectric coatings. I’ve used these in applications requiring high reflectance but where the absorption is not a significant concern. In addition, I have experience with coatings designed to handle high power lasers, incorporating specialized materials and design techniques to withstand the intense optical energy and prevent damage.

Q 11. How do you assess the performance of an optical system using MTF analysis?

MTF analysis is a powerful tool for assessing the performance of an optical system by quantifying its ability to transfer spatial frequencies from the object plane to the image plane. A high MTF value indicates good image quality, while a low MTF suggests blurring or other image defects. In practice, I use optical design software to generate the MTF curves for the optical system under different conditions, such as different wavelengths or field angles.

The MTF curves usually show the system’s response as a function of spatial frequency. Analyzing these curves, I can identify the limitations of the system, such as diffraction limits, aberrations (like spherical aberration or coma), or manufacturing errors. For example, a drop-off in MTF at high spatial frequencies indicates a limitation in resolving fine details. Comparing the MTF curves against the system’s specifications, I can determine if the performance meets the design goals. If not, I’d iterate on the optical design, making adjustments to parameters like lens shapes, spacing, or materials to improve the MTF and consequently the image quality. I also use MTF analysis for comparing different design options, guiding the optimization process towards the best overall performance.

Q 12. What are your experiences with Zemax or Code V software?

I have extensive experience with both Zemax and Code V, two leading optical design software packages. My proficiency encompasses all aspects of these programs, including ray tracing, tolerance analysis, optimization, and MTF analysis. In Zemax, I’m comfortable using features such as sequential and non-sequential modellings, optimizing complex systems with many variables, and creating detailed tolerance budgets. I frequently use Zemax’s macro language to automate repetitive tasks and customize the software for specific applications. Similarly, in Code V, I’m adept at using its powerful optimization algorithms, performing detailed aberration analysis, and generating various performance reports. I find both packages valuable, selecting one over the other based on the specific project requirements and personal preference for the user interface and available tools. My expertise extends beyond the basic features, allowing me to efficiently solve complex optical design challenges.

For example, I once used Zemax’s non-sequential modellings to analyze a complex free-space optical communication system, considering scattering and diffraction effects. In another project, I used Code V’s tolerance analysis features to determine the manufacturing tolerances for a high-precision imaging system.

Q 13. Explain your approach to solving complex optical design problems.

My approach to solving complex optical design problems is systematic and iterative. It starts with a clear understanding of the requirements. I begin by thoroughly defining the specifications, including performance metrics, constraints, and environmental factors. Then, I develop a preliminary design based on my experience and knowledge of optical principles. This could involve selecting appropriate lens types, materials, and configurations based on the application requirements (imaging, illumination, etc.).

Next, I use optical design software to model and analyze the system, evaluating its performance against the specifications. This step often requires iterative optimization, where I adjust design parameters to improve performance metrics while satisfying constraints. If I encounter challenging aspects, I might explore different design approaches or utilize advanced optimization algorithms. Throughout this process, I carefully consider manufacturability and cost-effectiveness. Once a satisfactory design is achieved, I perform a comprehensive tolerance analysis to assess its robustness against manufacturing variations. Finally, I document the design, including detailed specifications, analysis results, and manufacturing tolerances.

Q 14. Describe your proficiency in using optical design software for different applications (e.g., imaging, illumination).

My proficiency in using optical design software extends to a variety of applications, including imaging and illumination systems. In imaging systems, I’ve designed lenses for cameras, microscopes, and telescopes, focusing on achieving high resolution, minimizing aberrations, and optimizing for specific wavelength ranges. I utilize the software’s capabilities for optimizing MTF, minimizing distortion, and controlling field curvature. Specific examples include designing a high-resolution camera lens for a medical imaging application and optimizing a telescope objective for enhanced contrast and resolution.

In illumination systems, I’ve utilized the software for designing LED and laser-based lighting systems. This involves modeling light propagation, optimizing light distribution, and achieving uniform illumination over a target area. I’ve applied the non-sequential modellings in software like Zemax to analyze complex illumination scenarios with reflections and scattering. Specific examples include the design of a uniform illumination system for a projection display and optimizing the light distribution for a head-mounted display. My experience encompasses various simulation techniques and optimization algorithms, allowing me to adapt to diverse optical design challenges within both imaging and illumination domains.

Q 15. How do you validate your optical designs through experimentation and testing?

Validating optical designs requires a robust approach combining theoretical modeling with rigorous experimental verification. Initially, simulations using software like Zemax or Code V provide a predicted performance. However, the real world introduces imperfections not captured in simulations. Therefore, building and testing a prototype is crucial.

My process typically involves:

- Prototyping: Constructing a physical representation of the design, paying close attention to component tolerances and assembly procedures.

- Measurement: Employing precise optical instruments such as interferometers (for wavefront analysis), spectrophotometers (for spectral transmission), and MTF (modulation transfer function) measurement systems to quantitatively assess the performance. For example, an interferometer would measure the wavefront errors to assess the accuracy of the design and fabrication.

- Comparison: Carefully comparing the measured data to the simulated predictions. Discrepancies highlight areas needing refinement in either the design or manufacturing process. Root-cause analysis is critical here, perhaps involving finite element analysis (FEA) to understand stress effects on components.

- Iteration: The results inform iterative improvements to the design and manufacturing process. This cycle repeats until the measured performance meets the specified requirements.

For example, in a recent project designing a high-precision imaging system, initial simulations showed excellent performance. However, experimental testing revealed unexpected aberrations due to manufacturing tolerances in lens curvature. By analyzing the discrepancies and refining the design with tighter tolerances, we ultimately achieved the desired image quality.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. What are the limitations of using ray tracing software?

Ray tracing, while a powerful tool, has inherent limitations. It’s a geometric approximation of light propagation, assuming light travels in straight lines (rays) and neglecting diffraction and interference effects. This simplification works well for many applications, but it breaks down in situations where these wave phenomena become significant.

- Diffraction Effects: Ray tracing cannot accurately predict the diffraction patterns produced by apertures, gratings, or other structures smaller than the wavelength of light. This is crucial for high-resolution systems.

- Interference Effects: Interference, essential in phenomena like thin-film interference and anti-reflection coatings, is not directly modeled. While some software incorporates approximate models, they aren’t as accurate as full-wave simulations.

- Computational Cost for Complex Systems: Ray tracing can be computationally intensive for extremely complex systems with many optical elements, limiting the analysis speed and potentially restricting the number of rays traced, leading to statistical noise in the results.

Think of it like drawing a map: Ray tracing is like drawing straight lines between cities – good for general understanding, but it won’t capture the details of the terrain or the experience of driving along the roads.

Q 17. How familiar are you with the concepts of Gaussian optics?

I’m very familiar with Gaussian optics. It provides a simplified yet powerful model for describing optical systems using paraxial approximations (rays close to the optical axis). It’s fundamental for understanding the basic properties of lenses, mirrors, and optical systems.

Key concepts include:

- Focal Length: The distance between the lens and its focal point.

- Focal Power: The reciprocal of the focal length (1/f).

- Thin Lens Equation: (1/object distance) + (1/image distance) = (1/focal length), a simple yet powerful tool for calculating image positions.

- Magnification: The ratio of the image size to the object size.

- Principal Planes and Points: Simplified reference points for tracing rays through a complex lens system.

Gaussian optics forms the basis for many initial optical design steps, providing a quick and efficient way to estimate system performance before moving on to more rigorous ray tracing or wave optics simulations. It’s especially useful in initial design stages to quickly evaluate system parameters and guide the design process. For example, the thin lens equation is used to determine the approximate lens spacing required to achieve the desired image size and location.

Q 18. Describe your experience with polarization effects in optical systems.

Polarization effects are crucial in many optical systems, and I have significant experience incorporating them into designs. Polarization refers to the orientation of the electric field vector of light. Ignoring polarization can lead to significant performance degradation in applications sensitive to polarization states, such as those involving liquid crystals, polarizing beam splitters, or birefringent materials.

My experience includes:

- Modeling Polarization in Software: Utilizing the polarization ray tracing capabilities in optical design software (like Zemax) to analyze the impact of polarization on system performance, including analyzing polarization dependent loss (PDL).

- Polarization Component Selection: Choosing and integrating polarization-sensitive components, such as polarizers, waveplates, and polarization beam splitters, into optical designs to achieve desired polarization control.

- Compensation for Polarization Effects: Designing compensation mechanisms to mitigate undesired polarization effects such as depolarization or polarization-dependent losses.

- Analyzing Polarization-Related Artifacts: Identifying and addressing issues related to polarization-dependent aberrations and ghost images. For instance, I worked on a project where polarized light reflected from different surfaces in a complex optical system interfered destructively in a particular way, impacting the contrast of the final image.

A recent example involved designing a fiber optic sensor system. Careful consideration of polarization effects in the fiber and the optical components was crucial to achieving the desired sensitivity and minimizing signal noise.

Q 19. How do you handle chromatic aberration in optical designs?

Chromatic aberration arises from the refractive index of optical materials being wavelength dependent. This means different wavelengths of light are focused at different points, causing blurred or colored images. Handling chromatic aberration is critical for achieving high-quality imaging.

My approach involves:

- Achromatic Doublets/Triplets: Using combinations of lenses made from different glasses with differing dispersive properties to minimize chromatic aberration. This is a classical solution.

- Diffractive Optical Elements (DOEs): Incorporating DOEs, which use diffraction to control wavelength-dependent focusing, to compensate for chromatic effects. This provides a more compact solution than traditional lens combinations in some cases.

For instance, in designing a spectroscopic instrument, minimizing chromatic aberration was essential for accurate wavelength separation and resolution. By employing an achromatic doublet, we achieved the necessary level of color correction across the spectral range.

Q 20. How do you use optical design software to analyze the impact of manufacturing tolerances on system performance?

Optical design software enables a thorough analysis of manufacturing tolerances and their effect on system performance. Manufacturing imperfections always exist; understanding their impact is vital.

My process uses the following:

- Tolerance Analysis Tools: Utilizing built-in tolerance analysis tools within software like Zemax or Code V. These tools allow for defining tolerances on various parameters (e.g., lens curvature, thickness, center thickness, refractive index) and then running Monte Carlo simulations to assess the impact on image quality and other performance metrics.

- Defining Tolerance Budgets: Establishing allowable tolerances for individual components, balancing performance requirements with manufacturing feasibility and cost. This usually involves trade-off analysis.

- Root-Cause Analysis: When tolerance analysis reveals unacceptable performance degradation, using the software to identify the root cause of the problem, and making adjustments to the design or manufacturing process to mitigate the effect.

For example, in a recent project involving a high-precision laser scanner, tolerance analysis highlighted that small deviations in lens curvature had the greatest impact on the accuracy of the scan. This led to us focusing on tighter tolerances and better manufacturing control for those specific lenses, ensuring accurate system performance despite potential manufacturing imperfections.

Q 21. Describe your experience with free-space optical communication systems.

I have experience designing and analyzing free-space optical communication (FSO) systems. These systems use light beams to transmit data through the atmosphere, offering high bandwidth but susceptibility to atmospheric effects.

My experience encompasses:

- Atmospheric Turbulence Modeling: Incorporating models of atmospheric turbulence (e.g., Kolmogorov turbulence model) into simulations to evaluate the impact of atmospheric conditions on beam propagation and signal quality. This often involved considering beam wander and scintillation.

- Beam Shaping and Control: Designing and analyzing beam shaping techniques to improve the robustness of FSO links against atmospheric turbulence. This often includes Gaussian beam shaping or employing adaptive optics techniques.

- Link Budget Analysis: Performing detailed link budget analysis to determine the achievable data rates and distances, considering factors like transmitter power, receiver sensitivity, atmospheric attenuation, and background noise.

- System Optimization: Optimizing FSO system parameters, such as transmitter aperture size, receiver field of view, and modulation scheme, to maximize performance and reliability.

In a recent project, I worked on a system designed to overcome atmospheric turbulence by employing a laser beam with a specific profile, along with adaptive optics correction in the receiver to compensate for atmospheric distortions. This resulted in a significant improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio and link reliability compared to a system without these compensation strategies.

Q 22. Explain your understanding of different optical system configurations (e.g., Keplerian, Galilean).

Telescope designs fundamentally differ in how they arrange their lenses or mirrors to achieve magnification. Keplerian and Galilean telescopes represent two classic configurations.

Keplerian Telescope: This design uses two convex lenses. The objective lens (larger, closer to the object) forms a real, inverted image. This image then acts as the object for the eyepiece lens (smaller), which further magnifies the image, producing a final magnified, inverted image. Think of the classic refracting astronomical telescope; this is the common type you’d see at a planetarium. It provides a wider field of view but has a longer length compared to a Galilean telescope.

Galilean Telescope: This employs a convex objective lens and a concave eyepiece lens. The concave lens intercepts the light rays before they converge to form a real image. Instead, it diverges the rays to produce a magnified, upright virtual image. Opera glasses and simple spotting scopes often utilize this configuration. They are compact but usually have a narrower field of view and suffer from distortions at the edges.

The choice between these designs depends on factors like the desired magnification, field of view, length, and image orientation. For astronomical observations, the inverted image in a Keplerian telescope is often acceptable, while for terrestrial viewing, the upright image of a Galilean telescope is preferred.

Q 23. How do you optimize optical systems for different spectral ranges?

Optimizing optical systems across different spectral ranges requires careful consideration of material properties and design choices. Different materials have varying refractive indices and absorption characteristics depending on wavelength.

Material Selection: For the visible spectrum (roughly 400-700 nm), common glasses like BK7 and fused silica work well. However, for infrared (IR) applications (e.g., thermal imaging), materials like germanium or zinc selenide are crucial because they are transparent in the IR region while absorbing strongly in the visible range. For ultraviolet (UV) applications, fused silica or calcium fluoride may be necessary. The choice is dictated by the desired transmission window and the system’s performance requirements.

Anti-Reflection Coatings: Anti-reflection (AR) coatings are crucial for minimizing losses due to reflections at lens surfaces. The design of these coatings is wavelength-dependent. Broadband AR coatings are designed to work effectively across a wider spectral range, while narrowband coatings are optimized for a specific wavelength range. The challenge here is to find the balance between broad-band and narrow-band coatings based on the needs of the system.

Diffraction Gratings/Filters: For applications requiring specific wavelength selection, diffraction gratings or optical filters are incorporated. These elements separate or select specific wavelengths, allowing for spectral filtering or dispersion analysis.

Software simulations play a critical role in this optimization process. I utilize optical design software to model the system’s performance across the desired spectral range and iteratively adjust design parameters (e.g., lens curvatures, thicknesses, materials, coatings) to achieve the optimal performance. This involves optimizing for factors like transmission, chromatic aberration (different wavelengths focusing at different points), and image quality.

Q 24. Describe your experience with optical fiber design and modeling.

My experience with optical fiber design and modeling encompasses various aspects, from single-mode to multi-mode fibers. I’ve worked extensively with software packages like COMSOL and Lumerical to simulate and optimize fiber designs.

Single-Mode Fiber Modeling: This involves simulating the propagation of light within the fiber core using techniques like the Finite Element Method (FEM) or Beam Propagation Method (BPM). Optimization targets include minimizing propagation loss, maximizing modal confinement, and controlling dispersion characteristics.

Multi-Mode Fiber Modeling: Simulations here focus on characterizing modal dispersion and power distribution within the fiber. Optimization involves improving modal coupling and reducing intermodal interference for improved data transmission rates.

Fiber Fabrication Parameter Optimization: My work extends to understanding the relationship between fiber fabrication parameters (e.g., preform geometry, drawing temperature, dopant concentration) and fiber characteristics. I’ve used simulations to predict fiber properties based on fabrication parameters and optimize the process for better performance.

For example, I worked on a project designing a novel photonic crystal fiber for highly efficient nonlinear processes. This involved extensive simulations to optimize the fiber’s geometric structure to enhance light confinement and achieve the required nonlinear interactions. This project involved rigorous simulations, comparing theoretical results to experimental data for validation and calibration.

Q 25. How do you utilize paraxial ray tracing in your optical design process?

Paraxial ray tracing is a simplified method for tracing rays through an optical system under the assumption that all rays make small angles with the optical axis. While an approximation, it’s an incredibly valuable tool in the early stages of optical design due to its computational efficiency.

Initial System Design: Paraxial ray tracing is used to quickly estimate the system’s first-order properties such as focal length, magnification, and field of view. It helps to determine the initial lens curvatures and separations needed to meet the basic system requirements.

Aberration Analysis (Preliminary): While it can’t predict all aberrations (imperfections in the image), it provides a preliminary assessment of chromatic and spherical aberrations. This helps identify potential design flaws early on.

Optimization Starting Point: The results of paraxial ray tracing serve as a good starting point for more advanced, non-paraxial ray tracing techniques that consider higher-order aberrations. This reduces the computation time needed for a full, non-paraxial analysis, which is more demanding computationally.

Think of it as a rough sketch of the optical system before you delve into the intricate details. While not fully accurate, it provides valuable insights and significantly speeds up the initial design process. It’s a crucial step that helps eliminate obviously poor designs before investing time in more computationally-intensive non-paraxial analysis.

Q 26. Explain your experience with non-imaging optics and their applications.

Non-imaging optics focus on maximizing the light transfer efficiency between a source and a target, regardless of image quality. Unlike imaging optics, they don’t form sharp images but aim for efficient light concentration or uniform illumination.

Concentrators: Solar concentrators, for instance, use non-imaging optics to focus sunlight onto a smaller area, increasing the intensity for solar thermal or photovoltaic applications. Designs like compound parabolic concentrators (CPCs) are classic examples, designed to accept light from a wide acceptance angle.

Illumination Systems: Non-imaging optics are widely used in LED lighting systems to create uniform illumination over a target surface. Designs like freeform reflectors and lenses are often employed to shape the light distribution efficiently. For example, they’re commonly used in automotive headlights to optimize light distribution and improve visibility.

Light Pipes and Fiber Optics (broadly speaking): While not always categorized explicitly as ‘non-imaging’, the fundamental principle of efficient light transport regardless of image formation aligns with the non-imaging optics philosophy.

My experience includes designing a non-imaging concentrator for a solar thermal application. This involved using specialized software to optimize the reflector shape to maximize the concentration ratio while maintaining a high acceptance angle. The project also involved detailed simulations to predict the system’s efficiency and thermal performance under different environmental conditions.

Q 27. Describe your approach to troubleshooting optical system performance issues.

Troubleshooting optical system performance issues is a systematic process. It typically begins with a thorough understanding of the system’s specifications and expected performance. I follow a multi-step approach:

Analyze Measured Data: Start with the data – measured performance parameters like MTF (modulation transfer function), spot diagrams, and wavefront aberrations. Comparing these results with the design specifications highlights areas needing attention.

Identify Potential Sources of Error: This could involve examining lens alignment, manufacturing tolerances, coating defects, environmental factors (temperature, vibrations), or even issues with the measurement setup itself.

Software Simulation and Modeling: Utilize optical design software to simulate the system’s performance under various conditions, incorporating the measured deviations from the ideal design. This helps pinpoint likely culprits.

Iterative Refinement and Testing: Based on the simulation results and identified issues, I make iterative refinements to the system’s design or physical setup. Each modification is then followed by testing and further analysis until the performance meets the specifications.

Root Cause Analysis: It is crucial to identify the root cause. Was there a problem with the original design, manufacturing, or the operational environment? Addressing the root cause prevents recurrence.

For example, in one project, a low MTF was traced to a slight misalignment of a lens element. Simulation revealed this misalignment significantly impacted image quality. Once the alignment was corrected, the MTF improved considerably.

Key Topics to Learn for Proficient in Optical Software Interview

- Fundamentals of Optics: Understanding basic optical principles like refraction, reflection, diffraction, and polarization is crucial. Prepare to discuss how these concepts apply within the software.

- Optical System Design: Familiarize yourself with the process of designing optical systems using software. This includes understanding lens design, tolerancing, and optimization techniques.

- Software-Specific Features: Deeply understand the specific software you’re being interviewed for. Focus on its unique capabilities, workflow, and common applications.

- Image Processing and Analysis: Many optical software packages involve image processing. Practice working with image data, performing analysis, and interpreting results.

- Simulation and Modeling: Master the software’s simulation tools. Be prepared to discuss the creation and interpretation of simulations, including ray tracing and other relevant techniques.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Optical software often generates large datasets. Develop your ability to analyze this data, draw conclusions, and present your findings effectively.

- Troubleshooting and Problem-Solving: Be prepared to discuss your approach to troubleshooting common issues encountered when using the software. Highlight your problem-solving skills and analytical abilities.

- Specific Applications: Consider the industry you’re targeting (e.g., medical imaging, astronomy, lithography). Familiarize yourself with how the software is used in those specific applications.

Next Steps

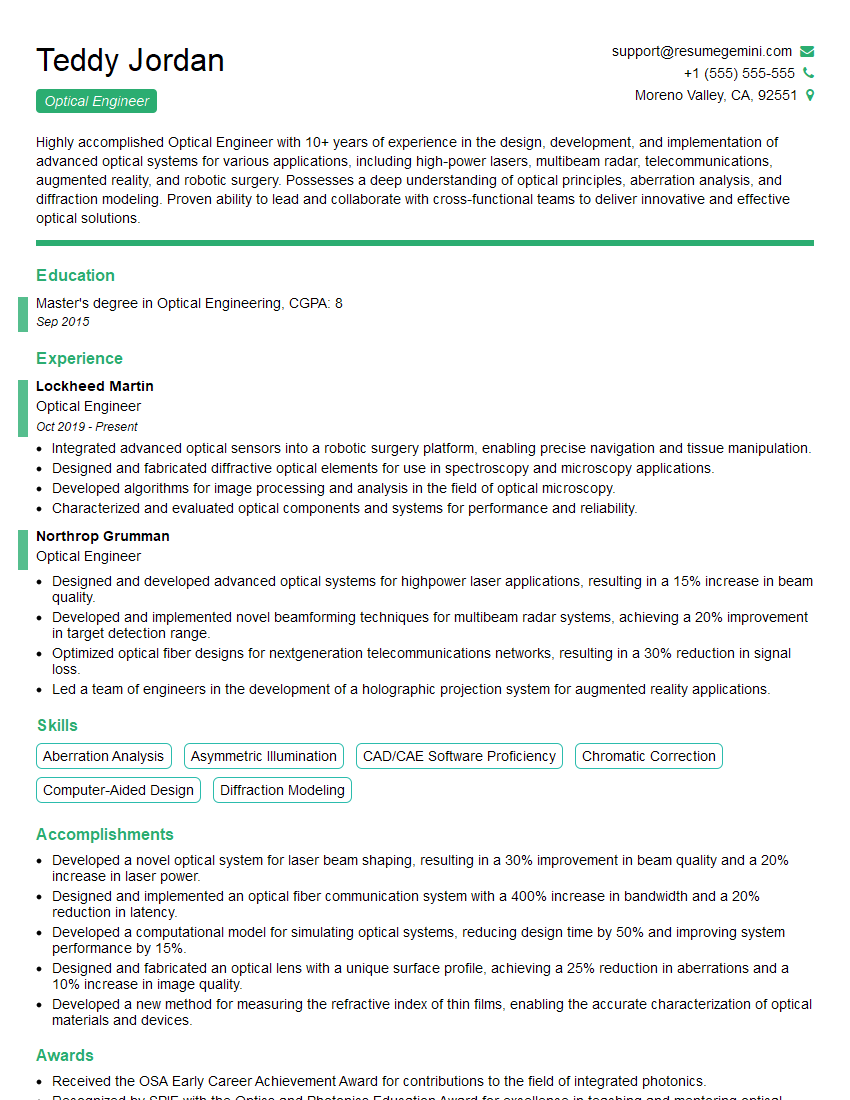

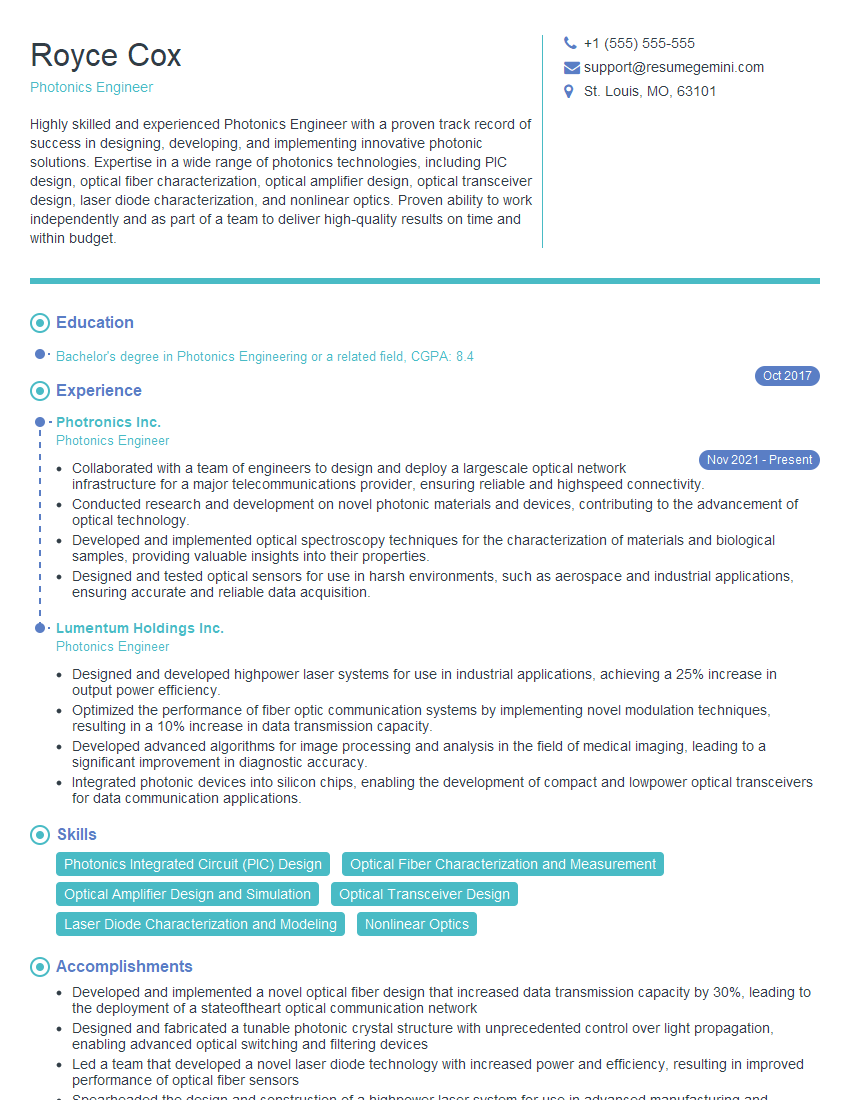

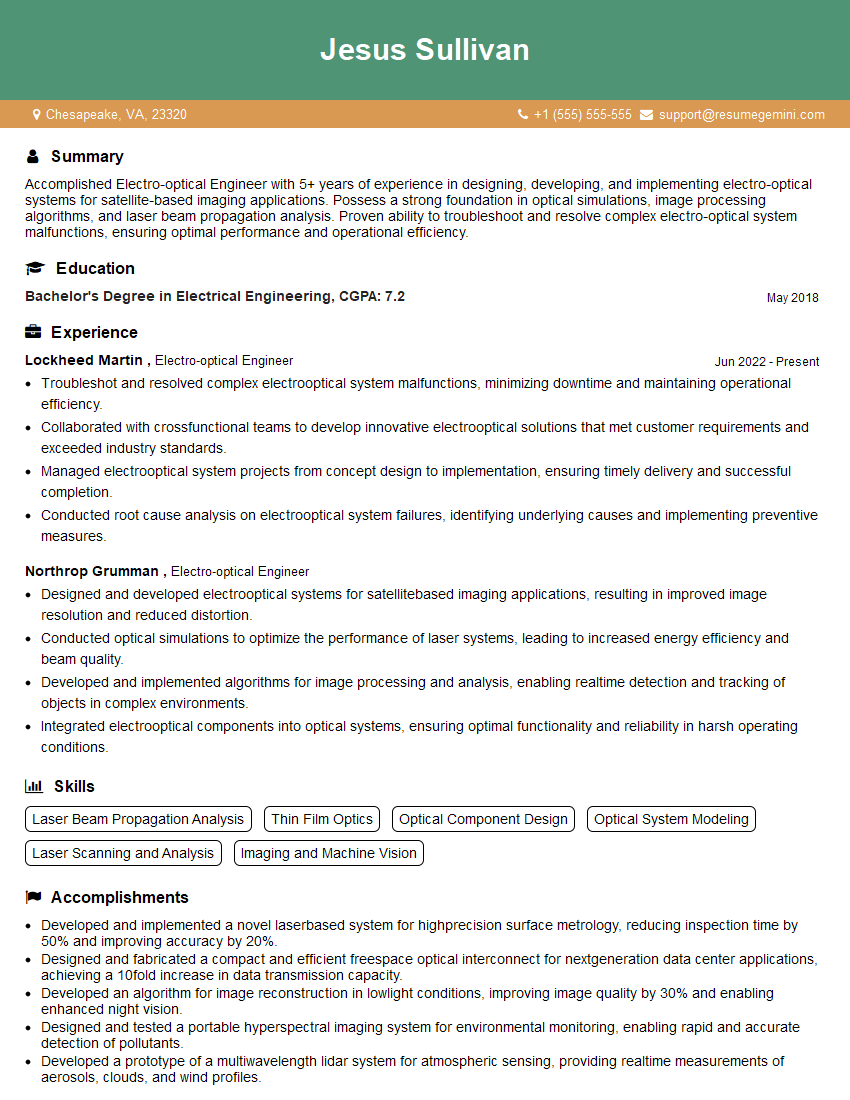

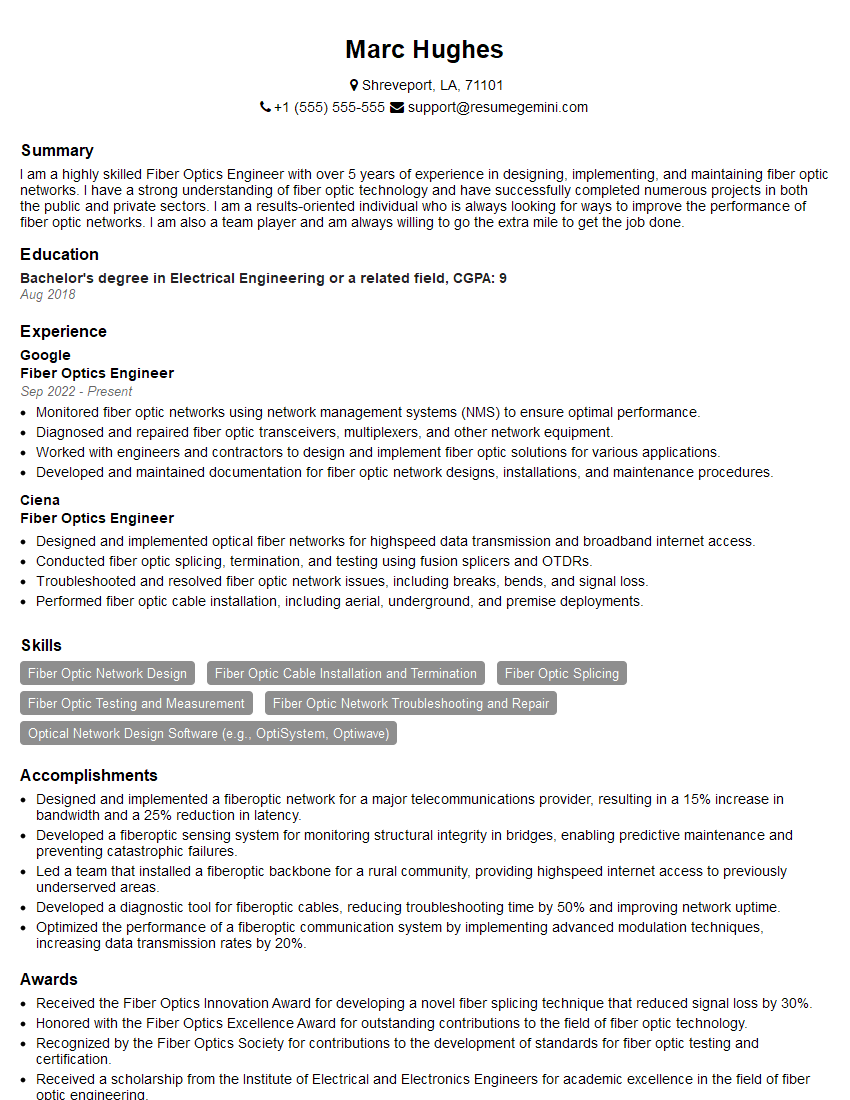

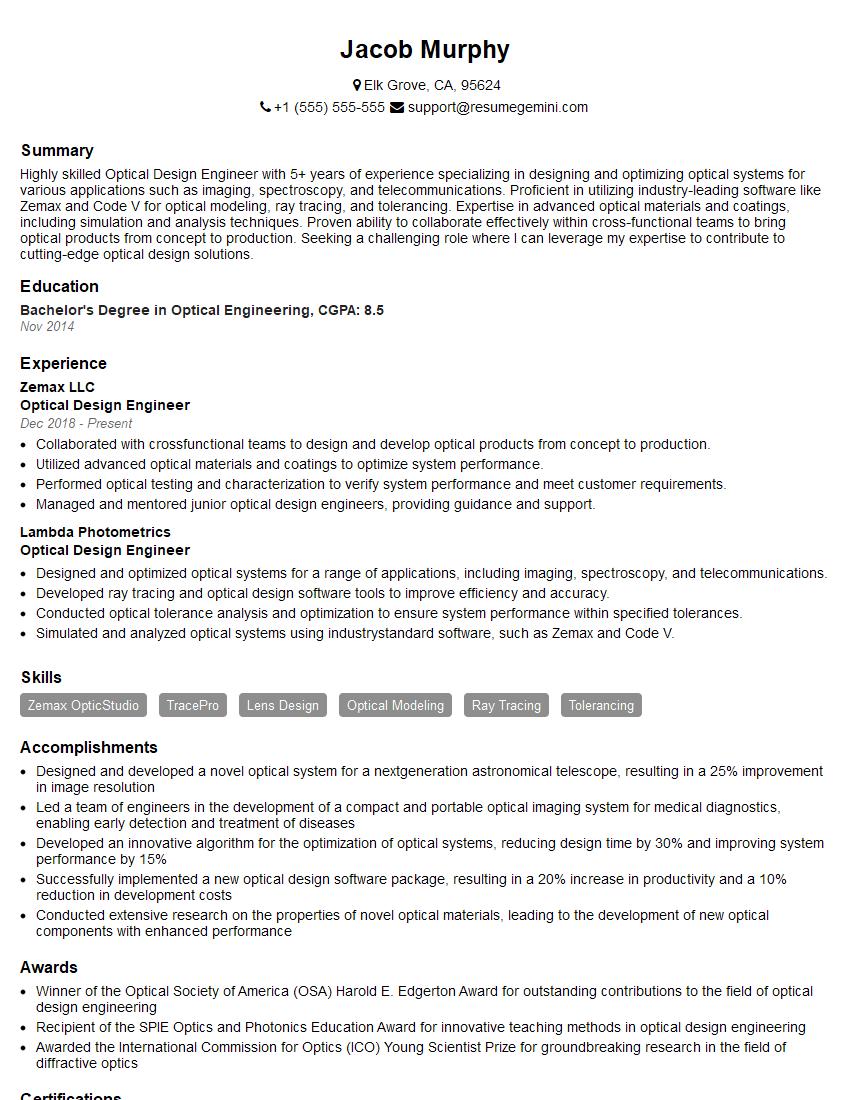

Mastering Proficient in Optical Software opens doors to exciting career opportunities in cutting-edge fields. To maximize your chances, create an ATS-friendly resume that highlights your skills and experience effectively. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource to help you build a professional and impactful resume. They provide examples of resumes tailored to Proficient in Optical Software to guide you. Invest the time in crafting a strong resume; it’s your first impression and a critical step in landing your dream job.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO