The thought of an interview can be nerve-wracking, but the right preparation can make all the difference. Explore this comprehensive guide to Use of Measuring Tools interview questions and gain the confidence you need to showcase your abilities and secure the role.

Questions Asked in Use of Measuring Tools Interview

Q 1. What are the different types of calipers and their applications?

Calipers are precision instruments used for measuring the dimensions of objects. Several types exist, each suited to specific tasks.

- Vernier Calipers: These are the most common type, using a main scale and a vernier scale to achieve high precision (typically 0.01mm or 0.001 inches). They are versatile and used for measuring internal and external diameters, depths, and step heights. Imagine needing to precisely measure the diameter of a small bearing – vernier calipers are perfect for this.

- Digital Calipers: Similar in functionality to vernier calipers, digital calipers display the measurement directly on an LCD screen, eliminating the need for manual interpretation of scales. They offer quick measurements and easy data recording. For example, in a manufacturing setting, a digital caliper might be preferred for high-throughput quality control checks.

- Dial Calipers: These calipers use a rotating dial to display measurements. Though less common than vernier or digital calipers, they are robust and reliable. One practical application is in mechanical workshops where a quick, visual read-out is important.

- Inside/Outside Calipers: These are simpler calipers designed for measuring internal and external dimensions respectively. They don’t provide precise numerical readings but are useful for quick, approximate measurements, such as transferring dimensions from a drawing to a workpiece.

The choice of caliper depends heavily on the required accuracy, ease of use, and the nature of the measurement being taken.

Q 2. Explain the principle of operation of a micrometer.

A micrometer, or micrometer caliper, operates on the principle of precise screw threads. A precisely machined screw is rotated within a fixed frame. Each complete rotation of the screw moves a thimble a precise distance (usually 0.5mm or 0.025 inches). A smaller scale on the thimble allows for finer measurements down to 0.01mm or 0.001 inches. The measured object is placed between the anvil (fixed part) and the spindle (movable part). The screw is then turned until the object is lightly held. The combined reading from the main scale and the thimble scale gives the precise dimension. It’s like measuring with a very fine, calibrated screw, giving incredible accuracy.

Q 3. How do you determine the accuracy of a measuring instrument?

Determining the accuracy of a measuring instrument involves comparing its readings to a known standard. This standard is usually another instrument of higher accuracy (a traceable standard). The process often involves:

- Calibration: Comparing the instrument’s readings to a certified standard across its entire measurement range.

- Uncertainty Analysis: Identifying all potential sources of error (e.g., instrument resolution, environmental factors, operator error) and quantifying their impact on the measurement result. This will provide an overall uncertainty budget.

- Traceability: Ensuring that the calibration standard used itself can be traced back to national or international standards.

For example, a digital caliper might be calibrated using a calibrated gauge block set. The difference between the caliper’s readings and the known dimensions of the gauge blocks indicates the accuracy and any systematic errors. A calibration certificate will document the results.

Q 4. What is the difference between precision and accuracy in measurement?

Precision and accuracy are distinct concepts in measurement, though often confused. Imagine you are throwing darts at a dartboard:

- Accuracy refers to how close the measurement is to the true value. Accurate darts would cluster around the bullseye.

- Precision refers to the repeatability of the measurements. Precise darts would be tightly clustered together, regardless of whether they are near the bullseye or not.

High precision doesn’t necessarily imply high accuracy (a tightly clustered group of darts far from the bullseye). Similarly, a measuring instrument can be precise (giving consistent readings) but inaccurate (systematically deviating from the true value). Ideally, a good measuring instrument is both precise and accurate.

Q 5. Describe the process of calibrating a digital caliper.

Calibrating a digital caliper typically involves using a gauge block of known dimension. The process involves:

- Zeroing: Close the jaws of the caliper completely and zero the instrument. Many digital calipers have a dedicated “zero” or “reset” button.

- Calibration Check: Insert a gauge block of a known dimension (e.g., 10mm or 1 inch). Compare the caliper’s reading to the known value. A small discrepancy is acceptable, depending on the instrument’s specifications.

- Adjustment (If Necessary): Some digital calipers offer a calibration adjustment function that allows for minor corrections (consult the instrument’s manual). However, significant deviations often indicate a need for professional calibration.

- Record Keeping: Always record the calibration date, gauge block dimensions, and any noted discrepancies. A calibration sticker is useful.

Note: Professional calibration services use more sophisticated methods and equipment.

Q 6. How would you handle a situation where a measuring tool is malfunctioning?

If a measuring tool malfunctions, the immediate action depends on the nature of the malfunction. First, identify the issue: is it a dead battery (digital tools), damaged jaws, a loose screw, or an erratic display?

- Minor Issues (e.g., dead battery, loose parts): Replace the battery, tighten the screws, or clean the jaws. If the problem persists, move to the next steps.

- Major Issues (e.g., erratic display, significant inaccuracies): Do not use the tool. Tag it as “out of service” and immediately notify your supervisor or the relevant authority. Do not attempt repairs yourself unless you are qualified to do so.

- Calibration Check: Even with minor issues, it’s prudent to check if the tool is still within its calibration limits, as a minor problem might indicate a deeper issue.

- Documentation: Always document the malfunction, the actions taken, and the date. This is crucial for traceability and preventing similar issues.

Using a malfunctioning tool can lead to inaccurate measurements and potentially dangerous outcomes. Prioritizing safety is paramount.

Q 7. What are the common sources of measurement errors?

Measurement errors can stem from various sources:

- Instrument Errors: These include inherent inaccuracies in the instrument’s construction, wear and tear, or improper calibration.

- Environmental Errors: Temperature changes, humidity, and vibrations can influence measurements.

- Operator Errors: Incorrect reading of scales, parallax errors (incorrect viewing angle), improper handling, and poor technique contribute to errors. This is very common!

- Method Errors: Inaccurate clamping pressure on the workpiece, using an unsuitable tool for the task, and improper setup all introduce errors.

- Workpiece Errors: Defects or irregularities in the measured object can also affect the measurements.

Minimizing these errors requires careful planning, the use of appropriate tools, proper technique, and regular calibration and maintenance.

Q 8. Explain how to minimize measurement errors.

Minimizing measurement errors is crucial for accuracy and reliability in any technical field. It involves a multi-pronged approach focusing on the tool, the technique, and the environment.

Calibration and Tool Selection: Always ensure your measuring tools are properly calibrated and appropriate for the task. Using a micrometer to measure a large object is inefficient and prone to error; a tape measure would be far better. Regular calibration against a known standard is paramount.

Proper Technique: This includes understanding the tool’s limitations and operating procedures. For example, when using a caliper, ensure you avoid parallax error by keeping your eye directly above the measurement scale. With a tape measure, ensure it’s taut and flat against the surface being measured.

Environmental Factors: Temperature fluctuations can affect the accuracy of some tools (especially metallic ones). Ensure consistent environmental conditions throughout the measurement process. Vibrations can also introduce error – find a stable surface to perform measurements.

Multiple Measurements: Taking multiple measurements and calculating the average significantly reduces the impact of random errors. This is a standard practice in most engineering disciplines.

Data Recording: Meticulous record-keeping is essential. Note down the tool used, date, time, and environmental conditions along with the measurements. This allows for error analysis later on.

For instance, when measuring the diameter of a shaft, taking three readings at different angles and calculating the average yields a more precise result than a single measurement.

Q 9. What safety precautions should be taken when using measuring tools?

Safety when using measuring tools depends heavily on the specific tool but some general precautions apply across the board:

Eye Protection: Always wear safety glasses, especially when using tools that might chip or break, like dial indicators or hardened steel rulers. Flying debris is a significant hazard.

Proper Handling: Handle tools with care. Don’t drop them or force them beyond their designed limits. For example, avoid applying excessive pressure to a delicate instrument like a dial gauge.

Sharp Objects: Be mindful of sharp points or edges on tools such as calipers or steel rules. Avoid pointing them towards yourself or others.

Electrical Hazards: If using electronic measuring tools, ensure they are properly grounded and used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Never use them in wet environments unless explicitly designed for such use.

Clothing and Jewelry: Loose clothing or jewelry can get caught in moving parts of some measuring devices. Secure loose items before starting work.

Always refer to the manufacturer’s safety guidelines for specific tools. A simple mistake can lead to serious injury.

Q 10. How do you select the appropriate measuring tool for a specific task?

Selecting the right measuring tool hinges on the task’s requirements, specifically the accuracy needed and the size/shape of the object being measured. Here’s a stepwise approach:

Determine the required accuracy: Do you need measurements to the nearest millimeter, micrometer, or something in between? This dictates the precision of the tool required.

Consider the size and shape of the object: A small caliper is unsuitable for measuring the length of a long pipe, while a tape measure might be inaccurate for measuring the diameter of a small pin.

Assess the material’s characteristics: Measuring a rough surface requires a different tool than measuring a smooth, polished one. A surface gauge might be preferable for irregular surfaces.

Choose the appropriate tool: Based on the above factors, select the most suitable tool – a ruler, tape measure, caliper, micrometer, dial indicator, laser distance meter, etc.

For example, measuring the thickness of a sheet of metal would require a micrometer for high accuracy, whereas measuring the length of a room would necessitate a tape measure for speed and convenience.

Q 11. What are the limitations of different measuring tools?

Every measuring tool has limitations. Understanding these limitations is crucial to avoid errors:

Rulers and Tape Measures: Limited accuracy (typically to the nearest millimeter or fraction of an inch), prone to bending or stretching, susceptible to parallax error.

Calipers: Less precise than micrometers, potential for wear and tear affecting accuracy, less suitable for very small or very large objects.

Micrometers: High accuracy but require careful handling, sensitive to temperature variations, can be slow to use for multiple measurements.

Dial Indicators: Highly sensitive to minute changes but susceptible to external vibrations, requires careful zeroing, not suitable for large-scale measurements.

Laser Distance Meters: Affected by atmospheric conditions and reflective surfaces, may struggle with rough surfaces.

For instance, while a micrometer offers high accuracy, it is less suitable for measuring the overall length of a complex part.

Q 12. Explain the concept of tolerance in engineering drawings.

Tolerance in engineering drawings specifies the permissible variation in the dimensions of a component. It defines an acceptable range of values around a nominal (target) size. This range accounts for manufacturing limitations and allows for slight variations without compromising functionality.

Tolerance is often expressed as a plus/minus value (e.g., 10 ± 0.1 mm) indicating that the actual dimension can fall between 9.9 mm and 10.1 mm. It can also be specified using limits (e.g., 10+0.1-0.2 mm) showing upper and lower bounds.

Understanding tolerance is critical. A part made outside of the specified tolerance might be unusable, leading to costly rework or failure.

For example, a shaft designed with a diameter tolerance of 25 ± 0.05 mm must have a diameter between 24.95 mm and 25.05 mm to be considered acceptable.

Q 13. How do you interpret measurement readings from different types of tools?

Interpreting measurement readings requires careful attention to the tool’s scale and units. Each tool has its own specific way of displaying measurements.

Rulers and Tape Measures: Readings are straightforward, aligning the mark with the scale to obtain the measurement. Units are usually millimeters or inches.

Calipers: Readings usually involve two scales (main and vernier). Understanding how to read both scales is essential for accurate measurements.

Micrometers: These typically have a thimble and barrel scale. The measurement is derived by combining readings from both scales. They are usually in millimeters or inches.

Dial Indicators: These show readings directly on a dial. The unit of measurement and scale are indicated on the gauge face. Always check the zero setting before measurements.

Understanding the units (metric or imperial) and the smallest division on the scale are crucial for accurate reading. It’s vital to be methodical and double-check your readings, especially for critical measurements.

Q 14. Describe your experience using dial indicators.

I have extensive experience using dial indicators, particularly in precision machining and quality control applications. I’ve used them for a variety of tasks, including:

Measuring runout: Assessing the concentricity of rotating parts like shafts or bearings.

Checking flatness: Evaluating the surface flatness of machined components using a surface plate.

Measuring parallelism: Determining the parallelism between two surfaces.

Monitoring dimensional changes during machining: Tracking dimensional changes during milling or turning operations to ensure accuracy.

I’m proficient in zeroing the indicator, selecting appropriate ranges, and interpreting the readings accurately. I am also familiar with various types of dial indicators, including contact point and magnetic bases. Experience has taught me the importance of minimizing external vibrations and ensuring the indicator is firmly mounted for accurate and reliable results.

In one instance, I used a dial indicator to detect a subtle runout in a precision shaft, preventing a costly assembly failure. This highlighted the crucial role of careful measurements using appropriate tools.

Q 15. How do you use a vernier scale?

A vernier scale is a precision instrument used to measure lengths with greater accuracy than a standard ruler. It works by employing two scales: a main scale and a vernier scale. The vernier scale slides along the main scale, allowing for precise readings.

How to Use It:

- Align the scales: Place the object to be measured against the jaws of the vernier caliper. Ensure both scales are aligned at the zero mark.

- Read the main scale: Note the value on the main scale just before the zero mark of the vernier scale. This is the whole number part of your measurement.

- Read the vernier scale: Find the line on the vernier scale that perfectly aligns with a line on the main scale. The number of this line on the vernier scale represents the fractional part of your measurement.

- Combine readings: Add the main scale reading and the vernier scale reading to obtain the total measurement.

Example: If the main scale reading is 2.5 cm and the vernier scale reading is 0.04 cm, the total measurement is 2.54 cm.

Vernier scales are crucial in various fields, from engineering and manufacturing to woodworking and jewelry making, where high precision is needed.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. What are the different types of measuring tapes and their uses?

Measuring tapes come in various types, each suited for specific applications. The choice depends on the task’s precision, material being measured, and environmental conditions.

- Cloth/Fiber Glass Tapes: These are flexible and lightweight, commonly used for measuring lengths around the house or in construction projects. Fiber glass versions are more durable and less prone to stretching.

- Steel Tapes: Designed for accuracy and durability, they are used in surveying, construction, and engineering. Steel tapes offer better precision than cloth tapes and resist stretching.

- Electronic Measuring Wheels: These combine a wheel with a digital counter for measuring longer distances quickly and efficiently. Ideal for large-scale projects, such as land surveying or road construction.

- Tailor’s Tapes: These are usually made of flexible materials with inch and centimeter markings. They are specifically designed for taking body measurements.

Choosing the right type involves considering the required accuracy, the length to be measured, and the material’s properties. For instance, using a steel tape for precise land measurements guarantees accuracy, while a cloth tape suffices for quick home projects.

Q 17. Explain the process of using a level.

A level is a tool used to determine whether a surface is horizontal or vertical. It uses gravity to ensure the instrument shows a true level surface. Different types exist, including spirit levels, laser levels, and digital levels.

Using a Spirit Level:

- Place the level: Position the level on the surface to be checked.

- Observe the bubble: Look at the air bubble within the vial. The bubble should rest in the center of the vial’s markings, indicating that the surface is level.

- Adjust as needed: If the bubble is not centered, adjust the surface until the bubble is in the center. This might involve adding shims or adjusting the height of the surface.

Using a Laser Level: Laser levels project a horizontal or vertical line using a laser beam. They are easy to use and can cover longer distances. Align the laser beam with the desired level. Any deviations indicate that the surface is not level.

Levels are vital in construction, plumbing, and various trades where accurately leveling surfaces is paramount, ensuring structural integrity and functionality.

Q 18. How do you measure angles using a protractor?

A protractor is a semicircular instrument used to measure angles. It typically has markings from 0° to 180°.

Measuring an Angle:

- Place the protractor: Position the protractor’s base line along one arm of the angle, with the protractor’s center point on the angle’s vertex (the point where the two lines meet).

- Align the zero mark: Make sure the zero-degree mark aligns with one arm of the angle.

- Read the measurement: Observe the point where the other arm of the angle intersects the protractor’s scale. This is the angle’s measurement in degrees.

Remember that protractors can measure angles up to 180°. For larger angles, you may need to measure them in parts or use a different tool.

Protractors find use in mathematics, geometry, drafting, construction, and engineering where precise angle measurement is necessary.

Q 19. What are the different units of measurement and their conversions?

Various units measure length, weight, volume, and other quantities. Consistent conversion between them is essential.

Common Units and Conversions:

- Length: Millimeters (mm), centimeters (cm), meters (m), kilometers (km), inches (in), feet (ft), yards (yd), miles (mi).

1 m = 100 cm = 1000 mm; 1 ft = 12 in; 1 yd = 3 ft - Weight/Mass: Grams (g), kilograms (kg), milligrams (mg), ounces (oz), pounds (lb), tons.

1 kg = 1000 g; 1 lb ≈ 454 g - Volume: Milliliters (mL), liters (L), cubic centimeters (cc), cubic meters (m³), gallons (gal), quarts (qt).

1 L = 1000 mL; 1 L ≈ 1.057 qt

Accurate conversion is crucial for consistency and avoiding errors in calculations and engineering designs. Using conversion factors and online converters helps ensure accuracy.

Q 20. How do you record measurements accurately and consistently?

Accurate and consistent measurement recording is fundamental to data reliability. It involves several steps:

- Use the right tool: Select the appropriate measuring instrument for the task, ensuring its calibration is up-to-date.

- Record units: Always specify the units of measurement used (e.g., mm, cm, kg). Avoid ambiguity.

- Use significant figures: Report measurements with the appropriate number of significant figures, reflecting the instrument’s precision.

- Multiple readings: Take multiple readings, especially for critical measurements. This helps average out potential errors.

- Organized recording: Keep a detailed record of measurements, including date, time, instrument used, and any relevant environmental conditions.

- Check for errors: Review recorded measurements to identify potential errors. Recheck measurements if necessary.

Consistent recording practices minimize errors, enhancing data analysis and decision-making across various industries.

Q 21. What is the significance of traceability in measurement?

Traceability in measurement refers to the ability to trace a measurement back to a known standard or reference. This ensures that measurements are consistent and comparable across different instruments, locations, and times. It involves a chain of comparisons that links the measurement to a national or international standard.

Significance:

- Accuracy and Reliability: Traceability enhances the accuracy and reliability of measurements by providing a known reference point.

- Comparability: It ensures that measurements taken at different times or locations can be compared accurately.

- Quality Control: Traceability is crucial for quality control and compliance with industry standards and regulations.

- Legal and Regulatory Compliance: In many industries, traceability is mandated by regulations to guarantee product safety and quality.

Without traceability, measurements lack context and consistency, limiting their value and potentially leading to errors with significant consequences. For example, in pharmaceutical manufacturing, traceability is crucial for ensuring the accuracy of drug dosages.

Q 22. Explain your experience with statistical process control (SPC) in relation to measurements.

Statistical Process Control (SPC) is crucial for ensuring consistent product quality by monitoring and controlling variation in manufacturing processes. In relation to measurements, SPC involves using control charts to track measurement data over time. This allows us to identify trends, patterns, and anomalies that might indicate problems with the measurement process itself or the underlying process producing the parts being measured.

For example, I’ve used control charts like X-bar and R charts to monitor the diameter of machined parts. By plotting the average diameter (X-bar) and the range of diameters (R) from samples taken at regular intervals, we can quickly see if the process is stable and producing parts within acceptable tolerances. Out-of-control points signal potential issues requiring investigation, such as tool wear, machine malfunction, or changes in material properties. This proactive approach prevents the production of non-conforming parts and saves time and resources.

My experience also includes using capability analysis to determine if a process is capable of meeting specified requirements. This involves calculating Cp and Cpk indices, which quantify the process capability relative to the tolerance limits. Low Cp/Cpk values indicate that the process is not capable and requires improvement, whether through process adjustments or improved measurement accuracy.

Q 23. How would you troubleshoot a discrepancy between two measurement readings?

Troubleshooting discrepancies between two measurement readings requires a systematic approach. First, I’d verify the accuracy and calibration of both measuring instruments. Were they recently calibrated? Are they within their specified calibration intervals? A simple recalibration can often resolve the issue.

Next, I’d consider potential sources of error. This could include environmental factors (temperature, humidity), operator error (incorrect measurement technique, misreading the instrument), or inherent variability in the measured object. I might repeat the measurements multiple times using the same instruments and techniques to assess the repeatability of the readings. Significant variations would indicate a potential problem.

If the discrepancy persists, I would investigate the measurement techniques used. Did both operators use the same method? Were the measurements taken at the same location on the object? Was the object properly fixtured? A detailed analysis of the measurement process, including a thorough check of the measurement setup, is critical. Finally, if all other factors are ruled out, it might be necessary to use a more precise or accurate measuring device for verification.

Q 24. Describe your experience with laser measurement tools.

I have extensive experience using laser measurement tools, particularly laser scanners and laser distance meters. Laser scanners provide highly accurate three-dimensional measurements of complex shapes, making them ideal for reverse engineering, quality control, and rapid prototyping. I’ve used them extensively in applications such as scanning automotive parts for dimensional inspection and creating CAD models from physical objects.

Laser distance meters offer quick and precise measurements of distances, often with capabilities to calculate areas and volumes. These are particularly useful for tasks like site surveying, construction, and large-scale dimensional checks. For instance, I’ve used them to measure the dimensions of large structures during construction projects, verifying that they conform to the blueprints.

Beyond specific applications, my experience encompasses understanding the limitations of laser technology, such as the effects of surface reflectivity and environmental conditions on measurement accuracy. I know how to select the appropriate laser tool for a given task based on the required accuracy, range, and the nature of the object being measured.

Q 25. What are some advanced measuring techniques you are familiar with?

Beyond the common measuring techniques, I’m familiar with several advanced methods. These include coordinate measuring machine (CMM) programming and operation, which enables highly precise three-dimensional measurements of complex parts. I’m proficient in developing CMM measurement routines, using different probe types, and analyzing the results to identify deviations from specifications.

I also have experience with optical metrology techniques, such as interferometry, which utilizes the interference of light waves to measure extremely small displacements or surface irregularities. This is crucial for applications requiring nanometer-level precision. Furthermore, I’m acquainted with various image-based measurement techniques used for automated inspection and quality control.

My knowledge extends to structured light scanning, which uses projected light patterns to create 3D models, offering a non-contact method for accurate surface measurements. This technique is useful when dealing with fragile or delicate parts. I am also familiar with analyzing and interpreting measurement results from these various advanced techniques, using statistical tools to understand the data and assess its implications.

Q 26. Explain your understanding of dimensional metrology.

Dimensional metrology is the science of measuring the physical dimensions of objects. It encompasses the theoretical and practical aspects of accurate and precise measurement, including the selection of appropriate instruments, the execution of measurement procedures, and the interpretation of measurement results. This involves understanding different types of errors—systematic, random, and human—that can affect the accuracy of measurements.

My understanding includes proficiency in using various measurement standards and traceability to national or international standards. This ensures the consistency and reliability of measurements across different locations and organizations. It’s essential to ensure that measurements are traceable to a known standard, allowing for comparison and validation of results. I also understand the importance of proper documentation and reporting of measurement results, including uncertainty analysis.

Furthermore, I understand the concepts of tolerance, fit, and form, and how these relate to the design and manufacturing of parts. Accurate dimensional metrology is crucial for ensuring that parts meet their design specifications and function correctly within an assembly. A thorough understanding of dimensional metrology is critical for quality control, process optimization, and ensuring the reliability and safety of products.

Q 27. How do you ensure the proper maintenance of measuring tools?

Proper maintenance of measuring tools is essential for ensuring accurate and reliable measurements. This involves a multi-pronged approach. First, regular calibration is paramount. I follow a strict calibration schedule for all tools, ensuring that they’re calibrated at the recommended intervals by a certified laboratory. Calibration certificates provide documented evidence of the tool’s accuracy and traceability.

Second, I adhere to proper handling and storage procedures. This includes using appropriate storage cases to protect the instruments from damage and environmental factors, such as extreme temperatures or humidity. Careful handling prevents accidental damage or misuse, which could compromise accuracy. For example, delicate instruments like micrometers should be stored in cushioned cases to prevent damage to the measuring surfaces.

Third, I perform routine cleaning and inspection of the measuring tools. This removes any debris or contamination that could interfere with measurements. Regular inspections reveal any signs of wear, damage, or misalignment that might require repair or replacement. This proactive approach helps ensure the continued accuracy and longevity of the tools.

Q 28. Describe a time you had to solve a problem involving inaccurate measurements.

In a previous project involving the manufacturing of precision gears, we encountered inconsistent measurements of gear tooth thickness. Initial measurements using a conventional micrometer showed significant variability, leading to concerns about the quality and performance of the gears. The initial assumption was a problem with the manufacturing process itself.

However, after a thorough investigation, I discovered that the micrometer’s anvil and spindle were slightly misaligned. This subtle misalignment caused significant error in the measurements, particularly for the thin gear teeth. Instead of immediately adjusting the manufacturing process, we first recalibrated the micrometer. We then used a CMM to verify the measurements and found that the gear tooth thickness was consistently within tolerances, thus confirming the initial manufacturing process was in fact not at fault.

This experience highlighted the importance of verifying the accuracy of measurement instruments before drawing conclusions about a process. It emphasized the necessity of a systematic approach to troubleshooting measurement discrepancies and the value of having multiple measurement methods available to ensure accuracy and reliability. The project’s success relied on identifying this seemingly insignificant error in the measurement tool.

Key Topics to Learn for Use of Measuring Tools Interview

- Understanding Measurement Systems: Mastering both metric (SI) and imperial systems, including unit conversions and their practical applications in various scenarios.

- Precision and Accuracy: Differentiating between precision and accuracy, understanding sources of error, and applying appropriate techniques to minimize measurement uncertainty.

- Common Measuring Tools: Gaining hands-on experience and theoretical knowledge of various tools like calipers, micrometers, rulers, tape measures, levels, and dial indicators. Understand their limitations and appropriate applications.

- Practical Applications: Relating the use of measuring tools to real-world scenarios such as quality control, manufacturing processes, construction, engineering, and design projects. Be prepared to discuss specific examples.

- Data Recording and Interpretation: Understanding proper techniques for recording measurements, identifying trends, and interpreting data to make informed decisions. This includes understanding significant figures and error analysis.

- Troubleshooting and Problem-Solving: Be prepared to discuss how to identify and troubleshoot issues related to faulty tools, incorrect measurement techniques, and inaccurate readings. Demonstrate problem-solving skills in a measurement context.

- Safety Procedures: Understanding and adhering to all safety protocols when using measuring tools. This includes proper handling, storage, and maintenance.

Next Steps

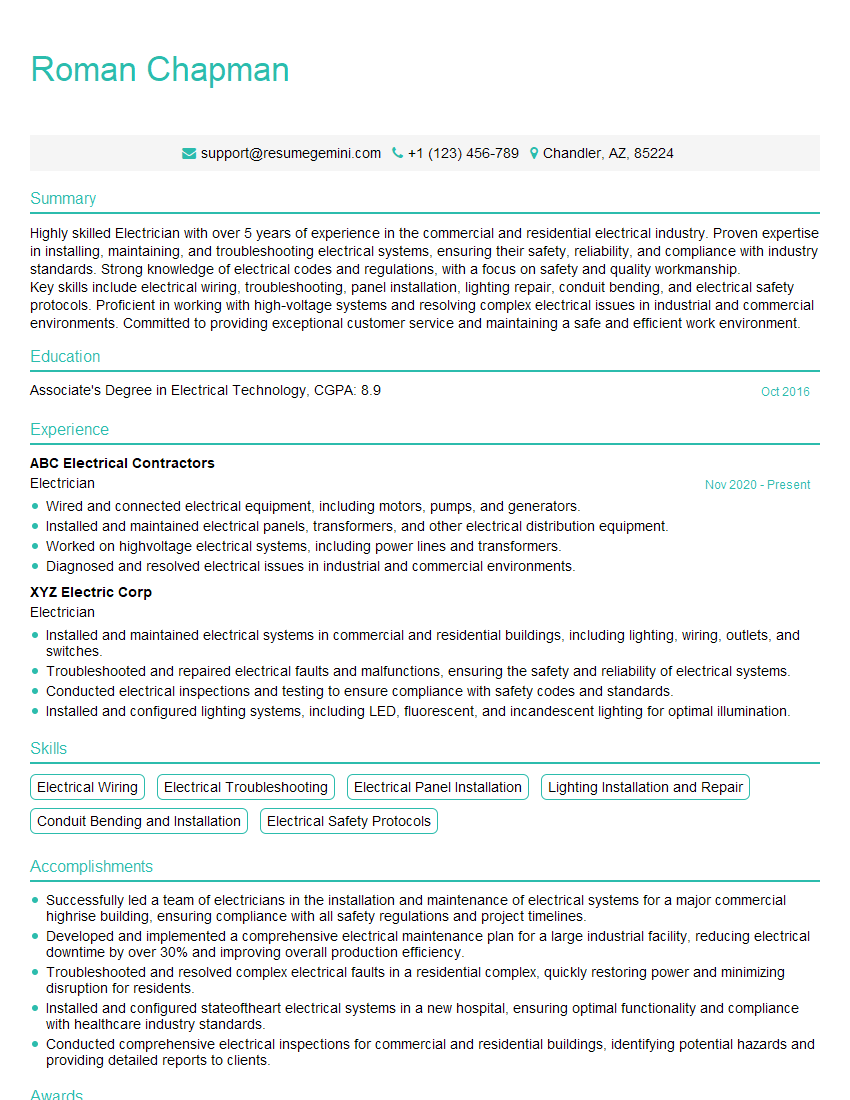

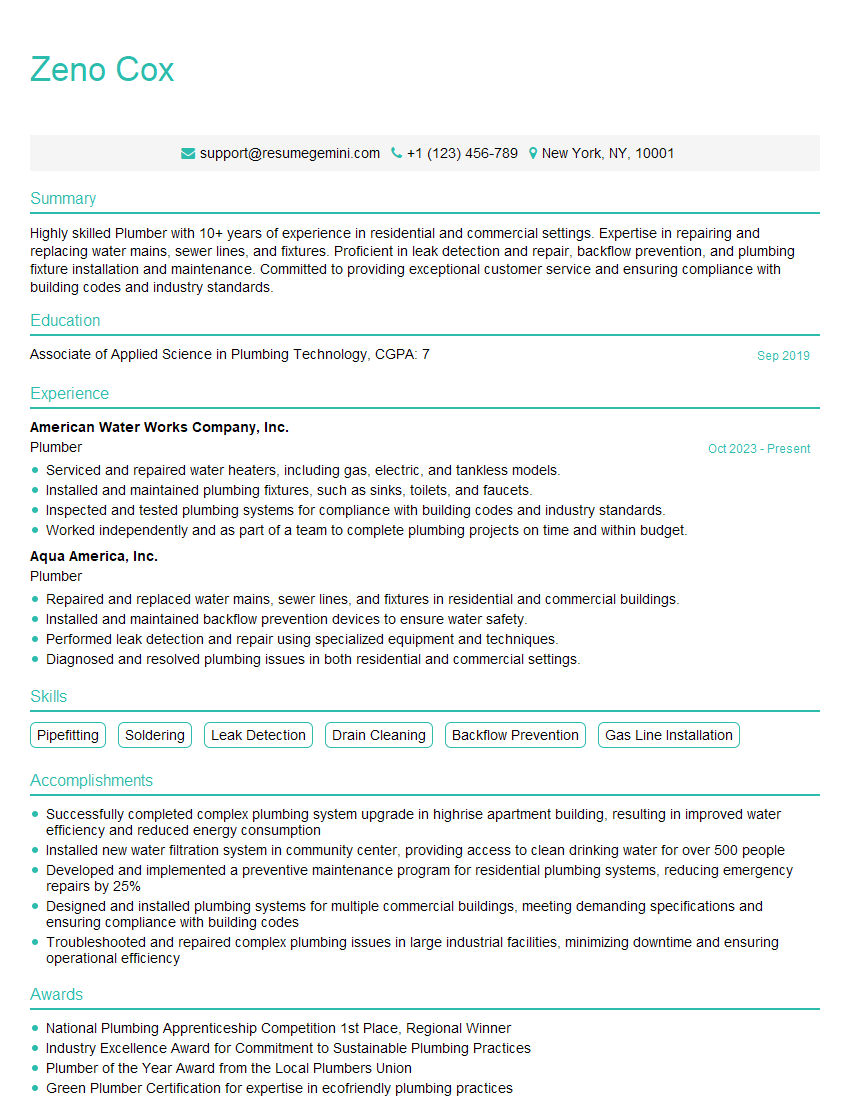

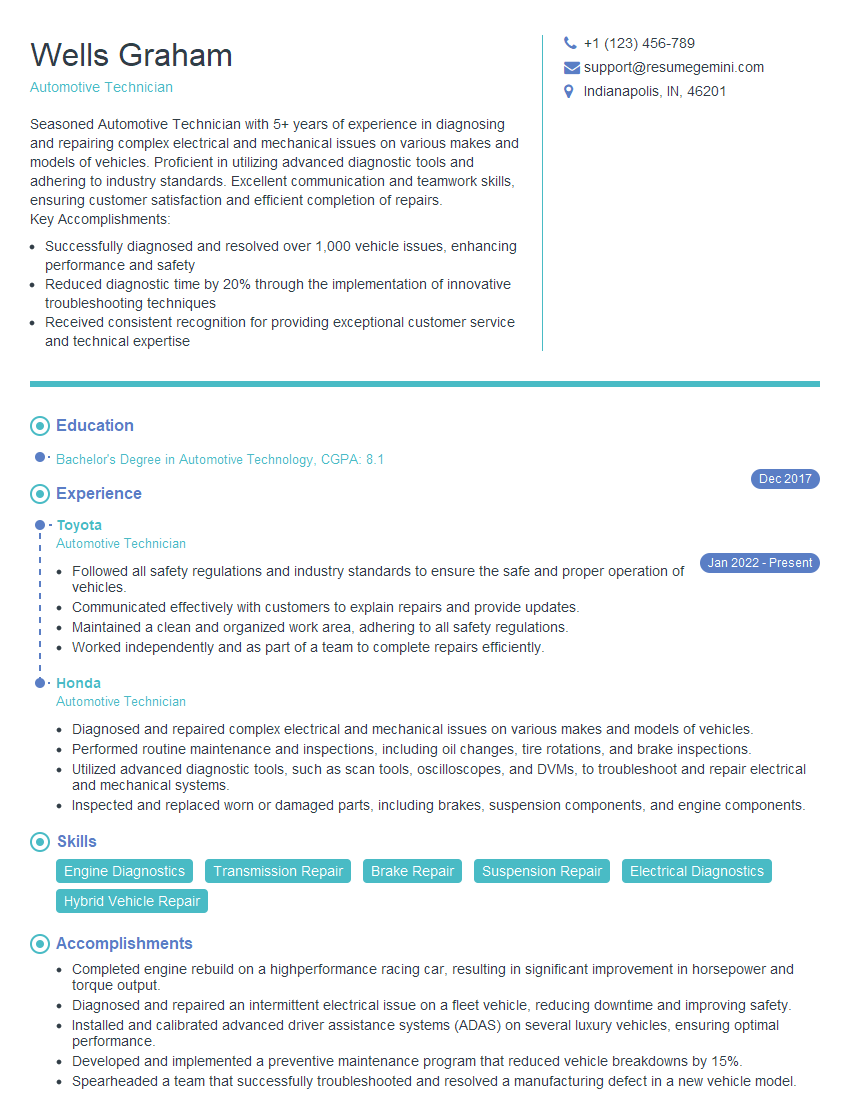

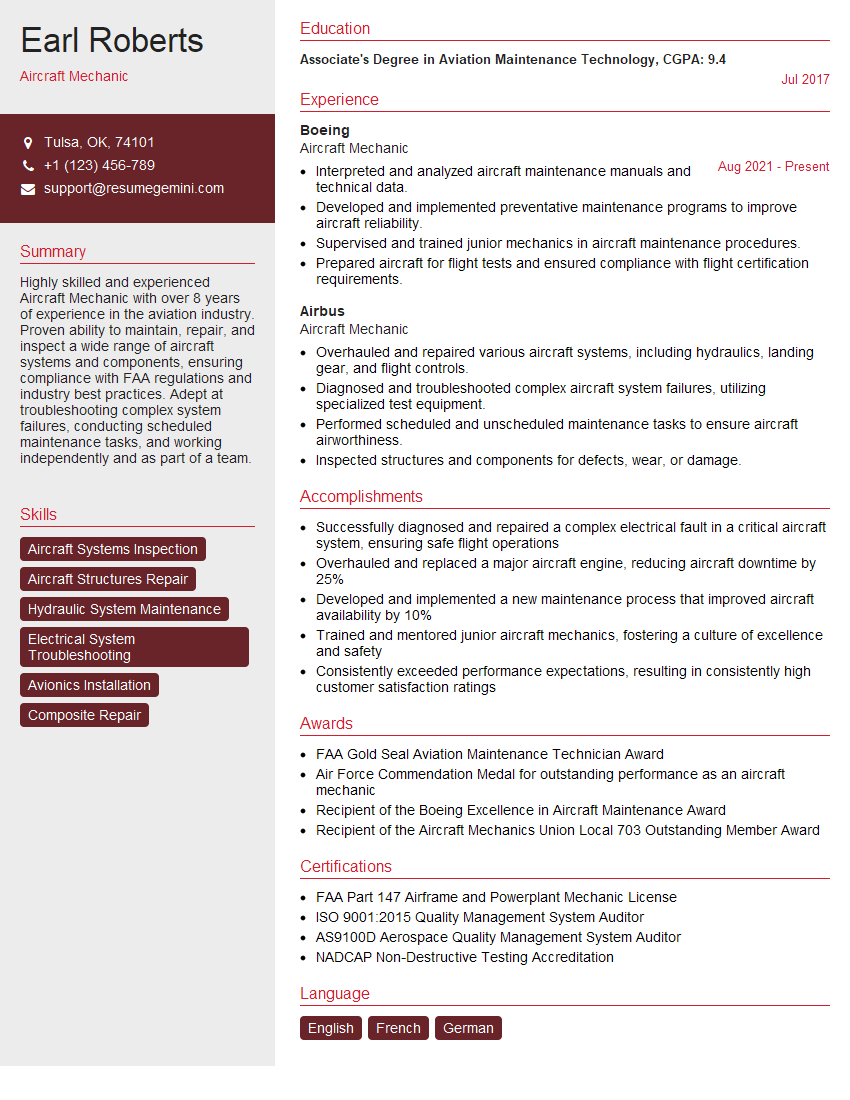

Mastering the use of measuring tools is crucial for success in many technical fields, opening doors to exciting career opportunities and higher earning potential. A well-crafted resume is your key to unlocking these opportunities. Building an ATS-friendly resume significantly increases your chances of getting noticed by recruiters. We highly recommend using ResumeGemini to create a professional and impactful resume that highlights your skills and experience in the use of measuring tools. ResumeGemini provides examples of resumes tailored to this specific field to help you craft the perfect application.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

I Redesigned Spongebob Squarepants and his main characters of my artwork.

https://www.deviantart.com/reimaginesponge/art/Redesigned-Spongebob-characters-1223583608

IT gave me an insight and words to use and be able to think of examples

Hi, I’m Jay, we have a few potential clients that are interested in your services, thought you might be a good fit. I’d love to talk about the details, when do you have time to talk?

Best,

Jay

Founder | CEO